While the Ultimate Players Association/USA Ultimate has never been an organization that was widely acclaimed for its communication and transparency by its membership, by my estimation, 2007 was a high water mark in the organization’s favorability. The UPA, as it was called at the time, had completed defining its first major strategic plan. It had been an 18-month process that included multiple back-and-forths with members and other stakeholders in the sport (vendors, partners, leagues, parents, etc). The communication took many forms, from very short to very long surveys, individual in-person interviews, small player forum discussion, an online summit, and four large summits in major ultimate locations that drew over 100 people each. The final plan was drafted by eleven committees that included staff, board, and community members.

This strategic planning process was led by the Executive Director at the time Sandie Hammerly, completed by our strategic consultant (and HoF ultimate player) David Barkan, and co-chaired by Board Members Henry Thorne and Elizabeth Murray. I was very involved in the planning process, as it occurred during the period when I transitioned from UPA staff member to the Board of Directors. I moderated several of the small player forums, including those in Baltimore, Minneapolis, and Colorado; created and analyzed most of the surveys; moderated two of the summits (Atlanta and Boston); co-chaired two of the strategy committees and served on others.

While the whole effort was long overdue and the membership was overall skeptical, the process gave the UPA greater insight into the membership’s vision for the sport than it had ever had before. And the plan gave the UPA a robust framework for making confident decisions going forward and facing upcoming challenges. When one member took it upon himself to perform a survey at his local sectional championship and challenged how well the UPA had evaluated the “wants and needs of the membership,” it was easy to provide data that reaffirmed the UPA’s credibility and legitimacy for making decisions on behalf of the membership. And, when Cultimate made a bid to provide an alternative competitive structure for the college division, the organization was prepared for the challenge and could point to its understanding of the need to make improvements and its plan to improve. While the UPA had to accelerate the process of revamping the college division, the organization worked with the Cultimate organizers and college players to make dramatic improvements to the division which have led to the division thriving over the past several years while maintaining stability and quality throughout the process.

All that is to say that the process of developing the 2007-2011 strategic plan gave the UPA a great understanding of its membership’s vision for the sport and an ability to confidently and boldly lead the sport forward. However, in the later years of that five year plan and in the most recent strategic planning period, it seems that any goodwill and trust from the membership that was generated by that process and the in-depth understanding of the membership’s desires has slowly eroded.

We are now at a historic low.

I’ve heard countless players — from relatively new college players to grizzled 20-year vets on elite teams — bemoan recent USA Ultimate developments. If the 2007 strategic plan was a high water mark, the recent planning to shift the Club Series to the summer and the membership’s outright rejection of the plan was a low water mark, underscoring how much goodwill has been squandered and how little USA Ultimate seems to understand about its current membership.

How did we get here?

Governance, Organizational Policies, and Communication

Some of the roots of the disconnect between USAU and its membership can be traced to long before even the 2007 high water mark. Beginning around 2000, the UPA shifted its role and perception of itself from being purely a direct tool to facilitate short-term membership desires (i.e. organizing College and Club National tournaments focused solely on participants) to have a more distinct understanding of the organization’s own needs as well as a view of itself to serve the larger goals of “the sport.”

At the 2002 UPA Board Meeting, the Board of Directors approved funds for the first Director of Youth Development, specifically tasked with “growing” the sport. This was the first time that a significant portion of the organization’s operating budget was spent toward future members instead of current members (Full disclosure: I was that first Director of Youth Development, hired in 2002). Once these funds were allocated, a barrier was crossed that now called for the UPA and its Board of Directors to begin balancing current player needs with a longer term vision for the sport that considered the needs of future players.

Once these funds were allocated, a barrier was crossed that now called for the UPA and its Board of Directors to begin balancing current player needs with a longer term vision for the sport that considered the needs of future players.

Later in 2002, the UPA — seeking to improve its long-term planning — hired its first Executive Director who was not a current or former player, Sandie Hammerly. Hammerly brought a higher level of professionalism to the UPA, but not without a move away from player-influence of the sport. No matter how great of an executive leader the UPA/USAU has, it’s undeniable that that person has enormous influence and brings their own sport and organizational experience and vision. Hammerly did a tremendous job of executing the vision of the Board of Directors and the fingerprints of her own vision in the 2007 strategic plan were light. The biggest impact of Hammerly’s light touch was acclimating the organization and its members to an executive leader from outside of the sport.

Along with thinking more long-term about the sport, this period was marked by thinking long-term about the UPA’s continued existence. As you would expect any maturing organization to do, the UPA worked to establish greater financial reserves and put more effort into risk management and avoidance. Similar to spending money on youth development, saving money for future rainy days is a move away from serving the immediate needs of current players. And risk-management meant implementing policies that players didn’t love but were seen as important for the long-term health of the organization.

Even now, it’s easy to see the values that each of these changes brought to the organization and the sport in the longer term. And while they all brought compromises in terms of the experience of UPA members and their influence on the organization, there was wide community agreement with these changes and the vision of what was good for the sport.

2005 Rejected Board Restructure

THE SUCCESS OF these early future-looking initiatives served to validate the Board’s increasing confidence in defining a long-term vision for the organization — and ultimately the sport. This was further emphasized by a Board restructure proposal shortly thereafter.

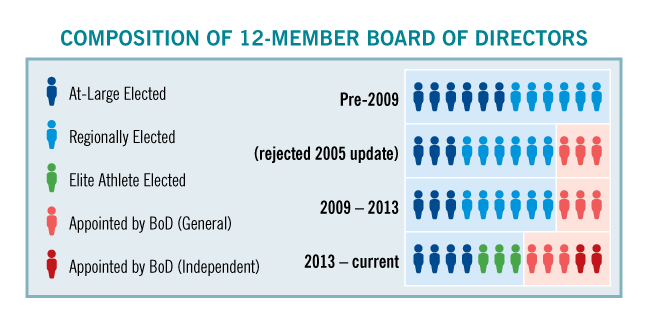

At the January 2005 Board Meeting, Board Member Mike Payne submitted proposal 2005-9 to change the method for electing Board Members. The proposal sought to reduce the number of membership elected Board Members from all twelve to nine (with six regional representative and three at-large representatives). Taking the place of the three Board positions that had previously been membership-elected would be three Board appointed (“Board-elected”) positions.

The proposal hoped to help professionalize the UPA Board by ensuring that certain skills and knowledge (IT, Management, Legal, etc.) were present on the Board at all times. In the Board Meeting minute notes, the proposal is called “draconian.” The Board presented alternatives to ensuring the necessary skills to run the organization, including “adding members as needed” and “hiring consultants” instead of reducing member-elected positions. The meeting minute notes indicate a concern that the proposal would reduce the incentive for the Nominating Committee to aggressively recruit qualified Board candidates and it is noted that there should be a “distinction made between skills (sic) sets needed on the Board and voting responsibilities needed on the Board.”

The proposal was tabled by a vote of 11 for tabling with no votes against or abstentions. Still the rejected proposal to update the bylaws is useful to highlight much of the trend of the UPA/USAU’s movement to disconnect from the membership over the past decade.

Tom Crawford

IN 2006, THE UPA began its first strategic planning process (described above), which clearly indicated that the membership was behind more youth outreach and development, observers, and revamping the college and club structures. Yet throughout the implementation of the 2007-2011 strategic plan, it became clear that the UPA needed even more leadership experience to oversee the growth of the sport and organization that the membership wanted and expected.

I was on the Board of Directors in 2009 during the executive search following Hammerly’s departure and it was hard to ignore Tom Crawford’s extensive experience and his connections. That said, the strategic plan in place at the time was, at its heart, a grassroots development plan while Crawford’s resume was steeped in media, the Olympic movement, and big sports business. While incredibly attractive to a sport that has always struggled with a bit of an inferiority complex, Crawford’s skills and experience didn’t align tightly with the strategic plan’s goals.

But, after the experience with Hammerly’s light touch as Executive Director, it was understandable that we believed that Crawford could bring his talents to bear as a tool of the Board of Directors in executing the Strategic Plan and the will of the membership without imposing too much of his own vision and predisposed understanding of success in the sports world. And, while that Strategic Plan had no consideration or thought of the Olympics as a goal, if we thought we could move closer to that goal without compromising the Strategic Plan, who could blame us?

Crawford asked for more than our stated salary range on the job posting. In the full Board discussion, I was one of the first people to express support for offering the position to Crawford — at the salary he was asking — because I believed that the organization could use his skills and experience to achieve our goals.

Needless to say, Crawford’s influence on the overall vision of the organization has been far stronger than Hammerly’s ever was, even early on and in opposition to that first Strategic Plan. As his influence has been increasingly felt, the influence of players has waned and the disconnect between the organizational vision and the members’ vision has grown ever wider.

Ultimate Players Association to USA Ultimate

IN MANY WAYS, the name change from the Ultimate Players Association to USA Ultimate that occurred on May 25th, 2010, has felt to many as the turning point for the organization away from representing the players and toward representing “the sport.” It’s almost explicitly stated in the vocabulary of the names.

For many members, the name change represented a symbolic shift in perspective for the organization. No longer are “players” at the center of the organization.

From the mid-2000s, I had pushed hard for the name change. At the time, as the staff member who most frequently represented the sport and organization in the non-ultimate sports world at events like Physical Educator conferences, I believed strongly that the name “Ultimate Players Association” held back communication about the sport with outsiders. We would attend these conferences with many other vendors and presenters including more established National Governing Bodies like US Rugby or USA Badminton. Whenever we talked to a physical educator, before we could even explain that we were a sport, we’d have to explain why our name was different than other, similar organizations. I felt that countless, potentially interested physical educators would walk by our tables or skip our presentations without even inquiring because our name was so inaccessible.

At the time, it never occurred to me that for any internal (member to organization) purposes, a name change could make any difference. But, for many people, the name change represented a symbolic shift in perspective for the organization. No longer are “players” at the center of the organization. Whether or not the name change represented an actual shift in attention by the organization, at this point, it’s undeniable that, for many members, there was a perceived shift in how the organization valued their role in the sport vs. the role the members played. Players felt alienated.

Organizational Growth & New Policies

SOME OF THE growing disconnect between USA Ultimate and the players has been due to organizational growth, maturation, and changes in personnel policies over the past several years.

In 2002, when I began working at the Ultimate Players Association, I was the fourth full-time UPA employee. Of the four of us, three of us played on Nationals-caliber teams and, for the next few years, our policies (both formal and informal) were very player-friendly. Flexible work schedules allowed us to travel to practice, coach, or play events. One such informal policy was that if more than half of the staff was competing in Club Nationals, no vacation days were required.

These policies allowed the staff at the time to remain very much integrated with the competitive ultimate scene. We were supported in our efforts to play for committed club teams. And, while I don’t recall spending a great deal of time talking about the UPA at Johnny Bravo practices or at tournaments, that support allowed us to be a part of the community, feel the impacts of our work, have our faces known, and regularly connect with volunteers around the country.

By late 2011, the USAU had updated the policy around staff competing at Club Nationals. The new policy didn’t just eliminate the potential player-staff to not have to use vacation days to compete at Club Nationals, it prohibited any new USAU staff from competing at Club Nationals. While current staff were grandfathered in, this new policy ensured that players with elite club ambitions would no longer seek employment with USAU.

Now obviously elite club play isn’t the only venue for being a “player,” but this policy actively dissuades many of the most active and involved members who aspire to compete at Club Nationals from working for the organization. And, just as importantly, it denies USA Ultimate staff the opportunity to be a player-face for the organization just by their presence at the elite club tournaments they would attend. While these policies are understandable from a professionalism level, they marked another key step in the divide between ultimate players and the organization that represents them.

At the same time, having a maturing organization meant employing a more mature staff, some of whom would have been aging out of club play anyway. While there is enormous benefit to having professional experience and strong institutional knowledge in leadership positions, becoming a lifelong employee of an organization like USA Ultimate has the potential to bind a person to the interests of the organization instead of the players and membership itself.

In Crawford’s efforts to increase the capacity and the professionalism of the organization, USAU has brought on many people with great professional experience who are past their playing years. Of course, these personnel decisions have incredible upside; USAU has a tremendous amount of work to do and having staff with more extensive life and work experiences provides value. But as the key decision-making personnel of the staff have moved from players in their 20s and 30s who are active participants in the ultimate scene to former players who are in their 40s and older, the day-to-day connection with the vast majority of ultimate players diminishes. This change impacts the perception of both sides: current player-members feel less peer-to-peer connection with USAU and USAU staff rely on experiences as players that are increasingly further removed from those representative of today’s competitive athletes when making decisions.

Board Communication & Transparency

AT THE HEART of USA Ultimate’s growing disconnect with the membership has been the Board of Director’s ongoing lack of communication and transparency with the membership. While there have been occasional periods of great communication (such as the 2006/7 strategic planning period), the status quo has been pretty dismal.

That current state of affairs has been marked by a handful of Board proposals to create new communication mechanisms with the membership and increase transparency that were rejected or tabled until everyone forgot about them. Most notably:

- In January 2009, Andy Lovseth and Ben Wiggins, who (among other roles) were at the time editors for the online ultimate publication The Huddle, submitted a proposal to hire an ombudsman, who would be responsible for objectively reporting to the membership in every quarterly newsletter. The proposal was aimed at helping bridge the gap between the UPA HQ and its membership. The proposal was voted down with one vote for, nine against, and two abstentions.1The meeting minutes indicated that the reasons for the proposal’s rejection was that Board Members were responsible for that “service,” and the Board and staff had already begun implementing additional mechanisms to improve communication including the President’s column in the magazine, a board blog, and a public statements page on the UPA’s website. Of those, the blog never took off as board members rarely posted to it and members rarely visited or commented on it; the public statements page disappeared with the USAU’s rebranded website the following year. The President’s column has remained a fixture of the USAU’s magazine and one could argue that it meets the needs of the proposal (although, many would argue that it serves more of a “marketing” purpose than a transparency one).

- In June 2010, Board Member John Terry submitted a proposal to the USAU Board of Directors to post the Board Meeting Agendas and Proposals publicly at least forty-eight hours prior to Board Meetings. The meeting minutes indicate that the goal of the proposed policy was to increase transparency, improve feedback from the membership on active proposals, and help get people interested in governance of the sport. Objections to the proposal included challenges with the timing and a concern that “people don’t generally want to see how the sausage is made.” The proposal was voted down with 0 votes for, 11 against, and one abstention.

- In January 2011, Board Members John Terry and Colin McIntyre proposed that individual board votes be published along with the Board Meeting minutes. The proposal was voted down with four votes for, seven against, and one abstention. The justifications included concerns that publishing votes would interfere with Board Member decision-making for what was best for the sport, that the practice of publishing votes is not considered best practice, and the idea that the discussion notes themselves provide more useful information than who voted for what. This proposal would have allowed USAU members to understand which board members supported which ideas, a vital mechanism in allowing players to have a say in the future of the sport.

- In January 2015, a Gender Equity Ombudsgroup proposal was submitted to the Board by an outside group including former UPA BoD President Peri Kurshan. While not as broad as the previous “transparency” related proposals, this one hoped to create an objective mechanism for evaluating USAU’s performance relative to its gender equity policy, first adopted in 2008 and further amended in 2013. The proposal was removed from the January 2015 Board Agenda on the grounds that it was prematurely added to the agenda and there hadn’t been enough time to prepare for the discussion. It was taken up again on the Spring 2015 Board Call and, on recommendation of the Marketing Working Group, the proposal was rejected by a vote of two for, nine against, with one abstention. The published reasoning for the rejection included that the proposal was too narrow in its use of broadcast exposure to define equity, a reference to the USOC’s requirements on Board and Staff roles, and, similar to the others, a concern about redundancy.On that call, the Board did create a Board-staffed “Equity Task Force” to address the underlying concerns that led to the ombudsgroup proposal. This task force has since organized two community forums and a retreat for the task force itself and senior USAU leadership with Janet Judge, a leading equity expert. As of February of this year, the task force has been upgraded to a standing working group with plans to update the Gender Equity Policy. Whether or not this effort succeeds in addressing the concerns that led to the Gender Equity Ombudsgroup proposal remains to be seen.

The pattern here is unmistakable. Members call for increased transparency and suggest new mechanisms that achieve that. The Board rejects the suggested mechanisms and either voices their confidence in existing mechanisms or implements new mechanisms to address the concerns. Those mechanisms either disappear or do not fully address the membership’s concerns around transparency. Membership calls for increased transparency continue.

The consistent expression throughout these proposals is that a higher level of transparency and communication between the Board — the membership’s elected representatives — and the membership itself is desired.

I don’t want to suggest that transparency is easy for an organization like USA Ultimate. Clear, concise distribution of information is challenging in a large membership organization where decisions are frequently made by large groups and have to take into account a diverse audience of stakeholders. It’s impossible to expect a single point of communication (like a single ombudsperson or a communications director) can translate all the information demands (both voiced and unvoiced) from the membership, get answers from all of the decision makers, and then communicate it exactly to the people that need them.

However, the consistent expression throughout these proposals is that a higher level of transparency and communication between the Board — the membership’s elected representatives — and the membership itself is desired. All too frequently, the answer seems to be “that’s why we have a Board of Directors.”

This circular process which continuously repeats itself has further distanced the membership from USAU.

2009 Board Restructure

IN 2009, MIKE Payne, Josh Seamon, and John Terry presented a proposal to restructure the Board that was substantively identical to the proposal that had been tabled by the Board four years earlier. This time, the proposal to reduce the number of elected representatives from twelve to nine and replace those eliminated elected positions with appointed members was passed with a vote of nine for, two against, and one abstention.2

In the meeting minutes, there is one line that addresses the impact of restructuring the board on the potential disconnect:

“We need to make sure we don’t lose our connection to the community.”

There was some talk of expanding the board to 15 members to reduce the impact of the decreased connection to the community, but that was resolved by a straw poll with only three for, seven against, and three abstentions.3

The notes from the Board meeting indicate an organization conflicted between representing the membership and ensuring that it was capable of executing what the membership wanted. The decision to restructure was a step away from representation and a step toward execution.

2012 Strategic Plan

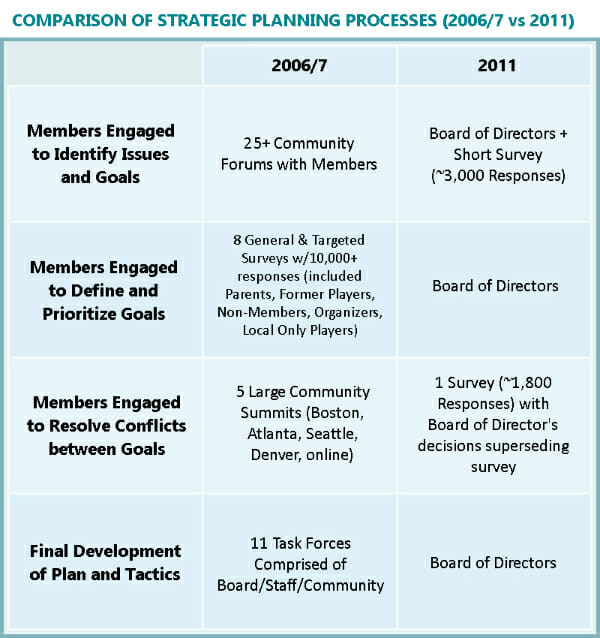

IF THE 2006/07 Strategic Planning process is our baseline of UPA/USAU membership engagement, the 2011/12 strategic process marks a critical contrast in the organization’s self-defined role within the sport.

For the 2006/7 Strategic Plan, the UPA brought in David Barkan, an organizational psychologist and principal of Barkan Consulting Group with a long history in guiding nonprofits and philanthropic organizations through large-scale change processes. Within the ultimate community, Barkan is also a long-time player and the CEO and co-founder of Ultimate Peace. This is to say that Barkan was both an expert in leading strategic planning processes as well as someone who already had a deep understanding of the community.

For the 2011/12 Strategic Plan, USAU brought in Kae Rader of Rader Consulting. Rader, too, has deep experience with organizational and leadership consulting, including strategic planning for other US sport NGBs such as USA Shooting and USA Weightlifting. Rader had previously spent time as the Executive Director of US Table Tennis and in various roles at the USOC for over eight years. Rader literally wrote the handbook on governance for National Governing Bodies.

USAU discussed using Barkan again in 2012 but chose Rader for her USOC and sports industry connections and experience. While there is no doubt that Rader has excellent qualifications, this choice represents another decision to value the influence of traditional sports industry over members of the ultimate community.

The two strategic planning processes could not have been more different. In 2006/7, Barkan led the Board’s strategic planning committee through a process marked by high-engagement of the existing membership. It began with dozens of small (6-20 person) forum discussions to define the issues. Participants were prompted with open-ended questions like “What sucks about the UPA/ultimate?” and “What do you love about the UPA/ultimate?” From there, the strategic planning committee reviewed pages of notes and identified common themes. We reached back out to the community in a comprehensive survey to help them prioritize the identified issues and put objective data against the subjective feedback we’d received. That data was then summarized and presented back to players in large community summits — both online and in-person — where players were asked to consider the data and suggest how we allocate our resources against each one. Finally, that data was compiled and 11 sub-committees — made up of both the Board and community members — created plans that were, once again, sent out to the community for feedback before our final plan was ratified and released. All told, there were over 10,000 survey responses and several hundred people engaged in-person through the strategic planning process.

In contrast, the 2011/12 process could charitably be called “siloed.” In May 2011, USAU sent out a survey to members to gather preliminary information. Instead of starting from a blank slate, as the 2006/7 process did, all of the survey’s non-open ended questions asked specifically for feedback about the 2006/7 strategic plan and the organization’s execution of that plan. In addition, there were a handful of open-ended questions about the organization’s mission statement, strengths, and weaknesses. This survey garnered just under 3,000 responses.

Some of the most notable responses to the survey included:

- Overwhelming support for “grow and enhance youth ultimate” (69% calling it “extremely important”)

- Widespread support (over 80% responding with “extremely important” or “very important”) for the following strategies:

- Promote, clarify, and support Spirit of the Game as a unique quality of ultimate

- Expand women’s participation at all levels

- Improve field access

- Build college ultimate through team and sport administrator relationships

- Improve player knowledge of the rules

- No questions were asked specifically concerning “promoting visibility of the sport.”

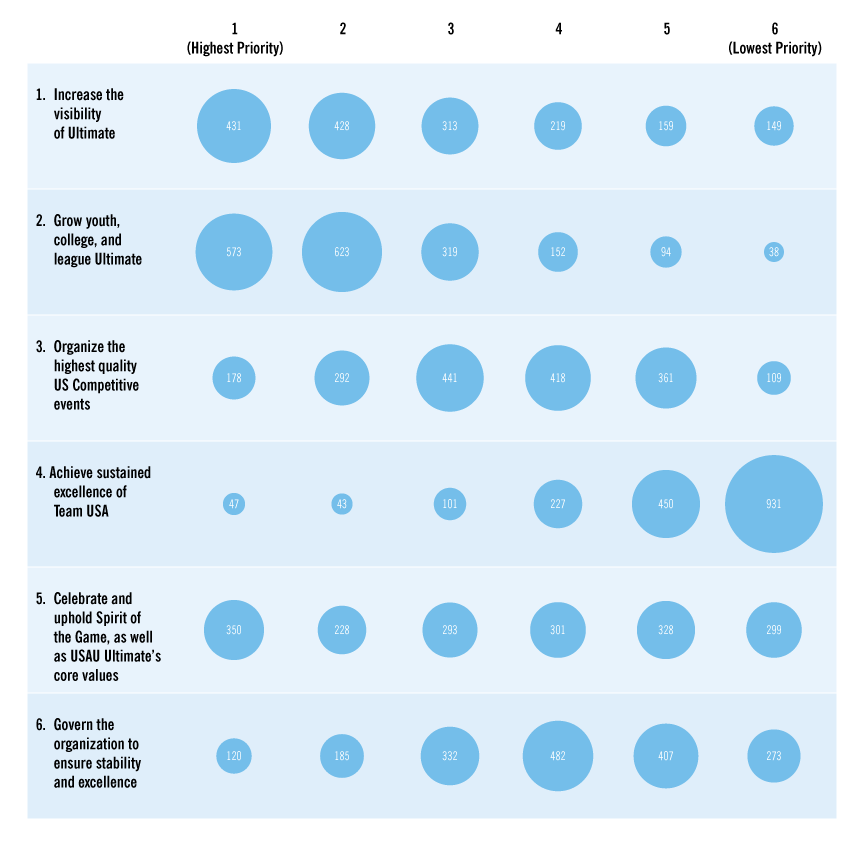

Rader then led the Board through a retreat process to identify the biggest issues and goals of the organization and strategies for each. Six goals were identified:

- Increase the visibility of ultimate

- Grow youth, college, and league ultimate

- Organize the highest quality US competitive events

- Achieve sustained excellence of Team USA

- Celebrate and uphold Spirit of the Game as well as USA Ultimate’s core values

- Govern the Organization to ensure stability and excellence

From there, a survey was sent out to membership in November 2011 to rank those goals as well as the strategies within each goal. That survey received just over 1,800 responses. The Board then put together a final strategic plan without any additional player engagement.

For those who have been following USAU’s actions in recent years, they rely heavily on the 2011 strategic plan to justify many of their decisions, frequently claiming that the membership’s voice is represented in the strategic plan and their number one goal is “Increase the visibility of ultimate.” However, in addition to the fact that the membership was only engaged on a wide-scale in that one survey, the results of the survey indicate that “Growing youth, college, and league Ultimate” was in fact the number one goal of the survey respondents.

The decision to prioritize “visibility” — and every subsequent decision made under the guise of this justification — is one made by the USAU Board and Staff in opposition to the will of the membership. When asked about the decision to prioritize “visibility,” Mike Payne, longtime USAU Board President and chair of the 2012 Strategic Planning committee, responded:

I have been, and am, in involved in the leadership of several organizations, including private companies, where I have taken a leadership role in strategic planning processes. It is a discipline in which I am both academically and professionally trained. In stable, long-term organizations that have responsibilities to their constituents (whether they be dues-paying members, employees, shareholders, or other members of a community), it is the job of the leadership, when planning, to account for both the needs and desires of the current stakeholders, as well as the ‘envisioned’ needs and desires of the future stakeholders. In considering these two groups, their priorities may not always be exactly aligned, and in those cases, it is the job of the leadership to determine appropriate trade-offs and decisions based on them. In the case of the past ~7 years at USA Ultimate, I believe that the Board and CEO have made careful and effective decisions about the future of USA Ultimate in the majority of cases.

Ben Banyas, another member of the strategic planning committee was more forthcoming in explaining how “visibility” became the highest priority strategy for USAU. He explained that the Board believed that increasing visibility would help achieve all the other strategic goals listed. So, in effect, visibility was not only a strategy in itself but a necessary tactic for every other strategy.

USAU leadership has frequently justified this decision [to prioritize visibility] as in the interest of “future stakeholders,” with those interests being defined solely by the Board of Directors.

While many of USAU’s decisions that have made them less engaged with the membership are justifiable in that those decisions help them to achieve the ends that the membership said they wanted, this one is difficult to justify because it calls into question exactly those ends.

On the whole, the 2011 strategic planning process sought far less input from the membership and, when input was received, it was not regarded as highly. USAU leadership has frequently justified this decision and others related to it as in the interest of “future stakeholders,” with those interests being defined solely by the Board of Directors. In the 2012 Strategic Plan, USAU failed to adequately identify the membership’s interests, give an opportunity to the membership to weigh goals against each other and have their voice heard on strategic trade-offs, or validate the final plan as being what the membership wanted.

2013 Board Restructure

IN 2013, AN updating of USAU’s bylaws — which again restructured the Board of Directors — continued the path of reducing direct membership representation on the Board of Directors by expanding the number of appointed Board Members from three to five. In addition, the new bylaws required that three of the appointed board members be “independent,” which is defined as “having no association with ultimate for the past two years.” Further, three of the remaining seven member-elected positions were designated as “Elite Athlete Board Members,” positions for which only a small subset of USAU members who meet “Elite Athlete Requirements” were eligible to either run or vote for.

Each of the changes was justified with separate reasonings. The “independent” Board Member positions were established to “reduce potential for intra-sport conflicts,” while the “Elite Athlete” positions were established to ensure player representation on the Board of Directors. Both changes were made to align USAU with standard NGB best practices, a requirement from the US Olympic Committee (USOC). The other appointed board positions were kept to ensure expertise and high-level skills in specific areas required of the Board while the regionally-elected positions were eliminated as they were no longer seen as necessary to protect and serve the interests of the players in each region.

The updated bylaws were accepted by the Board of Directors unanimously (12-0-0) on April 6th, 2013. They were then reviewed by the USOC for approval before becoming effective. This new external oversight was required for USAU to remain a USOC Recognized Sport Organization, necessary to maintain the potential of Olympic inclusion.

In just four years, from 2009 to 2013, the membership went from electing 100% of the twelve member USAU Board — of which every member could vote on seven (as six members were regionally elected) — to having a vote on only 58.3% of the Board, with the majority of membership only having a vote on 33% (the four at-large board members), as three members are elected only by “elite athletes.”

Furthermore, as opposed to the discussion of the 2005 rejected bylaws update where appointed board members were considered “draconian” and the 2009 update to the board composition where there was concern about reduced player influence, in 2013, creating “independent” board positions who were not active within the sport was highlighted in the Board discussion as an advance in Board Governance. In just eight years, the Board’s perception of unelected, non-player Board Members had gone from “draconian” to “concerning” to “necessary.”

Perhaps even more notably, USAU recognized that one of, if not the biggest, stakeholders in the organization’s bylaws — the very rules by which we govern ourselves — was the USOC. Over the course of four years, the bylaws had been rewritten, in part, for that body’s approval and were not effective until that approval had been received.

No moment so well signifies the shrinking influence of the player’s will and desire and the growing influence of non-ultimate forces as the 2013 Bylaws update.

What, of course, makes this complicated is that pursuing USOC and Olympic recognition is arguably a significant goal of the membership. Plus, the tools that recognition provides to USAU are useful in achieving many of the other goals of the membership. Moreover, the requirements from the USOC include ensuring player representation on the Board. The disconnect, however, is that our sport had traditionally elected active players; the new Bylaws restricted which “players” could run for and vote for 25% of seats. In the same stroke as guaranteeing player representation, the new bylaws ensured much greater influence of non-players than the Board had ever seen before.

What, of course, makes this complicated is that pursuing USOC and Olympic recognition is arguably a significant goal of the membership. Plus, the tools that recognition provides to USAU are useful in achieving many of the other goals of the membership. Moreover, the requirements from the USOC include ensuring player representation on the Board. The disconnect, however, is that our sport had traditionally elected active players; the new Bylaws restricted which “players” could run for and vote for 25% of seats. In the same stroke as guaranteeing player representation, the new bylaws ensured much greater influence of non-players than the Board had ever seen before.

It should be noted that the new bylaws were accompanied by a new model of player and member influence: working groups. These small groups of representatives are involved with advising the Board of Directors and help the Board make decisions that affect their constituencies. Currently there are 26 active USAU committees and working groups, 18 of which have non-board and USAU staff involvement. Working groups include the “Rankings Working Group,” “Rules Working Group,” and the “Youth Outreach and Education Working Group.”

The majority of those non-Board/Staff working group members either volunteer or apply for their position and are appointed by USAU. The exception to this is the six club division representatives elected to the Club Working Group (two each for the women’s, mixed, and men’s divisions).

Working groups perform in an advisory capacity, not a decision-making one. The 2013 Bylaws update was a firm move of players (and player-elected representatives) from a decision-making role for the organization to an advisory role.

Return to the Springs

IN 2002, THE UPA moved its office from Colorado Springs to Boulder. At the time, for where the sport and organization were in development, the governing body’s presence in the city that provided the Headquarters for the USOC was not providing significant benefits. The UPA was too small to even get noticed and there were rarely valuable interactions with other National Governing Bodies. The ultimate scene in Colorado Springs was small and there was no high-level team nearby, which had a negative impact on the quality of life for staff of the organization and impacted the draw for new potential staff. As they sought an alternative home, the UPA considered Atlanta and Seattle, but chose Boulder for its accessibility to all parts of the country and the relatively low cost of living while still allowing the organization to remain close to Colorado Springs.

In December 2014, USAU announced that after twelve years away, it was returning once more to Colorado Springs. As the press release indicates, the move was primarily driven by the desire to further strengthen USA Ultimate’s “alignment within the Olympic movement.”

As with all of the recent decisions, the relocation to Colorado Springs was a complex one. The Colorado Springs ultimate scene has grown, but is still significantly smaller than the ultimate community that the organization left behind in Boulder. Perhaps more importantly, the lifestyle and culture of Boulder is significantly more in line with the sport’s historical culture than the lifestyle and culture of Colorado Springs.

The move has put pressure on many of the still involved player-staff. In the months following the move, two staff members left due, at least in part, to the relocation including Manager of Youth and Education Programs, Mike Lovinguth, and long-time staffer Director of Membership and Sport Development, Melanie Byrd Deaver. Will Deaver, the longest-tenured USAU employee, is currently commuting from his home in Louisville, CO, a 90-minute ride each direction. Other staff I’ve spoken with have expressed their unhappiness with Colorado Springs as well, and players who might otherwise be interested in working for USAU are turned off by the location.

To be fair, some people from our community who are highly qualified and who have connections with the larger Olympic movement, including former USAU Board Member John Terry, have expressed a greater likelihood of working for USAU now that it is in Colorado Springs. Unfortunately, community members that are also highly networked to the larger Olympic movement or sports industry are few and far between. And, while the move to Colorado Springs will give USAU access to more resources and expertise in the world outside our sport, it further moves the decision making away from the influence of players.

The 2015 Board Election & 2016 Bylaw Updates

THE DRIFT OF USAU from the membership is still ongoing. One of the changes from the 2013 bylaws rewrite was a requirement that 1% of USAU membership must vote in Board Elections for the results to be valid. Article IX, Section 9.3 states:

Member Quorum. One (1%) percent of the members of USA Ultimate shall constitute a quorum for the purposes of electing the Board of Directors. One (1%) of members who are Elite Athletes shall constitute a quorum for the purposes of electing Elite Athletes to the Board of Directors.

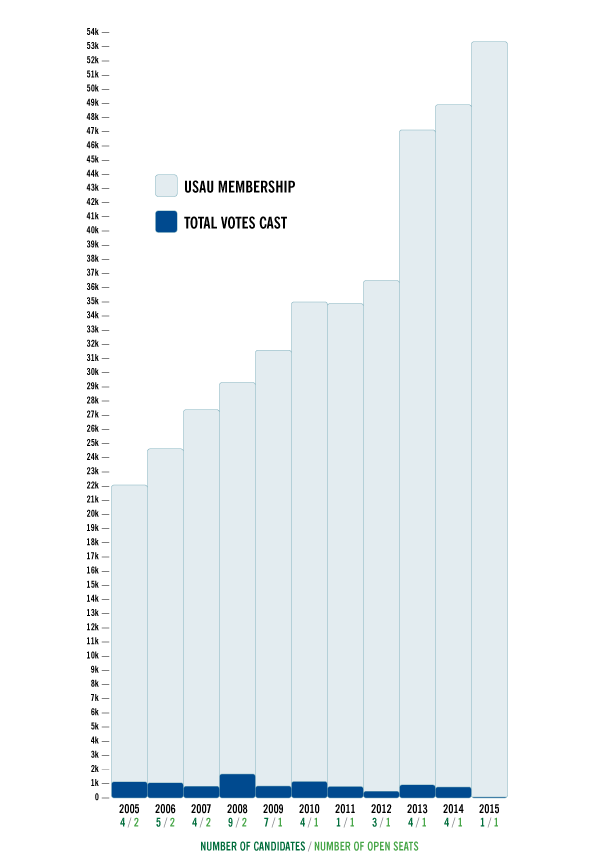

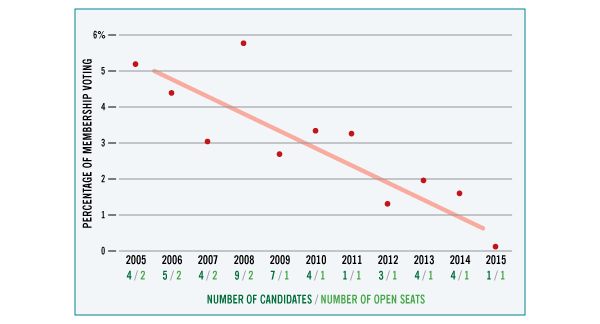

In the fall 2015 Board election, Henry Thorne ran unopposed for the at-large Board Position. He received 63 votes. USAU had 53,362 members at the end of 2015, meaning that Henry received votes from just over 0.11%. USAU has confirmed that only 63 people voted in the 2015 at-large election.

When asked about falling short of the number of voters quorum required in the Bylaws, Andy Lee, USAU’s Director of Marketing and Communications, responded:

Throughout the election, it became fairly evident that the 1% threshold was unlikely to be met given that he was running unopposed. As a result, the board prepared to address the issue following the conclusion of the election process. Once the election ended, the board, via an electronic vote, validated the results and approved Henry’s position as an At-Large member. Given the recent trends of candidates running unopposed and a decrease in voter participation, the board anticipated that this could continue to be an issue in the future and addressed that by approving an amendment to the bylaws which removes the 1% requirement for a quorum.4

Andy Lee later noted that “the decrease in percentages are not unexpected as the average age of our members gets younger and youth participation increases.”

At the February 2016 Board Meeting, the Board voted to update the Bylaws to remove the 1% quorum voting requirement. Setting aside whether or not the Board actually has authority to certify an election that does not meet the organization’s own bylaws, when faced with declining membership engagement, the Board immediately chose to remove the minimum requirement for membership engagement rather than find ways to engage the membership to ensure that the minimum was met.

Conclusion

WHILE GOVERNANCE IS rarely the most exciting part of our sport — or any sport — the decisions made over the past ten years have charted a course that has driven our governing body further and further from the people that play it and more and more toward outside influences. Those decisions are felt throughout the organization and include Executive Leadership, Board Composition and Policies, Staff Policies, Office Location, and Strategic Planning.

Many of these decisions can be justified as helping to fulfill the desires expressed by the membership but, given deficiencies in the 2012 Strategic Planning process, there is a very real question of what the membership actually wants from the sport and organization. Moreover, decisions have so frequently reduced the player influence on the organization that the balance of player influence and outside knowledge and influence has moved toward a tipping point and there currently exists very few mechanisms for membership to influence the sport. Even a concerted membership effort to reassert their influence and put mechanisms back in place to consistently influence the sport could take up to three years of board elections to ensure that every player elected position is representing player’s interests.

And, of concern, if those elected Board Members don’t actually vote according to player interests, we will never even know.

Reduced Player Influence And Impact

hile part one of this piece dealt with the governance of the sport and how the bylaws and policies of USA Ultimate have had a direct impact on the influence of players in the direction of the organization, part two turns to the decisions made by the organization and their impact on the participants of the sport.

hile part one of this piece dealt with the governance of the sport and how the bylaws and policies of USA Ultimate have had a direct impact on the influence of players in the direction of the organization, part two turns to the decisions made by the organization and their impact on the participants of the sport.

The pattern of disengagement of UPA/USAU from the community and reduced player influence on decision making at the organization has led to a significant number of decisions that have been widely seen as having a negative impact on the player experience. Many of these decisions have been justified as necessary to achieve the wider goals of the membership and in the best interest of the “sport.” But with the shortcomings of the 2012 strategic planning process, the lack of transparency on the board, as well as the quickly changing landscape of the sport, there are very real questions of “what does the membership want?” and “who determines what is in the best interest of the sport?”

Drinking and Partying

PERHAPS THE EARLIEST policy changes that could be perceived as having a negative impact on the player experience were those around alcohol at events. Throughout its early history, ultimate tournaments were not complete without a party. Even the most high-profile events of the year with the biggest competitive draw — like the Boulder 4th of July tournament and Labor Day in club, Stanford Invite and Yale Cup in college — featured parties with tournament-funded alcohol. UPA-organized events followed this trend as well, including a beer truck at the Club Championships and tournament parties at the College Championships. Even some sectional and regional events had tournament parties, with tourney entry fees used to fund alcohol.

As the UPA began efforts to grow youth play, the free flow of alcohol became a liability risk. For me, as the Director of Youth Development at the time, the conflict was brought into stark relief at the 2004 Club Nationals. At the time, the UPA provided a beer truck to serve free beer to event participants on Friday and Saturday of play. While there may have been a nominal effort to check IDs to make sure that beer wasn’t provided to those underage, in my role at the UPA, I knew many of the top youth players who were in attendance at the event and it was clear that we weren’t doing much to prevent them from drinking beer purchased by the organization. For the January 2005 Board Meeting, I submitted a formal policy to restrict alcohol distribution and consumption at UPA events. The policy was essentially to create beer gardens where access was restricted coming in and alchohol could not go out. The policy passed the Board 12-0.

For the college division, that policy wasn’t really adequate. It was hard to justify spending money on a party with alcohol for event participants when a significant portion of the event’s participants were not able to attend the party by UPA policy. On top of that, it was clear that underage players were sneaking into the party at the 2005 College Championships. Because the community was small and UPA staff was familiar with so many players, again we were aware of underage players drinking UPA-purchased alcohol. By 2006, the organization-sponsored College Nationals party was no more.

After the organization became USAU, the concerns about alcohol in the sport continued. Notes from the summer 2010 Board Meeting indicate that the organization would work to continue to refine the alcohol policy. CEO Tom Crawford’s perspective is specifically noted:

I love the sport. I want to sell it to lots of people: Families. If I was a parent and I brought my kids to the Club champs, I would not want to introduce them to Ultimate that way. This is not like other national champs for other sports. I witnessed phenomenal competition, blended like Iʼve never seen before with lots of drinking. “Elite” athletes pounding beers. Weʼre putting the organization and sport at huge risk. I want to be able to invite lots of kids to the events like Sarasota to create big fan base and growth.

There’s a lot to unpack here: the concept of “selling” the sport, the desire to be like other sports, the projected needs of families and fans pitted against the players’ freedom to make adult choices, the question of what the “sport” is. But, what is most striking is the vague idea of a “huge risk.” Even more than the goals of growing the sport and exposing it to more families, the fear of litigation is a big motivator for an organization like USAU. But unlike the previous discussions on alcohol that were specifically about ensuring that USAU-funded alcohol wouldn’t make it’s way to the hands of underage athletes — a very serious liability risk –the liability issue here is only mentioned vaguely in passing and it’s not particularly clear why USAU would be at risk from athletes of legal age purchasing and consuming their own alcohol.

In November of that same year, the USA Ultimate Waiver was updated to include a new clause regarding athletes’ consumption of alcohol at USAU events:

6. I agree that, as a USA Ultimate member, player, organizer or representative of the organization, I will not compete at USA Ultimate official, sponsored, sanctioned or affiliated events, or carry out responsibilities related to official organization & event business, while under the influence of alcohol or illegal/banned drugs.

According to USAU’s Andy Lee, the addition was part of a policy adopted on October 19th, 2010. There is no available documentation regarding this policy change.

In January 2012, a new drug and alcohol policy was submitted by Board Member Mandy Eckhoff that would prohibit playing while under the influence of mood altering substances (including alcohol) at USAU events. This policy would bring USAU’s official stance in line with what had already been in the waiver for over a year, however, the policy was tabled with a note about more research to be done. The two cons of the policy listed were “difficult to enforce” and “Potentially in conflict with how Ultimate events are organized (i.e. tournament party).”

Currently, USAU is unable to provide a full alcohol policy and there is no documentation for when that policy and the new waiver was approved. Whether or not such a policy makes sense and would be favored by the membership, it is concerning that a change that impacts the player experience and culture appears to have been made either without any Board-level approval or, at the very least, with no documentation.

Censorship

IN A SIMILAR vein, irreverent, inappropriate names have long been a staple of ultimate. For the first few decades of the sport’s existence, ultimate players delighted in subverting cultural norms through self-expression in naming their teams — or, as others may interpret some of these names, they delighted in juvenile, offensive behavior. New York’s top men’s club team, after a series of national championships in the early 90’s under the name “New York, New York” went by both “Cojones” and “We Smoke Weed” for different National-level seasons, in the mid-90’s.

There’s a lot to unpack here: the concept of “selling” the sport, the desire to be like other sports, the projected needs of families and fans pitted against the players’ freedom to make adult choices, the question of what the “sport” is.

When the sport and UPA were focused almost entirely on the desires of the players, there was never a serious discussion about whether such choices should be allowed. But, a 1998 Wall Street Journal article that called out the “identity crisis” within the sport between being “respectable and mainstream” while maintaining its “anti-authoritarian” identity — specifically naming “We Smoke Weed” as an example — brought to light that the sport was growing large enough to be noticed. And, not only was it being noticed, but the way it was perceived by the outside world impacted opportunities to play and grow the sport.

With the move to expand youth ultimate in 2002, there was now a specific UPA goal which conflicted with the long implicitly held values of free expression and player responsibility. Offensive or inappropriate team names, particularly of high-profile teams, had the impact of lowering the sport’s credibility or turning parents or school administrators away from the sport — people whose support we needed to be able to grow the sport effectively at the youth level.

In 2005, the UPA for the first time forced a handful of teams to change their names. Those teams included “Jailbait” (a HS Girls Team), “UFUCT” (the University of Florida men’s team), and “Whoreshack” and “Meth” (National-level mixed club teams out of Oregon and Iowa, respectively). As a relevant aside, shortly after the forced name changes, the UPA staff and some friends went to a small, local tournament under the name “Jailbait Whores on Meth” with “UFUCT” written on the jerseys. The implicit message was that the profile of events was relevant when determining the acceptableness of names.

Around the same time, language used by players on the field and sidelines became a bigger issue for similar reasons. As the sport was attracting more non-players from a variety of backgrounds, the UPA recognized that player behavior, particularly as far as language goes, had the potential to impact people’s initial perceptions of the sport. I recall one PE teacher writing to me around 2005 who had been to Michigan College Sectionals. She had been interested in bringing her students to watch but there had been so many “f-bombs” that she didn’t feel comfortable doing so. While this was long before USAU instituted TMFs for cursing (later classified as Technical Fouls), I did write an article for the Winter 2005 UPA magazine appealing for players to recognize that their language and behavior had the ability to impact and harm the goals of the sport and its players.

Coach Certifications

IN ORDER TO facilitate the growth of youth ultimate and manage the growth of coaches at all levels, in 2004 the UPA began a new coach certification process. The certification program hoped to achieve two things: (1) accelerate the development of coaches to manage the growth of the sport and (2) ensure that the player-controlled nature of the sport continued as this new, authoritative role grew within the sport.

On the face of it, particularly in retrospect, the idea of a coach certification program seems obvious. But the program did challenge some fundamental philosophical ideas about the sport. Formalizing what had essentially been an informal role and interjecting the governing body into a relationship between teams and coaches was not met with universal acceptance. The program began at first as a voluntary program in which the certifications were not required for any purpose. Soon after, however, the UPA began requiring coach certification for US National Team coaches and to be allowed on the sideline of games where access was restricted (This mostly applied to bracket games at the College Championships at the time).

Resistance to these requirements was loudest from long-time, highly experienced coaches who believed that their experience should exempt them from certifications. The certifications also required a background check and there was resistance from coaches who did not want to give their personal information to the UPA or who had background checks done already for the institutions for which they were coaching.

Resistance to these requirements was loudest from long-time, highly experienced coaches who believed that their experience should exempt them from certifications. The certifications also required a background check and there was resistance from coaches who did not want to give their personal information to the UPA or who had background checks done already for the institutions for which they were coaching.

The UPA held firm on both counts, requiring even long-time coaches to become certified and instituting background checks for all. While some could argue that this new program was creating a barrier to entry for coaches — in opposition to the desire of players to have more coaches — there was a reasonable argument to be made that these requirements were for the good of the players by ensuring that coaches were reputable, establishing and communicating coaching standards, and creating a mechanism by which to adjudicate potential violations of these standards.

All of these early forays into managing the increasing complexity of the sport in ways that brought the individual desires of players into conflict with the general will of the membership for the direction of the sport were validated in the 2006/7 strategic planning process. That process provided an opportunity for players to express their frustration with any of these new policies around censorship, alcohol, coaching, and beyond. Few did.

Strategic Planning Based Changes

THE UPA INTRODUCED many changes that impacted the player experience during the years following the 2006/7 strategic planning process, most of which were implemented between 2007 and 2011. Among these changes were increased uniform requirements, increasing investment in observers, the college restructure, roster limits for club teams, expanding the number of HS Regional events, restructuring of open masters and introduction of grand masters and women’s masters.

These changes, by and large, were based in what the membership wanted as conveyed during the 2006/7 strategic planning process and were all outlined in that Strategic Plan. While there were some rough spots in the implementation of some of these (notably the conflict with Cultimate which accelerated the timing of the college restructure), these changes were accepted if not welcomed by the membership. At the very least, the organization has been able to point to a robust set of available data that supported these changes. It wasn’t until the later part of that strategic planning period, when the organization began diverging from the strategic plan, that the disconnect between USAU and the membership resulted in changes impacting the player experience that lacked deep player support.

The US Open & The Triple Crown Tour

THE CREATION OF the US Open was the first real indication that USAU was putting its own vision of the sport ahead of the membership’s. One of the major topics of discussion during the 2006/7 Strategic Plan had been the UPA’s role internationally. Some on the Strategic Planning Committee at the time argued that the UPA should broaden our governance and consider hosting international events with the possibility of becoming the International Governing Body. This position was taken due to what was seen as weak leadership at the time by WFDF, as well as feedback from foreign players during the strategic planning process (from surveys and interviews) that indicated that there was a demand from top foreign teams for opportunities to compete in the US.

On the other side were those who argued that our membership did not express a significant interest in growing international play or having more international opportunities and that a focus there would take away from the many very clear goals of the membership. This view was bolstered by concerns that we might risk the privileges of being the official National Governing Body of the sport, such as choosing the national team, by turning our attention to international organization. This group argued for supporting WFDF’s growth — financially and through expertise — and not hosting any international play. That argument won the day.

On the other side were those who argued that our membership did not express a significant interest in growing international play or having more international opportunities and that a focus there would take away from the many very clear goals of the membership. This view was bolstered by concerns that we might risk the privileges of being the official National Governing Body of the sport, such as choosing the national team, by turning our attention to international organization. This group argued for supporting WFDF’s growth — financially and through expertise — and not hosting any international play. That argument won the day.

The final strategy of the 2007-2011 Strategic Plan was “Align with and Support Other Organizing Bodies (e.g. WFDF) in order to Facilitate International Growth” and included two tactics:

- Tactic: Partner with WFDF in order to implement a strategic thinking process for international growth.

- Tactic: If warranted and requested make targeted investments to build the organizational capacity of a select number of international governing bodies to support growing the sport of Ultimate internationally.

The decision to create the US Open directly contradicted the Strategic Plan in place at the time. The process of deciding to create the US Open is barely discussed in the 2011 Summer Board Meeting notes, and discussions with Board members at the time provided no additional information on how or why the decision was made. Because this is such a critical juncture in the organization’s relationship with the membership, here are the full notes on the discussion from the meeting minutes:

US Open – Tom Crawford

The concept is that we create and own the marquee event in the world for the sport of Ultimate. We welcome the world to the US for a week long celebration of Character, Community, and Competition. We host interaction and events at all levels. Itʼs hosted in an area that is a vacation destination. The event could help with our sponsors, give us a week long celebration of our mission, and become profitable. We need to announce the event soon.

We want to create an event that brings us together for more than just competition. Showcase the sport like itʼs never been showcased before. The location is critical.

Straw poll on if we feel comfortable announcing this next week. In favor: 12

There is no discussion in the meeting minutes about the fact that we had decided not to host international events in the Strategic Plan. There is no discussion about the fact that one of the major tactics of the Strategic Plan was restructuring the club competition and the US Open would put a major limitation on options for restructuring the division and make a “regular season” more difficult when one of the major events included international teams. And there is no discussion about the weekend of July 4th being a major weekend for “elite” players to participate in core community events including Potlatch (Seattle, WA) and MARS (Pittsburgh, PA) or to engage in non-ultimate holiday festivities with friends and family.

As mentioned, one of the primary strategies of the 2007-2011 Strategic Plan was “Make Significant Changes to the Championship Series that Provide Increased Playing Opportunities and Exciting Events to Showcase the Sport” with tactics that included:

- Plan and pilot UPA Club Pre-Series (Regular Season) Competition Program

- Redraw Sectional/Regional Boundary and adjust Bid Allocation system to support competition and organizational goals.

- Create detailed plan to implement Division II Club Series.

On the table was the potential complete restructuring of the Club Division. While we would still have a National Championship, everything else was set to be a blank slate. But the creation of the US Open took that blank slate and immediately filled it with a defined event that the rest of the restructure would have to work around. During the restructuring process, I spoke to one of the Club Restructuring Committee members who described the US Open as “putting the cart before the horse.” The US Open significantly limited opportunities for a standardized regular season by creating an event with international teams that would only compete at that one event.

On the table was the potential complete restructuring of the Club Division… The creation of the US Open took that blank slate and immediately filled it with a defined event that the rest of the restructure would have to work around.

The introduction of the Triple Crown Tour as a regular season format for Club ultimate marked a significant change in the relationship between USAU and teams which competed in its structure. The addition of a formalized regular season — which included the hastily approved US Open — now dictated when and where teams at many levels had to compete and thus travel. This took control of costs and commitment out of players hands.

The first iteration of the Triple Crown Tour would have required Pro teams to participate in three USAU-determined events, Elite teams to participate in at least two predetermined events, and Select teams to participate in at least one. Furthermore, teams were expected to commit to their Flight requirements before any tournament dates or locations were announced. This decision was met with, at best, “mixed” reactions from both the elite and non-elite ultimate community. After months of both overt and behind-the-scenes lobbying from team leaders to reconsider the new requirements, USAU scaled back the TCT to its current form before it even began. This lobbying also prompted the establishment of a Club Working Group that included elected player representatives to weigh in on any similar competition-related decisions in the future. Even in it’s current form, the Triple Crown Tour only appears to have tepid acceptance or outright resistance from the players.

Teams are forced to choose between competing within that structure or disbanding nearly entirely (no more than six players could compete together the following year), a choice has led directly or at least contributed to a number of teams — including The Ghosts (2015), Robot Twoniraffapus 3030 (2015), and Raleighwood (2016), some national caliber, that likely would have otherwise continued playing together without those requirements — disbanding.

New rules were also put in place that put restrictions on teams from changing their team names. The purpose of this requirement is to help in long-term stability — and thus, branding for “visibility” — but was another way in which the new TCT inserted the USAU into the player-team relationship.

Many players were also upset by the timing of the announcement of the club restructure. Many of the changes were announced only days before the 2012 USAU Club Championships which would determine team’s flight status for the following year. Beyond the substance of the changes themselves, the timing of the communication meant that the rules of the game were essentially changed mid-Series.

The US Open and the resulting Triple Crown Tour (as well as the timing around the announcements) are prime examples of how reduced player influence has impacted decisions, causing programs to fall short of — or perhaps even directly contradict — membership’s desires.

ESPN & Club Nationals

USAU’S CONTINUED FOCUS on “visibility” and the greater influence of non-players on USAU decisions — including its non-endemic media-partners like ESPN — has led to several changes to the crown jewel of the sport, the Club National Championships, that could be described as “not in the best interest of players.”

Many of these changes began in 2013, the year that USAU first moved the Club Championships out of its long time home, Sarasota. Sarasota was very much a player’s destination. Plush, well-maintained grass fields, warm (if sometimes windy) weather, and nearby beaches with varied, attractive housing and entertainment options provided event participants an all-around fantastic tournament experience.

In 2013, the event was moved to Frisco, Texas, and this year it will be held in Rockford, Illinois. The field site in Frisco included a mix of well-maintained grass and much-less-fun turf fields, but included a well-sized finals stadium to help with professional looking broadcasting. Top Golf notwithstanding, the amenities for players outside of the field site were far worse than Sarasota. Outside of the increase in broadcasting opportunities, the Frisco player experience was a major step down from the player experience of Sarasota.

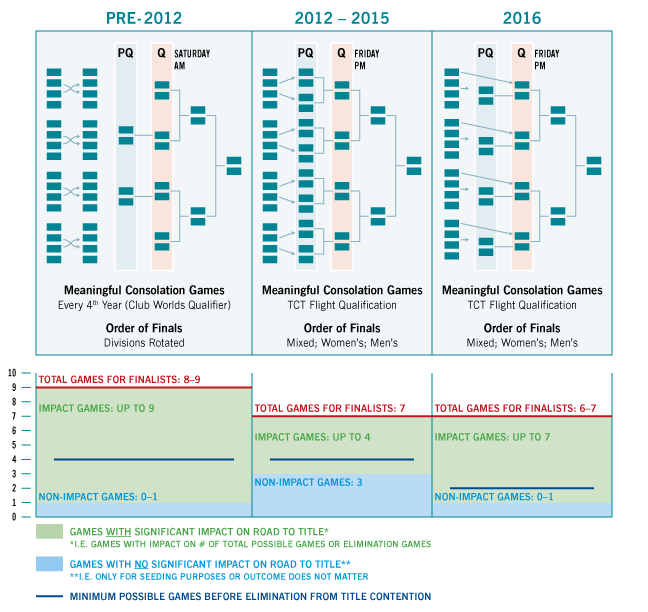

2013 also heralded the reformatting of the Club Championships from a player-supported format that included pools, power pools, and up to four bracket play games for teams to a more broadcast-friendly format that went straight from pool play to pre-quarters for all teams. The old nationals format provided/required eight to nine games for teams playing in the finals while the new one requires only seven.

Perhaps more importantly, the altered format has minimized the importance of pool play games as every team moves straight to pre-quarters. Instead of playing 5-6 games meaningful games over the first two days of Nationals just to qualify for a Saturday of two straight intense elimination games, teams now had little incentive to give maximum effort in any of Thursday pool play games before automatically entering a bracket that now spread competitive elimination games across more days. While the more single-game format across Saturday and Sunday was far better from a broadcast standpoint, it had greatly reduced the number of meaningful points for players paying for their own costs and taking days off of work or school to compete. It also fundamentally altered the way teams could approach competitive decisions throughout the National Championship tournament.

Critically, these changes again were announced just weeks before the tournament took place. Teams that had built rosters and teams for one set of rules now faced a different set.

This format has been changed for 2016, but at the expense of total games for pool winners and losers. Now pool winners only have a maximum of six games to win a championship while pool losers are out of the tournament after three games. The pre-2013 format allowed even 0-3 pool losers a shot at qualifying for pre-quarters should they perform well in their second day pools. And while there were some meaningless games possible in the pre-2013 format, they were rare.

Related to this change in format was how long teams were alive within the tournament. In the pre-2013 format, half of the teams in each division (8 of 16) still had their championship hopes alive on Saturday morning, Day 3 of the tournament. Now, half the teams are eliminated from the championship after just one game on Friday.

For an event where players are footing their own travel and event costs that can exceed over $1,000/player and taking time off work, this effective shortening of the event gives players much lower bang for their buck. Furthermore, before the Club Working Group advocated in 2014 for additional consolation games to be scheduled for Saturday, all but four teams per division had seen their tournament experience limited entirely to week days, with no competition whatsoever over the weekend.

The format changes and the drive for visibility have had an impact on gender equity as well. In the pre-2013 Nationals, USAU rotated the order of the finals between the three divisions (Men’s, Women’s, and Mixed). Beginning in 2013, the schedule became consistently Mixed, followed by Women’s, followed by Men’s. While the viewership numbers or USAU’s broadcast partner’s recommendation might provide a justification for this schedule, the weighting of viewership so highly implies a tacit decision to value visibility over gender equity.

Visibility & Personal Responsibility

BEYOND THE FORMAT and the schedule of Club Nationals, there have been other decisions made that have had a notable impact on the playing experience or have come at the expense of other values or goals of the sport.

USAU has required more teams change their names — some that were not as obviously offensive or injurious to the sport. The required name changes that produced the loudest membership consternation were the 2013 name change for Heva Havas and the 2014 name change for the Ghetto Birds.

USAU has required more teams change their names — some that were not as obviously offensive or injurious to the sport. The required name changes that produced the loudest membership consternation were the 2013 name change for Heva Havas and the 2014 name change for the Ghetto Birds.

USAU has also instituted rules around language usage, issuing Technical Fouls5 for language by players or coaches that is deemed offensive. Again, the reasoning for this decision is visibility for the sport: ensuring that the sport is perceived a certain way and allowing media to capture our sport in a more intimate way than other sports often allow. That decision, however, particularly the strict and top-down way it has been implemented, comes at the expense of a part of our historic culture of player responsibility.

Of course, this conflict was brought into stark relief when an observer issued a TMF for language to Johnny Bravo’s Jimmy Mickle in a critical moment of an elimination game at the 2015 Club Championships. The technical foul had a non-trivial impact on the outcome of the game and shed light on the concessions players and USAU have made to achieve the goal of visibility; concessions that even include valuing visibility over having a game decided by how good teams are at playing ultimate.

Jimmy Mickle swearing technical

USAU has also reduced player control on the field by giving increasing responsibility to observers. Observers now have the right to issue Team and/or Player Misconduct Fouls for violations that go uncalled on the field. This policy allows observers to proactively insert themselves into games without player initiation. The goal of the policy is greater standardization, again for visibility purposes. But the policy is another one where visibility has trumped a long-held value for the sport, its players, and USAU.

Finally, USAU has made decisions to promote the sport’s visibility over players basic understanding of the rules and safe play. In Fall 2015, USAU led off a highlight reel with a clear dangerous play from Club Nationals. For a sport that puts a high amount of responsibility on players to know and understand the rules, promoting plays that undermine that understanding risks our foundation of self-officiation. Placing the value of visibility over rules knowledge and safe play is against the best interests of the players and sport and, if USAU’s goal is a visible self-officiated sport, it’s against their own best interests as well.

Club Series Move

AT THE BEGINNING of this year, USAU proposed moving the timing of the fall club series to the summer — though the idea had been hinted at by USAU for years. This proposal was roundly rejected by the members. The idea of moving the club Series to the summer has been floated by the organization for the past few years with the goal of moving Club Nationals to a time on the calendar with fewer high-profile sporting events to decrease competition for media coverage. The proposed move was another in the series of changes justified by the goal of “increasing visibility of the sport.”

Just a few weeks before voting on finalizing the decision, USAU released a survey to gauge membership’s response to the proposed move. The negative response to the proposed move was overwhelming with members citing several harmful impacts of the move, including:

- Increased conflicts between players participating in club and providing support (coaching, tournament directing, etc.) for the youth and college divisions

- Increased conflict between competitive club play and recreational leagues and tournaments

- The harm caused to northern teams by moving tryouts and early season play into months with high probability of bad weather

- Increased conflicts for college players participating in the club series that could potentially hollow out the lowest level of club competition, reducing development opportunities for college and club players.

The proposal prompted editorials opposing it, a change.org petition that received over 1,300 supporters, and, in the one question on the survey that asked for players preference, well over 80% of players expressed a preference for keeping the Series in the fall with hundreds of members taking the option to write out longer thoughts to express their insistance that the Series stay in the fall.

The statement made clear that member feedback now and in the future about such a move would not be the primary factor in their decision to implement such a change.

Following the outcry, the Competition Working Group made a recommendation that the Series not be moved at the Winter 2016 Board Meeting and the Board agreed with 8 votes for, 0 against, and 4 abstentions.6

USAU released a statement after the vote that explained that the series was not moving in 2017. But the statement made clear once again that “increased visibility” was the organization’s most important goal, that no decision has been made beyond the 2017 season, and that they still perceive this move to be in line with the strategic plan. In the statement they wrote:

“The primary reason for considering such a change is to better achieve the most important goal in the organization’s strategic plan — to increase the visibility of ultimate. Although USA Ultimate has made significant progress towards this goal, the current timing of the National Championships puts the sport at a disadvantage from a visibility and awareness perspective.”

And

“For a variety of compelling reasons, including those mentioned above, the ultimate community (both current members and alumni, athletes, coaches, team managers, event and league organizers, observers, parents, fans, volunteers, staff and board members) has expressed a desire for increased visibility.”