The key to attacking a zone defense is understanding its purpose.

February 9, 2016 by Sean Myers in Opinion with 0 comments

If you’re new to competitive play and just got used to playing offense against person defense, a zone can frustrate you and make you feel like you’re back to square one. Basic offensive ideas and spaces that you’re just getting the hang of – like the force and break side of the field – are discarded. What were once intelligent cuts and wise throws are now a waste of time and energy, and often lead to turnovers.

Understanding the theory behind a zone defense is the first step to understanding how to play against it. Once you understand how zones are meant to work, you can see how certain zone schemes achieve their goals. From there, it just becomes a matter of exploiting their weaknesses, which takes repetition, practice, patience, and planning.

Zone Theory: Organized Poaching

If you’re familiar with playing against person defense, you understand what a poach is – it’s stepping away from your mark to provide help somewhere else.

Now, what if the defenders decided to completely disregard their marks, and instead came up with an incredibly efficient defensive scheme based entirely on poaching?

That defensive scheme is the zone.

By ignoring person-to-person matchups and instead focusing on a mixture of plugging throwing lanes close to the disc and occupying space further away from it, zones change, at a basic level, how offenses can work. This creates confusion, as the offense needs time to understand what they’re now up against and then adapt to it. The overarching goal of zones is to capitalize on that confusion, force a turnover, and get a break.

Two Basic Zone Schemes: Cups and Walls

There are two basic zone forms: Cup-based zones, and wall-based zones.

Cup-based zones put several players immediately surrounding the disc to plug throwing lanes as close to the source of the throw as possible. This is the cup. It puts pressure on the offense by making throwers feel suffocated, and making them throw numerous short, lateral, or even backwards throws to get anywhere. It can also create lots of turnovers by forcing the disc to a sideline and then trapping it there, or by pushing the offense into a high risk throw, like the one at the end of this clip:

The trade off of a cup-based zone is that there are so many defenders playing in the cup that, once the offense has bypassed the cup, there are very few defenders remaining to slow down the offensive flow enough to allow the cup to reset around the disc. The next layer of the defense is typically arranged in a wall, between 5 and 10 yards downfield. However, because there are so many players committed in the cup, there are too few players to effectively patrol the width of the field in the wall. As a result, the function of the wall in a cup-based zone is to contain the offense, and attempt to prevent too many upfield throws once the cup has been breached.

Wall-based zones scrap the cup in order to strengthen the wall. They tend to rely on a single mark — or sometime two — on the thrower, keeping most of their defenders five or more yards away from the disc. As a result, the offense is under less immediate suffocating pressure, but is also unlikely to find any offensive flow after a completion because so many of the defenders are downfield.

The Madison Radicals utilize a wall zone to great effect, in part because they can take advantage of the AUDL’s rules allowing for double teams. Nevertheless, their disciplined wall zone makes it nearly impossible to create continuation cuts and upfield flow, resulting in frustrated offenses that try to force an unwise throw.

Cup-based zones are far more common than wall-based ones, especially in league play, where newer players will likely encounter zone defenses for the first time. Therefore, newer players should first focus on learning how to beat cup-based zones.

Three Ways to Breach a Cup

The main obstacle posed by a cup zone is the cup itself. When the disc is inside the cup, there are few easy throwing lanes available. Once the disc gets outside the cup, however, the offense has a huge advantage, as there aren’t many defenders left to beat until the cup resets. How to effectively breach the cup, then, is the first goal for the offense.

There are three ways to beat the cup: Send the disc over the cup, through the cup, or around the cup. Going over the cup requires skilled over-the-top throwers and relatively good weather conditions. Going through the cup requires top-notch zone handlers who can manipulate defenders with fakes and misdirections. Going around the cup takes quick disc movement, but is relatively low-risk, and doesn’t require elite handlers, if done well.

Send the Disc Over the Cup

Hammers or scoobers are some of the best ways to get the disc out of the cup – it puts strain on the middle of the wall defenders in a cup-based zone, as they only cover a small amount of space in the amount of time it takes for a scoober to reach its target.

However, windy or especially wet conditions wreak havoc on the over-the-top game, and teams using a cup defense know this. This is why cups are used much more frequently in inclement weather.

Because offenses should not rely on good weather conditions to beat a cup defense, they should also be adept at shredding zones without resorting to over-the-top throws.

Send the Disc Through the Cup

Because the cutters are behind them, defenders in the cup have only a limited idea of where all the receivers are, and often rely on the thrower’s actions to predict where the threat is. Experienced handlers exploit this fact, and use fakes and other misdirections to move cup defenders out of throwing lanes and open up their receivers. Inside cutters – the poppers – need to position themselves outside the cup to be there when the thrower opens a lane up, and then turn and quickly create offensive flow after the catch.

Another way for a good, experienced thrower to go through the cup is to attack the mark. However, in most cups the mark is set at something closer to 90 degrees than the usual 45. As a result, breaking the mark often opens up nothing more than a swing pass, rather than any upfield gain. Therefore, breaking the mark in a cup defense is more like a risky way of going around the cup, than going through it.

Throwing through the cup can be risky: it ends up being a mind game between the thrower and the cup defenders. If a cup defender manages to bait the handler into making a throw that they’re expecting, the result is an almost certain turnover. Additionally, handlers and their poppers need to be on the same page – in order not to telegraph their intentions too much, the handler can’t directly communicate with the cutters like they normally do. Poppers need to understand where the handler is looking to throw, without the usual obvious clues. Any miscommunication is likely to end in a turnover.

Send the Disc Around the Cup

Often, one of the goals of a cup is to trap the offense on the sideline. Once the disc is on the line and the cup resets around it, there are even fewer throwing lanes for the cup defenders to cover, suffocating the thrower, and pressuring the offense into a throw they don’t want to take.

However, if the offense can send the disc to the sideline and then quickly bounce it upfield before the cup can reset, then they’re behind the core of the defense, and can build the flow that destroys a zone. This can only happen if the offense moves quickly and is set up precisely to facilitate this kind of movement, however.

All three teams in this video — Steamboat, Mesteno, and Santa Maria — are adept at swinging the disc around the cup, and at collectively moving the disc back to the middle of the field, once the cup has trapped the disc on the line. However, they have varying levels of success continuing upfield once they have bounced the disc around the cup to the outside. At times, as seen below, the lack of an effective continuation cut is clear, from the frustration shown by #4 of Santa Maria and from the swath of upfield real estate in the background left unthreatened by the offense:

Use Positioning to Create Offensive Flow

Any time the disc breaches the cup, the offense needs to be attacking, to prevent the cup from resetting. By planning ahead and setting up multiple continuation throws that strain a certain defender or area of the field, the offense can move the disc upfield quickly like a basketball fast break, pressing deep enough into the opponents territory to set up an end zone look, or force the defense to switch to person defense and create more confusion.

The best way to make sure that the disc moves quickly – without risky throws or shoddy communication that can lead to turnovers – is to try to plan for and set up at least the first three or four throws.

Here’s an example of what that can look like.

The Feature Play

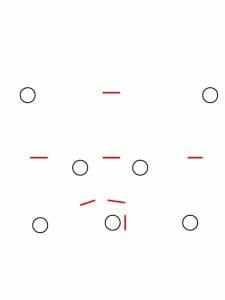

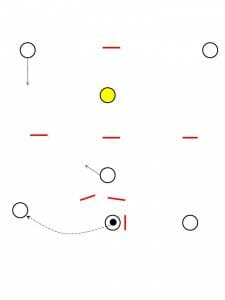

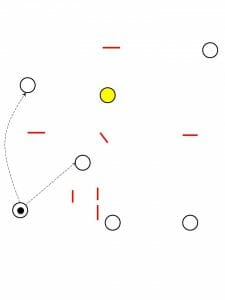

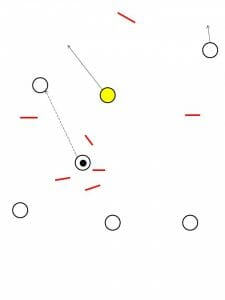

The Feature play starts with a crisp swing pass into the force side. As the disc is in the air, the deep cutter on the force side starts moving in. Simultaneously, the shorter popper – the “feature” – cuts toward the force side.

The force side wing defender now has to choose who to cover – they can move towards the middle of the field and take the feature, or maintain their position outside where they make it more difficult to hit the deeper cutter. If the feature’s cut is timed correctly, neither the middle of the wall nor the cup will be able to cover the open lane in time. If timed poorly, the middle defender will cover the feature, leaving open the more difficult over-the-top throw to the continuation cutter, in yellow. If the swing pass is good, the force side handler should have a 2-3 second window to receive the throw, make a decision, and bounce it upfield.

What most commonly happens is the force side wing defender doesn’t move – protecting the more threatening throw to the deep cutter. The pass goes to the feature instead, who should be able to catch on the run and quickly throw to the deep cutter on the sideline, behind the force side wing defender. The deep cutter can then turn and take an open look to the continuation cutter, in yellow, cutting upfield.

With the break side deep cutter occupying the deep defender, the feature, continuation, and force side deep can execute a three-player ladder up the field.

Conclusion

Zone defense drastically changes how an offense works. However, they rely on organized poaching, leaving most zone schemes vulnerable to quick disc movement, if the offense is organized and moves with a purpose. Cup-based zones, in particular, are easily shredded once the offense has managed to breach the cup, if the offense attacks the remaining upfield defenders efficiently.