chievement can be measured a number of ways: titles, accolades, and records are all standard means to convey success. But it’s possible that nowhere in ultimate has a record of failure led to so much success as in the case of Mike Payne. Making it to the College National Championship Game as a player three times is an achievement few can claim. But losing all three times? Now you’re in even rarer air. Now you’ve suffered the same fate as Revolver head coach Mike Payne.

chievement can be measured a number of ways: titles, accolades, and records are all standard means to convey success. But it’s possible that nowhere in ultimate has a record of failure led to so much success as in the case of Mike Payne. Making it to the College National Championship Game as a player three times is an achievement few can claim. But losing all three times? Now you’re in even rarer air. Now you’ve suffered the same fate as Revolver head coach Mike Payne.

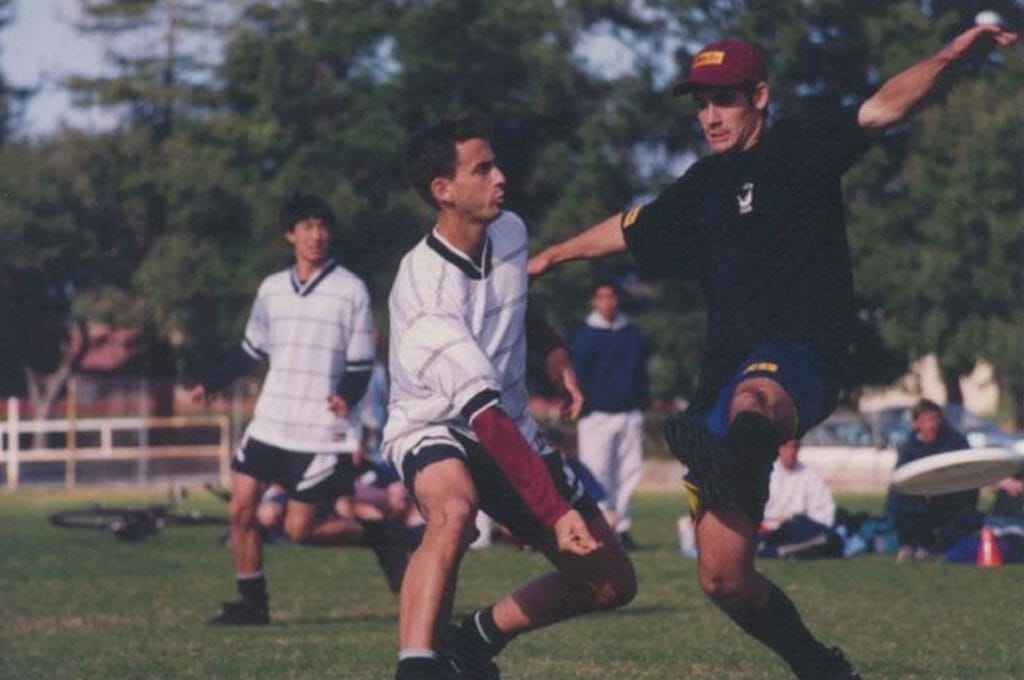

Payne’s Stanford Bloodthirsty teams made it to the final game of the college season three times in the 1990s but could never achieve their goal of a national title. Payne calls himself jokingly — yet bitterly — the “Jim Kelly of college ultimate.” Despite those very real scars, when you dig deeper into all of Payne’s accomplishments since leaving Stanford, it’s clear he has not let those losses define him, but have instead fueled him to bend the arc of ultimate ever upwards.

MIKE PAYNE’S STELLAR career at Stanford was not his first introduction to the school. He was born into Stanford, literally. He was born at Stanford Hospital, three doors down from the office he would occupy two decades later as a Master’s student.

He, like many of us, did not think about playing ultimate until he arrived on campus. Payne touts himself as a “pretty good athlete” when he was younger, who gave serious consideration to attending Willamette University to play D-III basketball.

His brief first exposure to our sport came in high school, at a pickup game with another famous alumnus of the game: classmate and long-time soccer teammate Jason Seidler (UCSB, Condors, and as of 2016, the MLU’s SF Dogfish). But ultimate didn’t infect him at that point, and he did not immediately join Bloodthirsty when he arrived at Stanford. As a freshman, Payne was on the crew team, but the fact that he was not 6’4”, plus the influence of a fellow intern at a health software company, led him away from the 8-man shell and onto the 7-man line. By sophomore year, he had made the switch.

Payne would go on to play Bloodthirsty for five years, including two years while in grad school. His losses were few in his college ultimate career, but his most defining losses came in the national finals in 1997 and 1998. In both games, Stanford lost to UCSB Black Tide, by scores of 21-13 and 20-17 respectively. Those losses gutted him, not just because they were to Seidler’s UCSB, but Payne felt personally responsible, letting other veteran players down.

“I tried to do too much – I should have spent the season helping to develop my teammates and instead I fell into the trap of allowing the team to count on me too much.”Mike Payne

“Back then,” Payne says, “the general view was that star players won championships. Those years, UCSB had more true stars than Stanford. It wasn’t because Stanford didn’t have the athletes, it was because we did not invest in player development to build a deeper roster.”

Speaking about the 1998 final, Payne laments, “I tried to do too much – I should have spent the season helping to develop my teammates and instead I fell into the trap of allowing the team to count on me too much.” That sentiment eventually developed into a team-building philosophy. It acted as the basis for winning ways of the future, when Payne coached Stanford’s legendary run in 2002 and later, playing and coaching Revolver.

MIKE PAYNE STARTED playing club ultimate in 1995 with El Camino, a team made up of Stanford players and teammates. At that time, the Bay Area men’s scene was dominated by a team called Double Happiness, but Payne felt he was still too early in his career to play up with that squad.

The following season, elements from El Camino — including Payne — established a feisty, young team called Saucy Jack. Almost immediately, there was no love lost between the upstart team and Double Happiness. That year at Regionals, Saucy Jack pulled off what seemed to be an impossible upset of their local rival to claim a bid to Nationals, eliminating the Bay Area favorite from the Club Series.

That victory proved to be another formative moment for Payne, showing him that a young team of unknowns had a chance against even a juggernaut if they approached the game in the right way. It was a lesson he would return to a full decade later.

After two years of the Saucy Jack-Double Happiness rivalry, the leadership of the two teams decided to merge, forming Jam. Payne was a captain in Jam’s first year and a top player at that time, helping to bring about a new era of Bay Area dominance with this newly-established team. Jam would qualify for Nationals as the top team out of the Bay in seven of the next eight years, reaching the national semifinals five times.

The rise of Jam coincided with the emergence of another Bay Area powerhouse: Fury. The now famous women’s program won their first club title in 1999 over another dominant northwest team in Portland’s Schwa, kicking off a run that continues to present day, with a total of nine National Championships — a record matched only by Boston’s Lady Godiva.

Jam and Fury’s success on the field was matched by their ability to have a good time off the field, frequently partying together. It was in that setting that Payne’s budding relationship with another prominent ultimate player, Fury’s Samantha Salvia — Sam to those who know her in the ultimate community — began.

Mike and Sam hit it off during one of these Jam-Fury parties, and an ultimate union was established. Sam says that it was to some degree luck that she wound up meeting Mike. A Rhodes Scholar at Oxford, she took time to study at Stanford, and as a former D-I field hockey player, had an urge to compete again. She wound up on Superfly, captaining them to the 1999 UPA College Championship, and progressing to Fury near the beginning of one of the most successful ultimate programs — men’s or women’s — in the sport’s history. She would go on to win several championships with the team she now coaches.

Sam says her relationship with Mike early on was “smooth,” but there was one thing she was able to hold over Mike for years: scoreboard. The Trophy Mantle early on between the two athletes displayed Sam 2, Mike 0. The Mike Payne Championship drought wouldn’t last long, though Sam’s got the edge still to this day. Mike and Sam eventually married in 2005, and of course, he proposed by throwing her a disc with the engagement ring attached to the bottom… on a Costa Rican beach.

With his upstart Jam team making waves in the Club Division and his relationship with Sam in its infancy, Mike Payne’s future heading into the new millennium was bright. But it would not be all smooth sailing.

Everyone’s gotten hurt playing a sport. Some get injured, and either time, or surgery, can get them back on the field. In 1999, for 25-year-old Mike Payne, it was a lower back injury and subsequent major surgery that changed the trajectory of his path to ultimate’s peak. Sam was with him when he went to the hospital for surgery. She laughs recalling meeting Payne’s parents for the first time in the ICU. They shook hands over Payne’s body just as he was emerging from general anesthetic.

That injury would rob Payne of approximately two years of his playing prime, but he says it did allow him to see ultimate from a different perspective — and that vision led him to a new role in the sport: coaching Bloodthirsty.

IN 2002, HAVING recovered mostly from surgery, Mike Payne could finally call himself a National Champion… as a Coach. He didn’t play a minute for the Stanford team that took down the Wisconsin Hodags 15-5 in the final college game that season, but his playing experience in past finals had a big influence on his coaching philosophy. As he had learned in his own Bloodthirsty days, he was convinced that the star-player model had little future, and set out while coaching his alma mater to “right the wrongs” of what he thought was an out-dated model of team construction.

Payne says the 2001 Stanford team was top-heavy, like his old teams were. That year, his first as a coach, he focused on player development for the middle and bottom of the roster. But, that meant shifting the roles of top players, which often spells early turmoil. In 2001, he leveled with his players. “We can either win some games this year and some games next year, or we can LOSE a lot of games this year, and win Nationals next year.” As a team, they decided on the latter.

The 2002 Stanford team was famously known as “The Faceless Army,” a testimony to Payne’s focus on players contributing across the roster. In correcting the star-player “wrong,” he clearly did something right, as Stanford won Nationals convincingly that year. The team lost only one game in the regular season, and is still considered one of the greatest college teams of all time.

How that Stanford team won, and how it was assembled, was the foundation upon which Payne’s next project would be built.

PAYNE TALKS ABOUT the surgery that sidelined him with thoughtful reflection and reverence. “It helped with my maturity,” a more senior Payne reminisces. “I spent a lot of time on the sideline, watching the approaches of other teams, which helped me deeply understand ultimate strategies, both proactive and reactive. But it was certainly a difficult time – I was worried that the injury was stealing the best years of my career.” It would be another four or five years before Payne truly understood how this fear would become a reality.

“That win at 2006 Regionals was really the foundation for the program you see today… it showed us the power of the Revolver model.”Mike Payne

We all slow down eventually. Of course, it doesn’t feel like we’ve lost a step, but then you go to chase down a huck from 45 yards… and you’re outrun by that one kid on the other team, who you totally had beat. It doesn’t happen overnight, and for Payne, it wasn’t until a fateful spring day when he realized something changed. In 2006, he was cut from Jam.

In retrospect, he says he probably had misperceptions about how good he was at the time. “I had a lot of hubris. My injury and surgery definitely knocked me down some pegs. I was definitely no longer a top player. But, I didn’t really see it until being cut by the team that I had helped form eight years earlier.” With the benefit of 10 years of hindsight, Payne now admits, “I would have cut me, too.”

Perhaps being cut from Jam was fate. Payne considered retirement, but a few weeks later, he learned some former teammates were forming a new program. Nick Handler (who Payne coached on the ‘02 Stanford team), Chris McManus, (an old Jam teammate), and Marc Weinberger (a former Saucy Jack/Jam teammate), came together to form a new Bay Area team called Revolver. This program would focus on a mix of young and old. They wanted to play as friends, commit to Spirit, get better with every game and practice, and build great players from local schools. The team agreed not to focus on or talk about winning, a principle Revolver holds to this day.

This mentality came as a response to Jam’s outlook, where expectations of winning were met with mounting pressure when the championships didn’t come. Payne says that Revolver “seemed to be the program that I had hoped to build when Jam was formed… but this time I had the benefit of experience and a group that checked their egos at the door.”

But, that positivity and enthusiasm was clouded. Payne, along with some other Jam rejects who found themselves instead building with Revolver, were motivated intensely by revenge. Jam had renamed themselves Justice League for the season and defeated Revolver in their first two meetings at Labor Day and then Bay Area Sectionals. The teams would meet again in the elimination bracket at Northwest Regionals, with Revolver taking an 11-8 victory and Payne finally claiming his just revenge.

Revolver’s win over Justice League at Regionals in 2006 was as shocking as Saucy Jack’s win over Double Happiness ten years prior. Not only did this win keep Payne’s former team from a trip back to Nationals, it was the first time since the 1998 merger that Jam did not finish the season as the top Men’s team in the Bay Area.

“There was some kind of cosmic justice at play that year,” Payne suggests. “I certainly think I learned some things ten years earlier with Saucy that helped Revolver in 2006. That win at 2006 Regionals was really the foundation for the program you see today… it showed us the power of the Revolver model.”

That year, Revolver’s first as a team, they captured a 5th place finish at Club Nationals. It wouldn’t be until 2010 that Revolver won it all — the only time Payne would win a championship as a player. But like the Stanford teams in 2001 and 2002, Revolver was built early on to experiment first, and succeed later.

IT WAS ALSO around that time that the saplings of the current state of ultimate — the sport as a whole — were taking root. Running parallel to his Stanford-Jam-Revolver timeline, Mike Payne aerated the soil, planted a couple seeds, and poured a lot of effort into the future of the sport.

In 2002, Payne began working on a project for the Ultimate Players Association, working with Will Deaver to brainstorm and research potential structures for tiered play, similar to other sporting competitions like European soccer’s promotion-relegation structure. These casual discussions between the two would lay the groundwork for what we now have in the Triple Crown Tour.

Based on this early work with Deaver, Payne took an interest in the sport’s governance. In 2004, he was first elected to the Board of Directors, a position he’s held on and off since, even serving as the Board’s President for six years — the longest-serving President in the organization’s nearly 40-year history. While on the Board, Payne has worked with the staff and other Board members to drive rapid change and growth, including:

- Changing the organization’s name from the Ultimate Players Association to the much more marketable — albeit not entirely uncontroversial — USA Ultimate.

- Placing emphasis on youth and High School ultimate, expanding staff to work on these programs.

- Growing membership from about 19,200 participants in 2004 to about 50,000 in 2015.

- Earning official recognition from the IOC and USOC.

- Securing the sport’s first broadcast agreement with ESPN.

- Creating and implementing the Triple Crown Tour.

Henry Thorne, who also sits on the Board at USAU, notes that the same preparation and attention to detail that made Payne a success on the field translates to the Boardroom. “I’ve played against Mike in fun games and tournaments, and his mark was so precise and tailored to my throwing style, that it prevented me from making any throw I was attempting.” Much like the precision necessary to be a winning ultimate player, the details are essential when running a sport’s governing body.

“Mike is a super-skilled manager and a great leader, and USAU is probably twice the organization it would have been… had he not served.”Henry Thorne

There is however, a contingent of dedicated ultimate advocates who see some of Payne’s contributions to the sport as contradicting the inclusive way he has approached playing and coaching. According to Kyle Weisbrod, Head Coach for UW Element in Seattle and also a former USAU staff and Board member, the development of the organization’s current Strategic Plan is an example of this.

In 2006, when the UPA was crafting their first ever Strategic Plan, there was an intense discussion of the organization’s role in the global sport of ultimate, and the organization’s relationship to WFDF. Weisbrod says a large group wanted to support WFDF but Payne wanted USAU to lead the future of the sport on a global scale. Ultimately, the board decided to stay focused domestically, in line with the opinions of the majority of membership who weighed in during the strategic planning process. However, the creation of the U.S. Open as an international tournament built into USAU’s club season, specifically contradicted the priorities laid out in the strategic plan.

Board member John Terry, elected to the board while still in college, added that while in his estimation Payne’s passion is “special,” he questioned at the time “are we [USAU] ready for a US Open?”

Weisbrod claims the inclusion of the US Open in 2010 was “indicative of strong-arm leadership of what membership doesn’t want.” He believes this same brand of leadership was apparent in a far less inclusive strategic planning process in 2012, which resulted in the current plan that emphasizes visibility over the playing experience of current members. Disagreements have come to pass in board meetings, and Weisbrod said that Payne’s contribution to USAU has made the organization more corporate, for better or for worse.

Thorne sees Payne’s contributions to the Board and the sport as a clear positive. “Mike is a super-skilled manager and a great leader, and USAU is probably twice the organization it would have been… had he not served.”

PAYNE’S TIRELESS WORK towards team goals speaks to who he truly is, according to longtime friend, former teammate, and co-founder of Omada Health, Adrian James. Payne is currently the Chief Commercial Officer and Head of Medical Affairs at Omada, a company that is bringing together clinical psychology and technology to prevent diabetes and heart diseases, conditions for which 150 million Americans are at risk. Omada is a small, fast-growth company with 250 employees and counting — of which, Payne oversees about 50 — which is emerging in the healthcare sector.

James says at Omada, Payne has ambition written on his sleeves, passionately fighting for the continued development of the company, and championing Omada’s cause from coast to coast. James calls Payne a dedicated intellectual, and “definitely not a bro,” whose attitude and vision have helped develop a small health-tech startup into a nationally-recognized health provider.

James played ultimate with Payne at Stanford, and said even at the age of 18, he could tell that 20-year-old Mike Payne was more mature than anyone on the team. James hails Payne as a leader among leaders, operating in service of shared team and company goals.

Payne’s time as a coach, in its successes and its failures, has seemingly taught him lessons on how to manage people in any setting. James recalls noticing Payne dial-back his intensity at times when in the presence of others who don’t share his fire in the office. It also means, that when Payne takes on the “hero” role at Omada, like he did when playing for Stanford, his failures cut that much deeper. James says for all of Mike Payne’s intensity, passion, and precision, he’s very sensitive and self-critical.

Payne’s vision for Omada drives him to work incredibly hard, in part because his mother has suffered the debilitating effects of being a Type 2 diabetic for 70 years. James notes that Payne seems to feel comfortable suffering through the tough days as long as the cause is a worthy one in the end.

Given his experience both in coaching Stanford and in playing with Revolver, this is far from surprising.

THE BIG PICTURE has largely served Mike Payne well, but a vision needs a plan. Of all his projects, his wife says, he’s probably most proud of Revolver.

It should be noted, Revolver wasn’t started by Payne, though he was a member of the team in 2006, its first year, and captained the team from 2007-2010. Also, Payne and Revolver haven’t always been together. Payne stepped away from the game as a player after the team’s 2010 championships, and from Revolver altogether for a few years, walking out on top. He decided to focus his time on his family, career, and responsibilities at USAU. He returned to coach the team he once captained in 2013, where he continues in that role to this day.

“He created a true team concept [for Revolver] and he got everyone to buy-in as he set the team’s values.”Robbie Cahill

Revolver’s identity today, and legacy beyond, owes a lot to Payne, according to his players. Payne is immensely proud of his time as Revolver’s coach, winning two National titles (2013, 2015) and one Worlds title (2014) — losing only three tournaments total in the last three years. Veteran Robbie Cahill stresses that the team’s success comes down to two important pieces that really set Revolver apart from other men’s programs, and they’re both thanks to Payne.

First is Revolver’s values. “He created a true team concept [for Revolver],” Cahill says, “and he got everyone to buy-in as he set the team’s values.” Payne helped set the principles of the team, including coining the oft-repeated mantra among his players: “Intensity, Humility, and Discipline.” He has been steadfast in promoting Spirit of the Game, a focus that Payne proudly touts by pointing out that five of the last seven Farricker Awards — given to the men’s division player who exhibits the most spirit and skill at Club Nationals — have gone to Revolver players.

He also helped guide team-development values: balance, with the right players, not just the best ones. Revolver builds on the experience of its veterans and develops the talents of what Cahill calls “projects.” One of those is Cahill’s backfield partner Ashlin Joye, who Cahill said was definitely a project, but is now widely regarded as one of the best players in the game. Revolver certainly isn’t the first ultimate team to employ a balanced look, but what’s separated Revolver so far has been their steadfast resolve to adhere to, and execute this plan.

“A lot of people watch the superstars,” comments Cahill. “But if you look closer, even in the finals of Nationals, it is the guys in the middle and bottom of the roster that are winning games. The more accomplished players on the team do an incredible job of giving those guys the space they need to develop.”

Payne’s second legacy at Revolver is recruiting. There are two ways to look at recruiting: player retention, and bringing new guys in. Cahill told me that in 2007-08 — even as the team hit a brief plateau in its performance and results — Payne’s efforts to keep the team together were unmatched, and once a core of players (including Cahill) re-committed to the team, their success became infectious from the outside.

One example of Payne’s recruiting includes a young, talented Johnny Bravo player who saw what was happening in the Bay Area, and after getting smacked by this group of guys at Nationals in 2009, decided to investigate further.

The way Payne talks about Beau Kittredge says as much about the superstar now plying his talents with the AUDL’s Dallas Roughnecks, as it does about the guy who recruited him. Payne told me his first conversation with Beau was in a bar in the East Bay, and from the first meeting, he knew Beau marched to a different drummer.

Beyond being an immense physical talent, Payne notes Beau’s willingness to buy-in to Revolver’s system — taking on a different, but still vital role in the quest for a national championship. The way Payne and Beau have worked together to structure Beau’s role shows Payne’s vision in its truest form. It’s one thing to go up against a team with just the best player on the planet, but when the best player is also surrounded by nine members of 2016 US National team, you can’t just double-team the tall, fast guy.

“Beau is Revolver’s Tim Duncan,” Payne says. “He could be doing a lot more at any given time, but on Bravo he saw that wasn’t the answer, just like I did at Stanford 18 years ago… I think we are both optimistic that our work together to produce great ultimate, with teammates acting with IHD [Intensity, Humility, and Discipline], is starting to act as an example for the next generation.”

THESE DAYS, PAYNE is approaching his leadership of Revolver from a different angle. With two young kids, a wife busy as a trainer at the Positive Coaching Alliance (yes, Mike and Sam share a lot of coaching ideas at home) and a bevy of responsibilities from Omada to USAU, Sam says he’s finding time to still do it all, but re-configuring his talents to maximize his usefulness at each organization. Cahill also told me Payne’s role with Revolver is evolving, focusing intensely on individual player development, as well as player and team psychology.

“Revolver’s strategies and tactics are largely set; we feel no need to change them. That allows me to focus on my players and help them be better at their roles.” Payne confidently declares, “I don’t think you’ve seen Revolver’s peak yet.”

Omada Health’s future is also looking bright, with the growing success of the company’s “Prevent” program. Payne has brought the same drive to Omada that he brings to Revolver, and is leading the charge to bring the program to hundreds of thousands — even millions — who might otherwise end up with diabetes or heart disease. The company and program have a very personal meaning for Payne with his mother and Sam’s dad, who’s also on the program and has drastically reduced his risk.

On the board at USA Ultimate, Payne’s as busy as ever. You may have read on this site a year ago a back-and-forth between Tiina Booth and Payne over Gender Equity in the sport. He believes that the effort spearheaded by the Gender Equity Ombudsgroup supporters is being met with action inside the organization. He says this push pointed out that there was more USAU could be doing, but added that the goal of the organization is Equity, not just Gender Equity. It’s something he continues to work on with the board at USAU, and those discussions continue into 2016.

And as far as family life, Salvia says that while Payne’s achievements with Revolver have been immense, she’s most proud of his role as a father. Their young kids haven’t yet started to play ultimate, though one was technically on the field when Fury won one of their many championships, and the other was on the field in 2015 when Payne coached Revolver to its fourth National Championship in six years. Rylan (7) and Spencer (4) have grown up a part of Revolver, attending countless practices and tournaments — Rylan even went with the team to a tournament in Colorado as their water boy.

Payne’s been described as fiery, passionate, smart, and visionary. But something more lurks inside, according to those that know him best: Mike Payne’s a softie. He’s a softie for teams, and those who are as willing — as he is — to put it all on the line. He finds deep joy in others’ successes, and hugs his players tight when they win big. The failures early in his career may have left a bit of a chip on his shoulder, but anyone who has lost big and then won can tell you the nectar is that much sweeter because of it.

An article in an October 1997 edition of the Stanford Daily — written after Bloodthirsty’s first loss to UCSB by Jim Tankersley, now of The Washington Post — said this about Payne:

“Payne is the veteran’s veteran, a focused player who loves the ultimate experience both on and off the field… More than anyone, Payne’s fire symbolizes the quest of the team.”

It seems, that fire never left.

Pat O'Brien

More Features

Resources for College Ultimate Frisbee Captains

Resources for College Ultimate Frisbee Captains

Davide’s Doctrines: Vertical Stack

Breaking down central and side vertical stacks with six cutters and one handler.

We Are Not Twins

Australia's Phillips sisters are two of the most important factors in the Firetails' success at WUGC 2016, but they are contributing in different ways. As usual.

From UPA To USAU

Over three meticulously researched parts, Kyle Weisbrod makes the case that the relationship between USAU and its members is at an all-time low and lays out the history of decisions and organizational changes that led to this point.