With thanks to helpful comments from Adam Goff, Miranda (Roth) Knowles, Joshua Greenough, Heidi-Marie (Clemens) Wiggins, and Tyler Kinley, as well as a note of gratitude to the hundreds of players from whom we’ve stolen ideas and been inspired over the years.

Here is a scenario I’ve seen and heard reported countless times in the past two decades:

“We were playing a team we can beat. We were right with them early in the game, and both our O and our D looked good. We had a small lead right at halftime, but then in the second half we made some dumb mistakes. Our D gave us plenty of chances but we couldn’t convert and we had some unlucky drops and they caught a couple of lucky ones, so we lost by two. We just need to play a little crisper and harder next game. Oh, and it was kinda windy, too. We’ll beat them in normal weather…”

If you’ve felt like this after a game of ultimate, then you are not alone. We’ve all been there. We conceptualize ultimate as a game of skill and speed, and our mistakes are things that happen in the instant while an opponent’s successes are similarly rolls of the die.

We are wrong.

Here is that same game, reported from the other team of less talented but more experienced players in the wind:

“The wind was variable, so obviously we wanted to use it to our advantage since they are more athletic and probably better throwers in calm weather than we are. We tried several Ds in the first half, and some of them got shredded. Once we learned who their best players were, we shifted strategies to take away their best stuff in the second half. This forced their less-skilled players to make more plays in unfamiliar positions, especially with forces that called for throws and cuts that played against the wind. Predictably, they gave us a few drops. We made sure to get the disc in good positions so that the wind helped us, and we played heads up ultimate to keep plays alive when the disc was blown to the downwind side. They crumbled, like they always do when there is wind. Good thing Sectionals and Regionals are on windy fields in Oceanville.”

Ultimate is not a game that unfortunately sometimes happens in bad weather. Ultimate is fundamentally a game in which teams match up their talents and often succeed by using the conditions better than their opponent; it is occasionally punctuated by unusual examples of low-wind, perfect-conditions play in which the two teams have only their talents and execution to match. Ultimate is less like basketball, chess, or Legend of Zelda and is more like naval warfare, football, and Settlers of Catan in that the environmental conditions (including human conditions like attitude) change the playing field. If you want to win in ultimate, eventually you are going to need to understand and use the wind.

Interestingly, playing in the wind is seldom taught early, thoroughly, or well to young players. This is for a combination of reasons, including:

- Many players fall in love with the game in those rare perfect-weather situations

- Learning ultimate in the wind is complex and difficult to teach

- It is far easier to express “always do this” than to express conditional tendencies for variable situations

- The weather rarely cooperates, so it is more difficult to practice plan for coaches until we have a viable field-sized wind tunnel to use (compounded because of the associated likelihood of canceling practice in related dangerous or field-damaging conditions)

- Basic throwing skills are a mental stopping point for many players; once we emotionally worry about our throws fluttering, we stop learning about the rest of the game

- Younger players are often tasked with simple or redundant jobs in the wind so that older players can do the fun and complex decision-making jobs like throwing and poaching

Instead of learning comprehensively, the vast majority of ultimate players learn windplay through experience. Being on different teams with different levels of experienced players in different levels against different opponents will eventually give you a library of questions to ask and tactics to use depending on the situation. By your sixth full year of ultimate, you’ll have picked up much of it intuitively if you’ve had diverse experiences and you’ve been paying attention.

The purpose of this set of articles is to help a few people to shorten the learning curve of windplay. If this helps you to enjoy the game more, great! However, you should probably stop reading now if:

- You don’t learn well from long, poorly-written tomes

- You don’t believe that the authors are a good source for this information

- You are the kind of learner that needs to feel the wind in order to visualize it

- You have a better resource somewhere else

Ultimate is not a game that unfortunately sometimes happens in bad weather. Ultimate is fundamentally a game in which teams match up their talents and often succeed by using the conditions better than their opponent.

If you are still interested, then I will try to lay out the basics of windplay over the next five days. I’ll discuss general features of throwing and catching in the wind, and then go into tactics and strategies involved in three main scenarios: offense moving against the wind, offense moving with the wind, and playing in a crosswind. Last, I’ll discuss what you can do differently in endzone situations and extremely windy games.

I do have a few important caveats here. This is an incomplete work based on my experiences: there is no single right way to play the game, but I hope putting this together in one place is helpful. Instead, I simply want to get everything I’ve learned onto paper and let other people do with it what they find useful. I’ve been lucky enough to play with and steal from a huge number of players and teams, so virtually none of this is my own creative original thought. I am not going to include every detail; there is simply too much to include it all, so I am going to hit the important points while balancing size and depth here. I am also trying to balance and speak to new players as well as experienced players; it is likely that much in here will be either too obvious or too complicated for you, depending on you as a player. I’m using the US system of measurements because I am lazy and uneducated, but I hope this advice works equally well in the sane metric world. Most importantly, no player will become better just by reading these articles. I leave it to you to extract value for yourself by applying this in game situations of all kinds and finding out for yourself what works with your teams, your opponents, and your hands. Let’s get started.

Throwing And Catching

How much wind is windy?

I wish that I could lay out a set of guidelines for how many mph of wind makes a game officially windy, but those guidelines would be worthless. In some games, 7mph is crippling to normal offense. In high-level play, teams rarely shift strategies under 10mph. While 30mph is extreme for all players, the nuances of windplay mean that I can’t simply quote numbers to you.

How soon can you tell? Can you look at any two teams warming up for 90 seconds each and judge the wind instantly? Many high-level players can. A few players can read wind changes without feeling them (by noticing the differences in trees and other signs in the direction of the wind) at a pace that can allow them to wait for the best moment within a single stall count to throw. This ability can help in games with rapidly changing conditions, but it is often just showing off. Your goal should be to make reasonable judgment on the wind for yourself and your team within 10 throws on the game field. For most of us, this is absolutely sufficient to help with strategy, but not consistently achievable until at least 3-4 years of playing.

The field site will greatly impact the wind. Tree and building cover not only block some wind directions but funnel others to greater strength. Low structures and nature will block person-height wind but leave a shelf of higher, faster-moving air to disrupt hammers and pulls. Stadium structure can cause strong wind effects in different parts of the field, like the wind-tunnel sideline on the south side of the Windmill Windup final field or the crosswind that blows through the west endzone only of the Irving finals location. Wet conditions exacerbate the wind impacts, while warm wind is generally easier to deal with for offenses. Some local knowledge is always helpful; the fields in Santa Cruz give experienced players a chance to win the flip for wind in both halves around the midday changeover from sea breeze to land breeze. If you are heading to play in new conditions, following wind meters, webcams and surfing guides beforehand can give you a sense for it. It’s not uncommon for teams to start following weather patterns in locations of major international tournaments 12 months in advance to get a sense for the wind in those locations at that time of the year. Ask the Dragons of Boracay about their even more consistent and interesting example of seasonal wind effects on their specifically shaped island.

For the purposes of this writing, I’ll be separating wind into a few categories:

- No wind: There is so little wind impact that all throwers are unaffected.

- Thrower’s wind: There is enough wind to impact weaker throwers on the field, but the best few throwers in the game are not bothered or can gain small advantages (like increasing controlled distance downwind or gaining touch upwind).

- Normal wind: There is an easily recognizable strength and direction of the wind, and some parts of the field are currently more or less difficult to throw from. Note that normal wind is not zero!

- Strong wind: There is an obvious hierarchy to all parts of the field based on from where the disc is being thrown. Some reasonable ultimate throws are turnovers solely because of the wind.

- Extreme wind: A number of normal ultimate throws are now impossible to make reliably, and throws are commonly turned over because of the wind.

Using these definitions, I will move forward. Are you frustrated by the lack of numerical guidelines? Good. I hope this makes clear the complexity and the dependency of windplay on a large number of conditions that can’t be consistently recreated and which make every single game unique. If you want a simple game, go play chess.

Throwing In The Wind

WIND INTRODUCES COMPLEXITY to the flight of the disc. Your best bet in fighting wind is to make the flight path as simple as possible. You can do this by reducing flutter and shortening the flight path of the disc.

Flutter in the disc is often imparted by the throw itself. If you try to throw your absolute hardest, it is difficult to consistently control the movement of the soft, bendable disc at the same time. For throwing in the wind, you can reduce flutter by:

- Pulling the disc back with a relatively flatter angle to allow it to move through the swing of your arm in a simpler, flatter manner. You can practice this each day by stopping a few throws each day at the halfway point of the throw, examining your pullback, and adjusting to a disc path that requires less vertical motion. Another good way to think about this is keeping the disc in a single plane while throwing as a useful approximation to approach.

- Use your off hand to stabilize the disc while pivoting, pulling back, or throwing (longer on backhands, but still useful for many parts of pivoting motions with forehands and hammers). You can practice this especially against tight, physical, contact-rule-illegal marks in which relatively incidental contact can be rendered irrelevant with the off arm to help steady the disc and throwing arm. Note that any player will be more versatile if they can make throws both with and without the off hand on the disc.

- Keeping throws smooth such that the rear of the disc moves through the same space as the front of the disc already has moved through. This ‘shows’ less of the vulnerable large surface of the disc to the wind, allowing the disc to slip through the air rather than fight it. You can practice this by throwing to a partner who stands in front of a mirror or reflective window and looking to see if you can see the round of the disc as you throw. *1

While it seems unlikely at first, you can often achieve longer throws through smooth motions as compared to forceful throws. Obviously, the goal is to be able to do both.

Throws that rise or fall from any release point are necessarily longer flight paths and thus likely to be impacted more by wind. This is also true with throws that curve. Each additional inch of flight path is another opportunity to wind to impact the throw. To avoid this, successful players throw the shortest possible throw that is useful in a situation.

Sometimes, there is a balance to be struck between wind-risk and defender-risk. A typical swing pass is better if thrown farther out into space to allow the offensive player a good read and space to position themselves to seal out a defender. However, a tighter swing pass might reduce the wind risk by 10% while increasing the opportunity for a defensive block by 5%. Obviously, that is still a good decision.

Many players are taught to throw from low release points in the wind. This advice is an oversimplification: low throws that are flat are useful because they are flat and avoid longer flight paths. They also avoid wind impacts from slightly higher shelves of wind (like those that come off of sideline tents or over sideline teammates). Lastly, when you tell a young player to throw low you are also giving them an actionable focus point which can increase overall focus and, thus, success.

But throwing low often makes throwers slower, forces them to pivot generally further and thus lose quickness against the mark, and — most importantly in the wind — often creates releases that rise. On shorter throws, they are difficult to catch. These rising throws are difficult to control in the wind, are slow and laborious, and become habit-forming for young players. Focus on flat, not low, unless you are specifically working on avoiding shelves of wind or trying to go under a mark for some reason. Most players throw flat with strength, power, and the ability to pivot with balance if necessary when throwing between the knees and the belly button. Any additional lowering of the release point should be for a good reason and not just by dogma or habit.

Higher release points can be extremely stable or unstable in the wind, depending on the quality of the throwing motion. Is the disc moving simply forward without flutter? It will probably fly well at eight inches or eight feet off of the ground. High-release backhands are easier than forehands in the wind because it is more practical to stabilize the rear of the disc, even above shoulder level. For both throws, the tradeoff in quickness and stability is pronounced. Anyone can throw a neck-height forehand in normal wind, but the motion needed to throw it more quickly than a marker can react tends to make it less stable. This is especially true because marking hands generally move upwards faster than they move downwards, a consequence of our species’ past need to protect the head and neck more diligently than the feet and legs. If you have time, high-release throws can work. In tight situations, successful players buy themselves some of this time in situations where they might use a high-release throw in the wind by holding the disc in two hands at about armpit height, making the transition upwards take less time and create less flutter-causing motion.

And as a side note that every player since 2002 should know: Having an effective short off-hand backhand is a useful way to avoid throwing short forehands. Like the lefty layup, this is an easily learnable and useful skill for any age.

If you try to throw your absolute hardest, it is difficult to consistently control the movement of the soft, bendable disc at the same time.

When throwing upwind, discs tend to rise. Low throws tend to react to the wind by becoming more catchable, while high throws have a greater likelihood of rising out of a catchable range (or to a height that requires a receiver to decrease their relative speed compared to their defender, inviting blocks). Smart marks push upwind throws higher, and smart downfield defenders are watching high-release motions for opportunities to poach or pounce onto lofted throws.

When throwing downwind, discs tend to fall. High throws tend to become more catchable, while low throws are either instant turnovers or ankle-sniping hazards to an offense. This is especially true of faster break throws, and smart defenders try to make downwind throwers pivot and throw hard and low. All throws downwind are pushed to high speed, which narrows the effective catching window. When throwing to players moving away (either far for hucks or close for upline handler cuts) throwers should be aiming for the gut/chest of the receiver and less into space. Touch — best defined as the ratio of spin to speed for a particular throw — is more difficult in these situations. Since downwind adds speed but only marginally impacts spin, downwind throws have less touch and are less catchable by all receivers. This is exacerbated with harder discs like the Innova Pulsar used in the MLU; the gain in upwind throw-ability may be matched by the lead weight of a downwind shot which is more easily droppable.

Most throws in the winds aren’t directly with or against the wind, but rather at a cross-angle to the path of the air. In this large number of cases with a variety of winds and throws, the goal is to show less of the disc to the moving air. For example, imagine yourself on the forehand sideline with the wind in your face, coming towards and across your body from the throwing arm to the pivot foot. In a normal situation, you’d throw a flat forehand because it is the easiest throw to catch and the simplest to throw. If you were tightly pressured by a marker, you might angle the disc to curve from out of bounds back onto the field; in this case, you’d be trading a slightly higher risk of a drop to avoid a significantly higher risk of a handblock. The same might be true on a huck, where the power generated by a big windup might be worth the slightly less control of the direction of a blading huck (and the increased difficulty for the receiver to pinpoint a catching location before the defender does).

The problem is that raising the outside edge of the disc exposes that disc to the wind. It might be altered by small movements while still in your possession. It might be altered by larger movements once you release the disc. The wind impact overall will push the outside edge of the disc up and over the center, causing the disc to flutter. Depending on power in wind, this might result in anything from a quick turf to a long, curving turnover on the far side of the field. The solution is then to slightly lower the outside edge of the disc back to flat, which might be different than what you normally do in that position. Younger players tend to be overly worried about being blocked by the mark as well as less well-honed in bringing the disc back to a relatively flat position. For those players, they’ll tend to struggle with this forehand unless they can flatten and smooth the throw, even to the point of releasing the disc with the outside edge lower to correct for later wind impact. You can make a similar adjustment with just about every throw in the wind.

Catching

CATCHING IS JUST as important as throwing to successful windplay. Improvements can happen at both the individual and the team level.

For individual catching, there are concrete ways to improve.

Build in time to practice ‘flutterguts’-style catching of bobbled discs. The physical point is to improve coordination and quickness, but the mental goal is to be comfortable in odd situations where a falling disc is within reach. Players that pause in confusion about the new situation, or who react emotionally to the fact that they didn’t catch it the first time, will have a harder time reacting quickly and smoothly to the available disc. Players who have routinely seen the disc do this in practice time will do better.

For running cuts, don’t jump up. Many cutters jump while running as a way to stabilize the body from foot-pounding and simplify the catch, although it allows more time for defenders to make a play on the disc. In the wind, though, this strategy carries an additional cost as the disc is subject to the wind for a longer period of time. Keep moving forward or stop completely instead of taking the worst parts of both.

When catching, use your body to make a less-windy pocket of space. By positioning your body on the wind side of the catch, you can screen some of the wind. This is most effective in extremely windy situations, but can have some application at other times. This is most often done instinctively by stationary receivers making small adjustments while waiting for the disc. The alligator-style catch has the small advantage of slightly surrounding the disc. Additionally, a surrounded body style for windy catches will also constrict a dropped disc to a smaller area, making it easier to catch on a second attempt. Another way of saying this is to avoid catches with your arms away from your body and facing into the wind.

Learn to read the disc in the wind by doing longer distance throwing drills in windy situations. I’ve seen many coaches avoid throwing and catching drills, especially for long throws, because strong wind makes catches less likely. Unless you plan to eliminate long throws from your offense in wind (which I strongly recommend against!) you should be practicing these skills at least as much in wind situations. For coaches, try to de-prioritize effort — like ‘hard running’ and layout recovery catches after misreads — and emphasize early movements to predict and meet the disc. For older players, the goofy game ‘T-rex vs Pterodactyl’*2 was a way to decrease the size of the catching range, quietly forcing players to do more anticipation work.

From a mental standpoint: Try to be aware of how the stall counts impact the movement of receivers and not just what is happening in the thrower’s mind. At high stall counts, experienced players effectively exhibit some mental gravity towards either the reset hander or the downfield huck space as those throws become more likely.

When in doubt, over-read the wind. Imagine a right-handed forehand huck moving down the right sideline of a field. If the wind is blowing into the field from the right, then this disc is likely to move towards the middle of the field. If you can read it perfectly, do it. If not, then your choices are to:

- Read the disc for less curve. You’ll move relatively closer towards the sideline. If you are correct, great. If you are incorrect, then all other players will be able to attack in motion towards the disc, while you’ll be stuck underneath or need to jump backwards. You are at a disadvantage.

- Read the disc for more curve. You’ll move relatively farther from the sideline. If you are correct, great. If you are incorrect, then you’ll be able to adjust and move forward to the disc, sometimes able to make a play against a defender stuck underneath or jumping backwards. You’ll also have full vision of other players, allowing you to play their movements, move to seal them out without fouling, and avoid colliding with a teammate who might have a better chance at the catch.

Lastly, catch with both hands ready to be involved. You don’t have to clap catch everything, but the best players get their off-hand to a ready position even when catching with a single mitt. We tell our young players to ‘fight for the second hand’, because their natural tendency will be to focus only on the catching hand and to leave the other hand in running position (typically extended downwards in opposition). Countless discs each year are dropped by the intended hand but then caught by the partner hand. It sometimes escapes notice of all but the catcher themselves. Fight to keep this hand involved, and call your teammates out in practice when they let their bodies be lazy.

Team Strategy In Wind

FROM A TEAM perspective, your non-wind offense has more possible throws than does your wind offense. Trying to run the same cuts and movements will result in problems. There will be some cuts than cannot be thrown to, and good defenders will leave these targets to help elsewhere without risk. There are some places on the field that should be avoided in wind, and your offense should not put you there. Lastly, there are some cuts that require difficult catches and you will maximize those high-risk plays. For example, many teams run vertical stacks with large cuts from the back of the stack running towards the disc at high speed (and defenders in pursuit). This maximizes outstretched hand catching, which is disproportionately more difficult in the wind, and has other negative impacts that we’ll discuss later in this series.

If you are drawing up an offense or play that cannot be reliably completed at a game-winning efficiency in the wind, then you should be thinking of that as a specialty play for those few non-wind situations.

In all windplay scenarios, left-handed throwers give your team extra options. A single left-handed thrower might be able to throw long backhands when the rest of the team is confined to marked forehands. Even if this is not your main throwing threat, this adds possibilities that must be considered by defenders, and increasing the cognitive load for them is useful even if it isn’t explicitly used. Lefties don’t need to specifically play differently in any way to bring this benefit, and just like in baseball — where teams try to stack both their batting line-up and pitching rotation with a combination of lefties and righties — teams may prioritize a single left-handed handler over a slightly more talented right-handed handler on a team of righties. Equivalently, there may be left-handed cutters who are more effective in the handler position in windplay. Captains and coaches should not feel confined to positional limits that were built for a no-wind game.

You have the choice: Either run two different offenses, or adjust your single offense to rely less on cuts that work poorly in windplay. Remember, this is not a performance art. The wind is not ruining the game any more than thick grass is ruining the game. If you are drawing up an offense or play that cannot be reliably completed at a game-winning efficiency in the wind, then you should be thinking of that as a specialty play for those few non-wind situations. Note that a successful play doesn’t need to have a particular completion percentage in all wind, but the completion percentage in all conditions must be high enough that, when combined with your defense, allows you to score more than your opponent.

With this high-level overview complete, we’ll start to examine specific wind-game situations and the tactics and strategies that might fit best into them.

Points Where Offense Is Going Upwind

Obviously, the first and best way to combat strong wind is to cultivate a squad full of strong throwers and receivers, and to institute a reliable team offense that can function properly in less than ideal conditions. But there are also several strategic points to consider depending on the situation that will improve your team’s windplay beyond simply requiring skill improvements in your individual players.

In today’s installment, we’ll discuss the specific strategic elements that come into play on points where the offense is going into a strong wind.

Fielding The Pull

THE EASIEST YARDS on offense are typically available in the first throw of the point, as the defense is still chasing down on the pull. Especially when the offense is going upwind, defenses are likely to out-pull their coverage and give the offense an opportunity for 5-25 free yards. Depending on the strength of the wind, five yards can become increasingly difficult to earn the further up the field and later into the point you go, so be sure to get as much as you possibly can out of your first pass.

Depending on the strength of the wind, five yards can become increasingly difficult to earn the further up the field and later into the point you go, so be sure to get as much as you possibly can out of your first pass.

Using two pull-fielders can ensure that the fielder is not running so far that it impacts their first throw. In higher winds, they can act as a primary and backup against difficult rolling or blading pulls. Defenses often have a single player running hard to cover, so having three handlers involved in the initial throw may give more easy, profitable options than the defense can cover. A combination of two short throws between the handlers may advance the disc farther than a single throw more limited by the wind. While this can sometimes throw off the timing of the initiating cutter against man coverage, the additional yards gained and the opportunity to keep the disc in your handlers’ possession for another throw potentially make up for the momentary interruption; offensive flow into the wind is difficult to sustain anyway.

Certain set pull plays may be more difficult to run with fewer offensive players downfield, but in general the offense will gain an advantage by having fewer players in more space, provided that the handlers can advance the disc past the initial wave of defenders. Having three handlers back to start may also save time, as the defense is more likely to try a zone or other scheme for which those handlers would be spread along the back (instead of in a formation) anyway.

The easiest way to move the disc against the wind is to move it without throwing it. Yards after the catch (YAC) are a way to advance the disc at the end of high-speed cuts towards the upwind endzone.*3 Because of this, comeback cuts are less effective in the wind as they yield negative YAC, while handler dishy cuts or sweeping sideways cuts can be significantly more valuable when the YAC are factored into the total distance of the throw. Handlers on the break side should be looking for lateral passes after upfield breakside throws: this can turn a lateral pass into positive YAC as well as putting the disc in the hands of a better thrower with vision of the field and a mark struggling to regain defensive position. Note that offenses can be more efficient just by eliminating the large negative YAC of direct lane-running cuts as well as using this to advance the disc.

There are good reasons in many situations to throw passes that don’t necessarily advance toward the endzone. Generally, this is because they keep possession. Against the wind, though, sideways and backwards throws significantly increase the total risk that will need to happen in the point. Because fewer upfield throws are likely to be open, this effect is disproportionately large in upwind zone points where more backfield resets are thrown.

Handlers can stop losing ground by starting handler moves farther upfield, being more likely to make upfield cuts into the wind, and by prioritizing upfield break throws over ‘safer’ backfield resets. Against zone defenses in the wind, there is even less reason to move the disc backwards unless you are very likely to move the disc easily to a position for an even longer upfield throw. We’ve seen examples at recent College Championship tournaments where 3-handler zone offense sets systematically move backwards against zone fronts. Dump-and-swing can be a machine for ensuring that the defense gets the shortest possible offensive possession when you inevitably turn the disc over. Teams can stop this loss by resetting to handlers moving upfield more often — especially by crashing in and through the cup — and making use of their appropriate YAC. In order to effectively apply this principle, handlers should expect and warm up for throws coming at them from short distance, with a bit more speed, and under the duress of some physical contact more than they would see in a no-wind situation.

Hucking Upwind

PERHAPS MORE IMPORTANT than handler movement, upwind offenses must cut for, look at, and attempt long throws. While obviously a hindrance to completion percentage, the wind actually decreases the opportunity cost of a single long turnover. In other words, this isn’t no-wind where you’d be giving up prime offense for a single glory shot, but rather an attempt to score a valuable long gain when the alternative is a larger number of more-difficult-than-normal passes.*4

Cutters contribute to the choking effect on offenses by failing to cut deep. By saving their personal energy, they are taking away the offensive threat. This guarantees that there are no easy single-throw goals, but it also allows perceptive defenders to poach and help against other players. Worse, it changes a team with two deep cutters and two under-cutters into a team with four under-cutters. There isn’t enough space for all of those cuts, and players will be wasting position or even placing their defenders in closer free help situations.

On the other hand, teams that attack deep when possible against the wind give themselves shots at the upwind endzone. They also have the advantage of being able to catch wayward discs as upwind hucks float to strange places. Crucially, their turnovers will be in the best possible positions on the field. Thrower-led offenses often find the touch throws needed to initiate a cut are easier into the wind as well. Many upwind goals proceed in a “field → huck → turnover → quick turn → endzone O” pattern against D-teams that aren’t ready to be aggressive on their own.

For throwers, the decision of ‘what is a good huck’ can vary drastically between wind levels. There are good hucks in strong wind that would be terrible decisions in a thrower’s wind. There are impetuous huck decisions in no wind that every player (regardless of throwing skill) should be taking in extreme wind.

It is impossible to plan for and drill all of these situations, so this is where good coaches and captains make adjustments during games. This obviously also includes zone offense: if your zone O does not have a way to score in three throws, then you resign yourself to long, difficult upwind battles when the defense brings deep defenders in closer to crowd the play. Keep in mind that the best adjustment might not be an announcement to the team but rather a reminder to a particular player that the odds favor taking the huck when they have it.

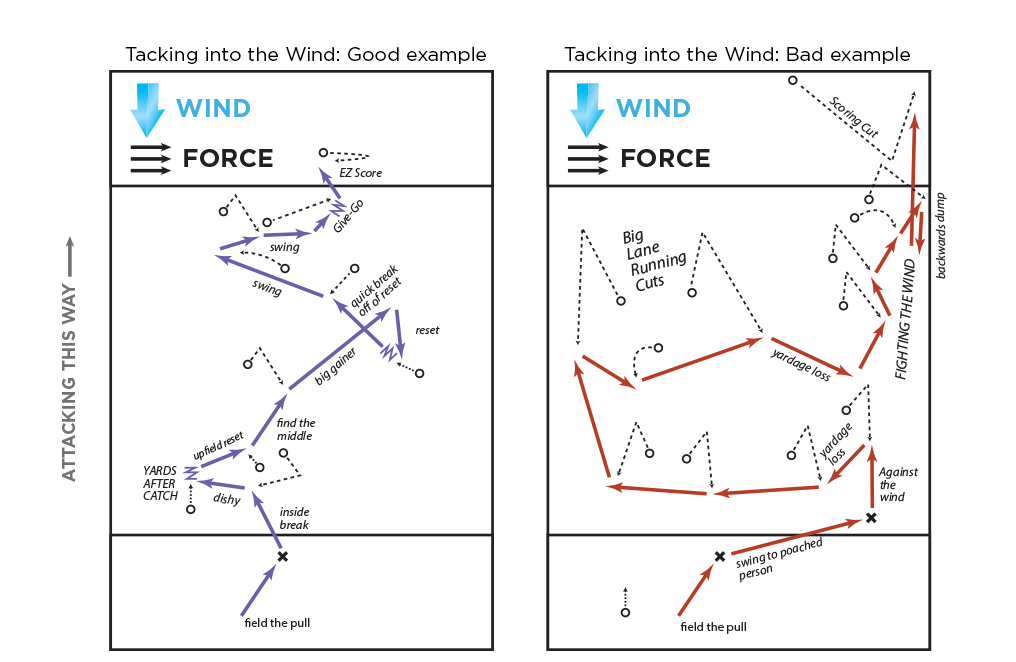

Tacking

THE STYLE OF upwind play that puts all of these pieces together is called ‘tacking’, inspired by the sailing maneuver of advancing upwind through a series of crosswind movements. Assuming the standard downwind force, teams should look to move the disc to the breakside (while losing as few yards as possible) to set up situations where the defense has to choose between allowing big throws or allowing easier, yardage gaining throws to the live side. The offense then tacks back to the force side, always looking for big throw or break throw opportunities.

In sailing, the plan is to move in a zig-zag. In windplay, the zig-zag is not intentional. Instead, this pattern of disc movement is a consequence of an offense taking available yards with the force and then occasionally finding opportunities to break or huck when the defense presents them.

Individual players can help this by moving the disc rapidly away from the force line, being aggressive with deep throws on the break side of the field, looking for dishy and YAC opportunities, and continuing to cut deep even for difficult throws.

For coaches, it is common and smart to put strong throwers onto an offense going upwind. Curvy, finesse throwers often struggle more than do gritty, powerful throwers. Additionally, care needs to be taken to keep some dedicated deep-cutters on the field at the risk of choking the offense. You can marginally deprioritize speed in upwind offense, since deep throws are less likely to outpace the cutter. Lastly, it can be helpful to ensure that you have height in your handler group. Because the defense may want to attack deep quickly after a turnover, those handlers will be responsible for more deep defense with less time to switch with taller cutters than in other situations.

Downwind Defense

DOWNWIND DEFENSIVE POINTS will often decide windy games. In strong or extreme wind situations, most points in the game will be scored going downwind.*5 After the rare upwind score, the new defense is almost expected to complete the break, with the opportunity to attack downwind; if they fail, they set the other team up to do the same.

This is an inherent problem in turn-based games and a special opportunity in wind-impacted turn-based games: ultimate is a unique environment in which you should look at your downwind D-points as absolute gold. Play your best lines going downwind and definitely your best defenders on downwind D. You will have some less-crucial upwind D-points in which to play other defenders if you need to balance playing time.

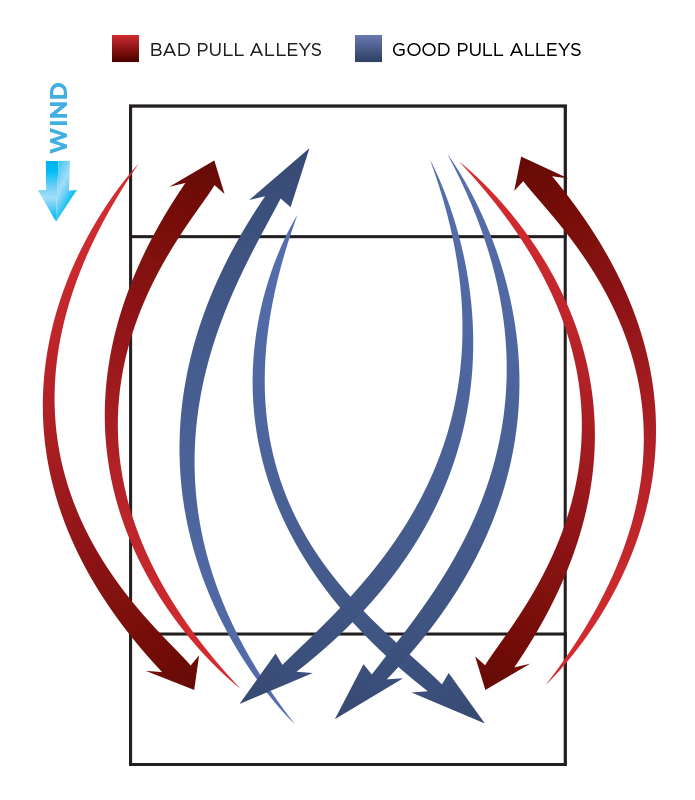

Pulling Downwind

WHEN PULLING DOWNWIND, you have all of the advantages. The best pulls downwind are point enders and put the offense in nearly unwinnable situations.

There are two lines of thinking on downwind pulls. Some teams focus on keeping the pull in-bounds, which — if the pull is fielded in the endzone — has the advantage of exposing the offense to the wind for the greatest amount of distance. A downwind pull out of bounds amounts to a 45-50 yard mistake, and it sets up the offense to put the disc in a fresh thrower’s hands for an organized attack. Under this line of reasoning, a puller who misses the field twice in ten attempts going downwind is far too much of a risk, even with a few incredible pulls mixed in as well.

The other line of thinking is that the defense can compound the advantage of wind with rest and time. For these teams, this is a chance to shoot for killer pulls in the back corner. As long as the puller doesn’t commit the unforgivable mistake of choosing a poor trajectory and pulling out of bounds — which might gift the other team a short upwind field — then the best the offense can hope for is a stationary thrower at the brick mark against a rested defensive team who has had time to see formations, get their matchups, and communicate.*6 For these teams, the short or fast inbounds pull is worse because it allows several uncontrolled passes and a more chaotic atmosphere.

How should your team choose between these options? The best balance likely depends on the risk:reward of your downwind puller and the ability of your defenders to usefully communicate at the start of a point. High, floaty, and in-bounds is excellent for deep pull coverage, but can be harder to control. Fast, bladey pulls that roll out the back of the endzone are excellent, as they ensure your rested defense is set up on an offense just outside of their own endzone.

Either way, it is crucial that the puller understand and utilize the appropriate pulling alleys to maximize the advantage provided by the wind and minimize the risk of a short, out-of-bounds pull that can result from a slight miscalculation or sudden lull in the conditions. As badass as a huge, looping pull to the back corner can look when it works, the opportunity cost is too high not to choose a safer flight path that stays between the sidelines and can still have a devastating effect when properly executed.

Downwind Defensive Team Strategies

YOUR DEFENSE SHOULD aim to funnel the disc into the hands of weaker throwers. Individual defenders can allow in-cuts to the force sideline, or teams can scheme to help in one place while allowing throws to those that struggle in the wind relative to their teammates.

Because you know that the opponent will be looking to maximize YAC, handler-defenders should focus on pushing handler cuts backwards. This is doubly effective because this reset often becomes a downwind throw which is difficult to complete with touch.

In higher wind, markers may want to accept curvier around throws while prioritizing stopping more high-yield hucks and inside breaks.

All markers should be cognizant of their angles. In low wind, the goal of the mark should be to persuade the offense that the reward in throwing to the force side has greater value than risking a block by trying to break the mark. This constricts the offense. In higher wind, markers may want to accept curvier around throws while prioritizing stopping more high-yield hucks and inside breaks.

Cutter defenders should be putting their effort into winning the middle of the field, as these cuts are more likely to lead to successful tacks. This can start right from the beginning of the play, as the first defenders running down towards the disc should run through the middle lanes and provide clutter for the first thrower to navigate before moving to their individual players or zone areas.

All defenders should be playing with their heads up. Windplay gives more opportunity for help onto floating discs or compressed cutters — there are more bobbled discs to snatch at. Sure, this means defenders will be watching their cutters less and allowing for more “surprise” poached cuts to space. However, increased wind means that more of these surprise cuts are unreachable by the disc anyway.

Coaches can encourage and increase this valuable field awareness by discussing heads-up play in practice or training with alternative-rule games — such as throwing a second disc onto the field randomly during scrimmages, the catching of which is worth a point while play continues.

In downwind D, teams can play more positionally-specific defenders. Your handler defenders can lock in, knowing that offensive handlers are less likely to leave the backfield in high wind to go gallivanting downfield for difficult, often curving long hucks like they might in no-wind. Cutter defenders can be smarter, slower, and tend to play closer to likely cutters, though the likelihood of upfield deep shots makes height and disc-reading marginally more valuable. Obviously, zones can be played with defenders who are even more positionally-specific.

When you force a turn, you should be relatively more aggressive than you would be in no-wind situations — especially after longer possessions. The relative ease of downwind offense, combined with the higher likelihood of short fields, means that you may need fewer handlers and throwers after the turn. Make sure to keep one effective hucker on the field at all times, though: any turnovers you force near the upwind endzone would be a shame to give back without taking a chance at a long, profitable turnover as compared to a short one. Especially in strong downwinds, D-team handlers should never accept a risky reset or stall when they can attempt a long throw. Long turnovers with a tired offense are a net gain in position from the start of the possession.

Defenses comprised of offense-focused players are more likely to use poaching and switching against a team moving downwind, so great cutters with rapid footwork and fakes often aren’t as useful as players who can recognize when they are being left and who can find open spaces in which to sit.

Remember, these downwind defensive points are gold and need to be treated as such. Take advantage of your pulls, operate intelligently with your defense, and then be prepared to attack aggressively off the turn so you don’t forfeit the advantages provided in playing downwind.

Points Where Offense Is Going Downwind

While few people may expect you to score all of your upwind offensive points, it is critical that you not get broken while attacking downwind. With the wind at your back, your offense has a privilege that must be used. Your goal is to use the wind better than your opponent’s offense, so it isn’t enough just to score more frequently than you would with no wind.

There are several ways to adjust a downwind offense in order to make scoring easier and, crucially, decrease the likelihood of short turnovers that can lead to easy, advantage-shifting goals into the upwind endzone.

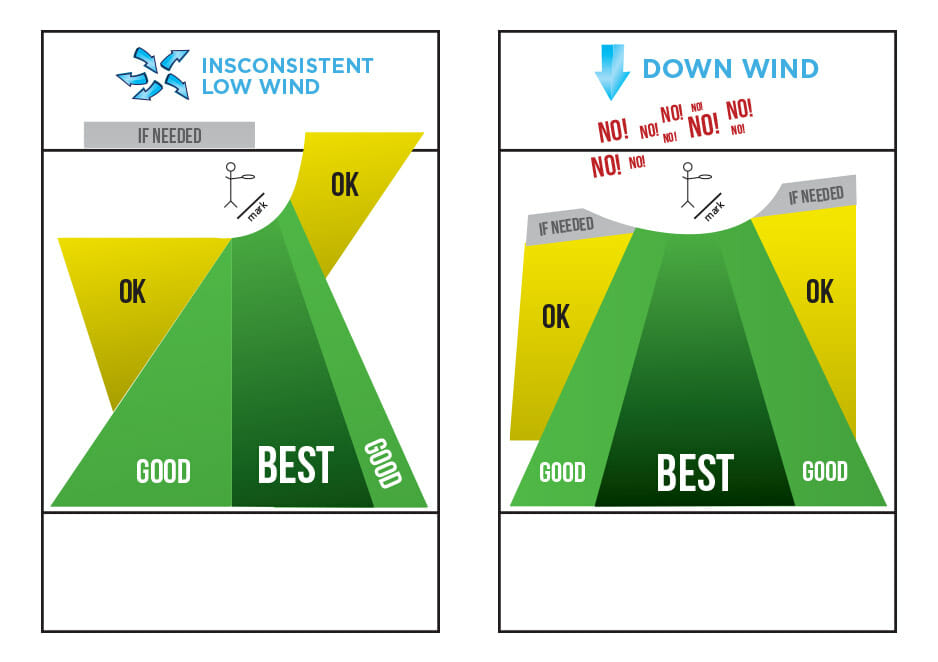

Setting Up The Offense

WHILE RECEIVING THE pull going downwind, players should remind each other to hustle to starting positions since the shorter, generally lower pulls that you see in these conditions will get to the offense more quickly. But just as with upwind offense, early yards can be the easiest available to you the whole point. Cluttered offensive players can make gaining these easy yards more difficult for the free handlers. Also, by hustling to position, more offensive players are likely to be ready to stop rolling pulls. It can be helpful to spread at least one player near each sideline in order to make sure that stoppable sideline rollers can be reached. On fields without natural barriers, there is a big difference between when a handler can pick up a stopped disc near the sideline immediately and when that handler has to chase down the roller two fields over and bring it back to a rested defense that has had time to get their matchups correct and plan against a formation. Spreading on the line helps to hide vertical or side stacks as well, which are often used for downwind pull plays.

More than any other moment in the game, downwind offense requires keeping the deep space clear.

As we talked about in Throwing and Catching, the hardest catches in the game to make are coming straight back to a disc while running at speed. Downwind offenses will do better to use more cuts that don’t fit this profile. Handlers can help by identifying a cutter early and throwing at their earliest open moment. The wind at your back should make this slightly longer throw easier anyway. This will help the cutter catch before they are at sprinting speed, will gain more yards, and often is better practice anyway to ensure that defenders don’t get a good chance to gauge the angle of the cut and throw.

More than any other moment in the game, downwind offense requires keeping the deep space clear. While the reachable hucking space is a bit farther away, any defender left in that space is stopping the biggest, scariest option. If you sit in the deep space, you effectively cancel out the downwind advantage by yourself. Deep cuts can continue a bit longer than usual since throws that go up late will still get there in a hurry, but should be followed quickly by something intelligent. This isn’t always a hard-charging clear back towards the disc. It could also be a sideways slide towards the open or breakside space so that handlers can see deep poaches and get you the disc to take advantage of them. The longer, higher throws that do this are aided by the downwind anyway.

The higher throws that are difficult are those that must find spaces between a closer and a farther defender. Because the wind will carry the disc, middle-depth throws over the top of a defense are more difficult when going downwind. Crossfield and diagonal looks are there, but be wary of trying to pop a hammer over the top of the middle of a zone and in front of the deep — the wind will tend to push the disc to one defender or another.

Handler Positioning Downwind

ONE OF THE primary responsibilities of handlers in downwind offense is to drive the disc down the field. This requires disciplined positioning and decision-making from the handler corps so as not to accept passive horizontal swing throws. These receivers may be open, but they are often catching the disc flat-footed. Worse, they often move the disc toward the sideline where the defense wants it to be in order to limit continuation options. It is incumbent on handlers who are standing open to have some instinct for why they are being left alone. Is it because the defense is terrified of your insane deep cuts? Probably not. Instead, you are open because they want you to be open. Respond to this by being open somewhere else.

For the sideline-positioned handler, you have a few options when left alone:

- Cut behind the disc for an easy backwards reset. Backwards resets become into-the-wind throws in downwind offense, so these short touchy throws are relatively easier than if they were downwind. If you do this well, you can use your space to get off continuation break throws without a mark. You can find copious examples of this in any video of Riot, especially near the endzone.

- Slide farther down the sideline to gain yardage. An open side swing pass is a relatively easy throw downwind and you can catch the disc without pressure relatively close to the cutters, enabling easier downfield throws. You frequently see Furious George do this well (so, naturally, I dislike this cut).

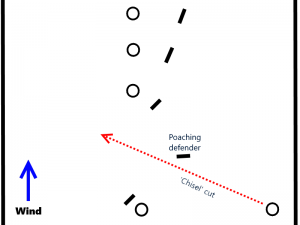

‘Chisel’ into the defense by cutting across in front of the thrower, past the poaching handler defender and into the upfield breakside space. This opens up opportunities for short gainers with position on the live side, short breaks leading to bigger breaks after passing in front of the handler, or more often opening up a huge space for easy and lucrative downfield throws when the handler defender is forced to leave. Smart teams may keep that first handler defender in place and help with a second handler defender, which will allow open break throws to unpressured handlers if you are smart about it.

‘Chisel’ into the defense by cutting across in front of the thrower, past the poaching handler defender and into the upfield breakside space. This opens up opportunities for short gainers with position on the live side, short breaks leading to bigger breaks after passing in front of the handler, or more often opening up a huge space for easy and lucrative downfield throws when the handler defender is forced to leave. Smart teams may keep that first handler defender in place and help with a second handler defender, which will allow open break throws to unpressured handlers if you are smart about it.

The key is not to accept a passive swing pass to a bad area of the field unless you are absolutely forced to do so. It might appear to be a smart and safe decision to keep the disc moving to an open teammate. It might even feel personally empowering to complete a relatively long open throw in the wind. But when your offense is going downwind, these swings are bad for the team. One of the best ways to gain the mental edge in a wind game is seeing your downwind offense score far more easily than your opponent’s downwind offense. And, simply put, teams that avoid positioning the disc on sideline the will score more easily.

This includes situations against zone defenses, where keeping the disc moving forward in the middle of the field will be steadily advantageous to avoid traps and wasted yardage. Experienced wings tend to position a few yards farther from the sideline on the first few throws against a zone to give extra options in case a trap is coming. The only difference between downwind and upwind zone offense, really, is that the get-out-of-trouble backwards throws are easier. Lastly, these sideways swing passes are inherently moving across the wind (and being pushed towards the defender). Any turnover on this pass becomes a fast break or short-field opportunity. The risk rises, but the reward decreases, for this often open swing pass in downwind O.

Personnel Decisions

FOR COACHES AND captains, downwind O is a time to consider using your players for whom wind-throwing is not a strength. They will often be able to reliably throw downwind or, at the least, throwing short backwards resets with the relative assistance of the wind in their face. Teams will often allow easy swings, which may also take pressure off. For that matter, downwind offense typically requires fewer throws anyway, so poor throwers/catchers might not even touch the disc. With this skill at less of a premium, you can play better cutters, defenders, and thinkers who might play less without the wind or in other types of windy situations.

It is imperative that all downwind O players be able to contribute to a reasonable defense. Turnovers in the wind will happen, and as we’ve discussed, some of them are more likely to occur while moving downwind. In windplay, the primary goal must be defending the upwind endzone. If you have a player around whom the defense collapses, then you put pressure on your team to be better and mistake-free on offense. Downwind offense is often best when loose and aggressive, so this combination of pressure and situation is even more problematic. On the flip side, your offense doesn’t need to be excellent if they are able to play defense at a consistently high level.*7

Building 7-person squads with which to score an upwind D point can be an exercise in makeshift engineering.

Who on your team can play upwind D-line? Everyone. If a player on your team has a strength, then there is a way to use that strength in upwind defensive points. Quality receivers are useful for cleaning up wayward passes. Throwers help when you get the disc. Defenders and athletes of all kinds are obviously great for defensive possessions and completing big shots at the upwind endzone. Lack of speed is less of a liability going upwind and the offense already has the wind advantage so their use of speed matchups may be less profitable (and may require them to produce long lane-running cuts from which you’ll get drops). Short defenders won’t be hung out to dry on deep cuts with the disc less likely to float downwind. Got a player with one great IO forehand or a powerful hammer? You can use that to start plays, since the risk/reward has changed compared to no-wind situations.

Building 7-person squads with which to score an upwind D point can be an exercise in makeshift engineering. I’ve been on teams that had great success with a team of five solid defenders, all of whom were passive and relatively unskilled on offense. The sixth player was a great deep target, and the seventh was a huge hucker with ultra-aggressive decision-making. The equation was simple: get the block, get it to the hucker as quickly as possible, and take a shot. This offense would have been a nightmare in no wind, but in strong and extreme winds, it lost little efficiency compared to the losses of normal offensive schemes. I’ve used zone or transition fronts with tall players guarding their shorter handlers, setting up quick gainers to height mismatches for easy yardage when backed. I’ve won games by building teams with tons of quickness but not much else, and piecemealing offense upwind with a barrage of handler cuts and no throws to the break side or even more than five yards at a time.

While it may feel like upwind D line offense is extremely limiting, the disadvantage of going into the wind actually expands the number of useful possible strategies; the goal is simply to be better than the opportunity cost of any single decision and not just better than the no-wind offense of the opponent.

Defensive Strategy

WHILE DOWNWIND OFFENSE has the help of their wind privilege, they also have all the pressure. Meanwhile, playing defense in this situation is about making smart decisions and insightful, opportunistic gambles in several situations.

When pulling upwind, search for options that work for you beyond simply gripping and ripping. If you can’t get an upwind pull to the brick, then you may find more success using rollers to reliably pin the other team in a sideline position. In other situations, pulling out of bounds may save your defenders some energy. This is especially true of wind strengths where reaching the brick is impossible; you have little to lose by allowing a downwind team to center the disc, and you give your team time to examine the offensive positioning and prepare.

In upwind defense, any pass that isn’t a big downwind gainer is a win, as it keeps the disc upfield and increases the number of throws that can result in a turnover. Typically, successful teams combine some amount of allowing lateral swings from the middle of the field with pressure when the disc is on the sideline. It is less important that you play in one particular style; your team should have some sense for the style you want to use, but captains and coaches can be on the lookout for strategies that seem to work well for you or poorly for your opponents.

To start, it is helpful to limit the best thrower on the other team. Luckily, most offenses announce who that is that by calling the pull fielders to throw one pass to this player in the middle of the field. Unless they are the very unusual team calling for someone other than a top thrower as the second touch, you know that you should stop the ‘2’ from effectively throwing downfield with their pre-arranged play. Poaching with the other handler defenders is typically the easiest way to do this, encouraging lateral swing passes to the off handlers near the sidelines that the defense wants anyway. Watch the Japanese women for good examples of this, and notice that the correct location for this defender is often a lot farther away from ‘their’ player than most of us feel comfortable being. Going halfway and not fully committing to the poach does exactly zero good, as it leaves both the upfield and swing options open. Get as far over as it takes to take away that upfield lane, and communicate with the mark so that you aren’t double-covering space and wasting effort.

There are many ways to increase the number of swings that a team has to throw, so this isn’t limited solely to handler defender help. Marks can and should flatten in the wind. Teams can throw zone when the offense is going downwind — tight zones that apply little pressure but prevent up-the-middle throws can be useful and give a great change of pace from constant person D.

In upwind defense, any pass that isn’t a big downwind gainer is a win, as it keeps the disc upfield and increases the number of throws that can result in a turnover.

After that first set, upwind D can also be a great time to increase the pressure on handlers. This can be done in person defense or in partial zones with extra defenders tracking individual handlers. Many offenses will look to relieve that pressure with strong upline handler cuts, but those throws can be more difficult with the wind at the thrower’s back. They are also more often dropped in tight spaces when touch is difficult to achieve. Any turnovers forced by handler pressure typically lead to shorter fields for the upwind team to move towards the endzone, which is a major advantage.

Downfield, you can use the wind to push slower players deep. Because the disc speeds up more in relation to the wind than will actual humans, it can be productive to force slower, taller players deep and watch the disc outpace them. True, these are turnovers requiring an entire field of offense, but this tendency might still shift how you play particular matchups. On an individual level, if you’ve guarded a player who missed a downwind layout on a huck in the same game you should remember that they are often less likely to cut for that same negative experience again. You can also help deep more often, since the cost of leaving a player near the back of the formation often results in them running towards the disc and the wind which leads to more drops. This is true even on mediocre switches in which the cutter gains an advantage that would be very dangerous in no wind.

Upwind D Line Offense

WHEN YOUR TEAM does get the disc, you should look to do the following things:

- Fast break. The quicker you can get the disc moving, the less likely it will be that you will need to manufacture disc movement against a rested, ready defense that has chosen their matchups.

- Be aggressive. The higher the wind, the more likely that a given open huck look should be taken. The opportunity cost is lower than in no wind situations, and there are more opportunities to catch bobbled or blocked discs.

- Treasure your short-field upwind opportunities. If you are close to the endzone, do whatever it takes to score, even if it means burning timeouts, playing through only your best players, playing only through the opponent’s weakest defenders, or calling plays that work well once but won’t work repeatedly against the same people. This upwind goal is worth the later loss, and there won’t be a more important time.

Lastly, if you do score your upwind point, consider loading the downwind D line with your best possible team to complete the set. Depending on conditions, it may even be worthwhile to burn a precious timeout to rest your top players for this double duty. By completing the set, you take full advantage of the wind you worked so well to acquire. If you fail to do this, you give the advantage back plus the chance for the opponent to complete their own.

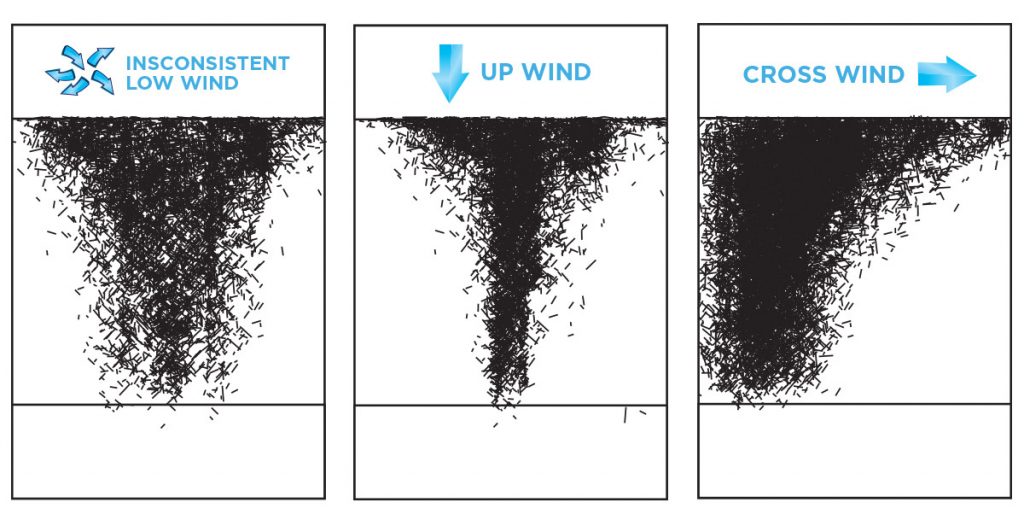

Playing In A Crosswind

If you’ve read this far, then I appreciate your effort already. It is likely that nothing in this section will be new to you, since the principles of windplay are really just an extension of throwing and catching in the wind. Likewise, the principles of crosswind success are really just a more interesting case of other windplay rules being combined.

For those calling lines, crosswinds are tough for players with only one good throw. If a player lacks a functional forehand or backhand then they are liable to be trapped into using that throw. This could be on the downwind sideline being forced to throw a poor throw downfield, or it could be a team that shifts the mark and poaches to force this player to attempt resets with their weaker throw against the wind. In any case, crosswind takes its toll on single-throw players and will make more versatile throwers marginally more valuable even without a single strength.

Crosswind Pulls

PULLERS ARE MOST effective by angling the disc to use the wind. For a right-handed backhand puller, a left to right wind is the easiest to use. Throwing with the far side of the disc level or slightly up will let the disc use the wind to gain speed, even if only in a lateral direction. You can pull on whatever angle is most likely to let the disc touch the field one time while gaining good distance. In thrower’s wind, you’ll decrease the likelihood of really large mistakes by pulling in an arc that is always on the field (for our right-handed backhander, this would be from the right side of the line) instead of spending a lot of time over out-of-bounds territory. If it curves incorrectly, it is still a reasonable half-distance pull.

In stronger wind, pulls that blade more become difficult to catch. This gives the puller the best possible chance to blade and roll the pull out the back or side of the endzone, requiring a slower walk-up and good field position similar to downwind pulling. In extreme crosswind, your goal is to put the other team on the sideline.

When receiving the pulls, it is again useful to have two players back to field before moving the disc to a single ‘2’*8 or ‘hitch’, just as was described in Part 2 for fielding pulls going upwind.

Once a pull is fielded, it is useful to head for the upwind side of the field immediately. This might be a single or a pair of throws, but instead of only gaining yards toward the attacking endzone, it is just as valuable to move the disc towards the opposite sideline (most crosswind pulls will land on the downwind side of the field). Many teams run crosswind pull plays with the ‘2’ positioned on the upwind side of the field. In a vertical stack this limits the offense to only a single lane but makes throwing (especially resets) far less difficult. In a horizontal stack, using the sideline handler as a ‘2’ eliminates some of the poaching opportunities because the defender is now having to decide between helping and giving up the valuable middle of the field. This offset ‘2’ can run most if not all of the same plays that you use in other wind.

Defensive Schemes

DEFENSIVELY, THE VAST majority of points will be spent forcing the thrower towards the downwind sideline. This lets the mark work with the aid of the wind, making some throws so difficult that they likely will not be attempted often. This constricts the offense and allows defenders to help each other more often, anticipate disc movement more accurately, and make mistakes without consequences.

Whatever the defensive scheme, the priority should be to force or allow throws to the downwind sideline. Some zones achieve this by luring the defense in with free yardage only to then clamp on a strong trapping cup. Person defenses do this by helping off of downwind players frequently, especially at the start of a possession to stymie the best thrower. Downfield defenders can offer additional help to the downwind side, as players on the upwind side might be valuable targets but are less likely to be throwable.

One team or another is setting a trap: either the offense is trapping an overzealous defender in a useless position, or the defense is trapping the disc into a wind-pinned open throw.

The most common manifestation of this is when guarding the downwind handler in a horizontal stack. All else being equal, this player should virtually never be guarded closely. That defender is free to help in other areas of the field, since throws directly to his player are beneficial for the defense. One team or another is setting a trap: either the offense is trapping an overzealous defender in a useless position, or the defense is trapping the disc into a wind-pinned open throw.

Zone defenses that trap onto the crosswind sideline can be devastating. There is virtually no reason to trap on the upwind sideline unless the wind is also variable enough to create two unpredictable trap locations. When trapping with a crosswind, cup players should stay disciplined. They don’t need handblocks to create turnovers, especially in that pursuing these highlight blocks (especially on yardage-losing throws) can open up holes in the cup going upfield. Instead, zones with a crosswind advantage should generally be willing to allow any backfield throw from which the offense cannot quickly swing to the far sideline. This rachet will generally push the offense backwards, and it takes very few reverse movements in a row before an offensive player will panic.

Offensive Schemes

OFFENSIVELY, THE KEY is to get to the upwind side (typically also the breakside) of the field. Top teams visualize crosswind in one of two ways:

- The high and low sides – If you think of the upwind side as being physically higher, then it makes sense to get the disc there. You can always throw downhill easily, so teams should work uphill first and attack the defense later. There is no sense in climbing and fighting at the same time when you can do them separately.*9 Getting out of trouble moving downwind is far easier than having to make similar throws from the downwind sideline.

- The diagonal field – In no wind, your success in a possession is defined in relation to the distance progressed directly towards the nearest point of your attacking endzone. With a crosswind, though, you can mentally shift the field of importance. Now, movement directly up the field is less important, and can be matched by movement across and upwind. The best throws are those that gain yards and upwind position at the same time, so they’ll will follow a diagonal line. Some teams practice this by playing crosswind practices in which the upwind half of the endzone is worth two points and the downwind half only one.

In this diagram, the relative value of field space is shown in darker color. Without wind, any offense wants to (obviously) move towards the scoring endzone. While the middle of the field is safer, you’d always rather be closer to scoring than not at any particular position. When moving upwind, the sidelines are more dangerous: establishing middle position is relatively more valuable here, even sometimes when the opportunity cost is yards towards the endzone. A crosswind allows some yardage-gaining throws, but the ‘high’ side of the field is crucial. If given a choice, diagonal throws that gain yards and crosswind position are always preferable. A lateral move into the crosswind is just as valuable as a similarly-long move straight towards the endzone. Teams should be fighting to get the disc to the high side of the crosswind!

If you’re trying to throw toward the upwind side of the field, gusts will blow the disc back towards the field instead of towards the abyss of out of bounds. Do this by directly squaring up to face the mark, such that backwards and downfield passes around the mark are both viable without a turning pivot. Look for these moves early. In no wind, a player may spend several seconds looking down the sideline without cost. In crosswind, you can expect that this time is being used by the defense to set up a trap of active, high-pressure defenders with the aid of the wind on all throws. It isn’t an exaggeration to say that players in normal wind should turn to the middle by stall 1 — if there is something to be gained down the sideline, it is typically obvious before any mark arrives.

If nothing else, being closer to the upwind sideline often allows some wind relief as there are tents, structures, and other humans blocking some of the wind (while the downwind sideline is blocked only by 14 bodies). Adding to this point, it can be useful to have your sideline teammates move with the play on offense, even forming a loose wall just upwind of the thrower to protect the disc from flutter in the crucial pullback and release phases of the throw.

If you are caught on the crosswind-downwind sideline, there are a few things to have in mind:

If you’re trying to throw toward the upwind side of the field, gusts will blow the disc back towards the field instead of towards the abyss of out of bounds.

- Defenders get excited in these situations and often foul more frequently. Know your calls and use them if appropriate. Pivoting helps to expose markers who cannot intelligently back away from the thrower and instead overplay their mark to generate a block.

- Bigger, more difficult throws are easier at stall 1 than they are at stall 9. By stall 9, defenders know that they don’t have to stay with their assignment and can roam. Early in the count, you may be able to attack to places that will lock down later. Swings, breaks to the front of a vertical stack, and blades or hammers to the far side of the field can be useful early in the count. These throws have the same visual signature as a lower-level player who is randomly making aggressive decisions, so many coaches denigrate them instead of comparing them to the opportunity cost. But that doesn’t change their true value in beating the other team.

- You might find yourself in a situation with no great options. If you have to choose between different difficult throws, prioritize the equally makeable throws toward your attacking endzone. Occasionally, a crosswind defense will pressure both the upfield handlers and downfield cutter options in equal ways. If they are equally bad options, you should always take the sideline huck over a backwards dump.

After a turnover, offense should be immediately attempting to gain yardage or move to the high side. Reestablish your diagonal field and go for it. Any smart defender will prioritize setting the first mark to keep your team on the downwind sideline, and moving against that mark later will be more difficult than if you had moved quickly. The only exceptions to this rule should be for teams in which the throwing skill difference between players is so great that it is advantageous to wait for a better thrower to walk over and break the mark. If you have that player, use them. If you don’t, move the disc quickly. The right turnover thrown quickly will pay dividends over waiting to appease sideline calls for ‘have patience’ and ‘be chilly’.

Playing In Extreme Wind

Now that we’ve gone over the subtle strategic adjustments you should consider in several different types of wind, it’s time to consider a scenario where subtlety goes out the window — extreme wind.

Playing in extreme wind is a reality of ultimate and failing to prepare for these situations is like driving without a spare tire. It might work out, but if it doesn’t, you have no chance in the race. The changes required are not huge, but teams must be prepared to embrace them.

Extreme Wind Strategy

FOR THE FLIP, you should obviously take the advantage of the wind. This is true in many games at normal and strong wind as well, but I’ve seen teams make the mistake of overthinking this decision in extreme windplay on a number of occasions.

If you are not convinced by the math that you may win the game with an even number of upwind goals, then consider that extreme wind means that you may not reach halftime. If that’s the case, you’ll never reap the benefit of choosing to defer. Also, for emergent extreme wind, your team will gain some experience at moving against the wind over the course of the first half. Second-half upwind goals may actually be easier, especially against a more tired defensive opponent.

In a scenario where you lose the flip for wind, it is normal to choose starting on defense. This combines your advantages for the second half, since that downwind O point will be crucial.

When pulling in a strong or extreme downwind, you might consider backing up to pull. Pulling from behind the line may allow more time for your team to cover the pull and can increase the hang time. Plus, it provides a bigger margin for error if the disc gets pushed farther than you are anticipating. Alternatively, if you are pulling against an extreme upwind, you can do a few things to help your team. Non-pullers should still run hard to cover, in part to stop any rolling or flipping discs coming back towards you. Since the sideline will be tough to use in any case, you may want to try pulling rollers out of bounds. Very adept pullers will ready themselves more than 15 seconds before the time to pull. If they sense a lull in the wind — by feel or by watching nearby foliage — they can pull into that lull even if their team is still discussing strategy.

When you line up your team from Good to Evil, your best players in extreme wind are often more to the evil side.

In extreme wind, coaches and captains may find success with players who have one strong throw. A big backhander without a forehand to speak of can be extremely valuable. There is no need for touch or balance or, in some cases, even accuracy against an extreme wind. Otherwise, the only real important subbing concern is to avoid players who mentally take a long time to transition between situations. Since we expect many turnovers and since those transition times are especially powerful opportunities for the offense, we want players on the field who react quickly and are not emotionally delayed by a single turnover. Every team has a strong handler who really wants to avoid mistakes and play their best for their teammates…that might not be the person you want. Instead, this is a specific opportunity for an experienced hucker with remorse-free tendencies. When you line up your team from Good to Evil, your best players in extreme wind are often more to the evil side.

One common aspect of extreme wind is that calm teams are constantly engaged in The Switch. On offense, the smaller more experienced handlers have the disc upfield while more athletic cutters are downfield. After a turnover, the players need to essentially swap field positions entirely, as the corresponding players on the other team make their way to their ‘ideal’ field position. If you stand back from one of these games and squint, you can actually observe this happening on a field-wide scale in your blurry vision.

When teams fast break, there is no time to complete The Switch, which is why it’s valuable to have players who can operate either as huckers-and-deep defenders (Jonathan Nethercutt is a great recent example) or as cutters-and-handler defenders (Hana Kawai is a great example of this). Not only are they more ready to make plays in extreme wind, but this eliminates 40-50 yards of running after every turnover and replaces it with rest. If you have superstar huckers or massive athletes, you may want to delay transitions. But if you are facing these kinds of players, then you may benefit from long points by consistently increasing the pace to tire out those superstars or simply keeping them out of their best plays.

Timeouts should be considered for any situation that might garner an upwind goal and never used wastefully at the downwind endzone. Many times offenses use timeouts as a rest when the defense is even more tired, which is actually giving away an advantage. Just because you feel horrible doesn’t mean you aren’t on the verge of winning that point or that game.

Punting

AS IS OBVIOUS to most people who have played in extreme wind, purposefully throwing long turnovers (also known as ‘punting’) is a necessary strategy in some situations. Punting downwind is an extreme example of avoiding short turnovers. It is most helpful to have your team on board with this decision rather than it appearing to be a single player making this decision. If not, they’ll spend time complaining that could be used to mark the other team before they have a chance to take free yards.

Downwind punts are often successful when high, so that they can be covered like pulls or occasionally caught. This also lowers the chance for a block near the thrower by an opportunistic defender. Florida used a great downwind punt play where they would send three cutters to the endzone: one to sit under the disc and draw defenders, one to try to catch it by attacking the disc, and a final cutter tasked only with staying behind the pile to catch lofted discs that sail more than expected. At worst, this placed three defenders near the new turnover, which is especially useful for teams who decide to set a zone after a downwind punt.

All defenders in extreme wind should be trying to catch every block, as attempted catches often fall to the ground (because the spin was disrupted) while attempted swats often rise (because spin was maintained).

Punting against zones can be more difficult with multiple defenders to clear. You must avoid the short turnover, so have no qualms about throwing long blade-y throws that roll in order to ensure that your disc gets past the cup or front wall. Your team is already betting on the intentional turnover as a viable strategy, so you’ll need to get over the shame of throwing a completely uncatchable disc if you want to help your teammates.