March 18, 2014 by Martin Aguilera and Sean Childers in Analysis with 0 comments

Harvard Redline currently sits at #7 in the Ultiworld Power Rankings. But are they a #7 team that could upset one of the top dogs, or are they a notch below the elite?

We sat down with game tape and broke down the Harvard offensive performance from Queen City. The lessons of what worked well and what didn’t is useful information — both for opponents and other teams with similar vertical stack issues.

Video analysis shows that Harvard is blessed with great young players, a lack of selfishness, and solid skills down the roster. One big positive was Harvard’s disciplined reset-reverse system, using short passes to create larger yardage gains off upfield swings.

Their downfield cutting system, however, needs to grow if it wants to make an equal contribution for the team offense. Cutters did a few things well, such as boxing out defenders for tough under catches, timing important swings, and getting the disc back to the handlers. Frankly, that’s better than many college teams can do. But flaws on important fundamentals, like crowding in lanes, cutting off of important vertical angles, and inconsistent deep cutting held Harvard back. Some of these issues didn’t hurt Redline in games against less-developed teams at Queen City, such as Iowa and Michigan; nonetheless, they’ll need to avoid reinforcing bad downfield habits if they want to the compete against the more athletic and experienced college teams.

Harvard Offense: The Basics You Need to Know

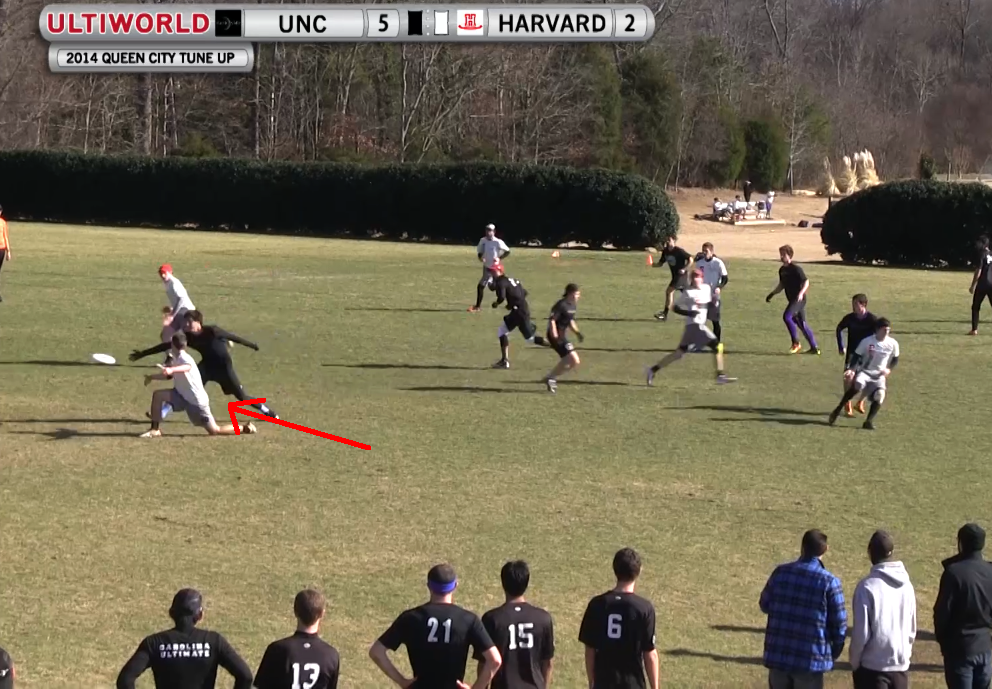

Harvard primarily runs a vertical stack offense with the traditional two handlers back. While U23 team member John Stubbs gets a lot of the attention, the real key is handler Mark Vandenberg. Vandenberg has the athleticism to get open and most of the requisite throws. His really elite skills are a great backhand around break and the mind to know when to use it — and really, when to use any throw:

One of many of Vandenberg’s around backhand breaks on the weekend came in the finals against one of UNC’s top defenders, Ben Snell. For a deeper look at how Vandenberg progresses quickly through his looks, check out this coaching video made by one of the authors.

After Vandenberg and Stubbs, other notable players are Jeremy Nixon (a quick cutter who gets the plurality of under cuts), William Dean (often handles with Vandenberg), and David Reshef (an energetic downfield cutter).

The offense is predicated more on smart disc movement and decisions, with fewer deep shots compared to other vertical or side stack systems. The reset in particular is important; Harvard desperately wants to open up a swing pass after their initial dump, so you will often see the dump setup parallel to the thrower, even on the open side. That is followed by a reset throw into negative yardage space, allowing the reset to run onto the throw, generating separation from the dump defender, and finishing with the swing that reverses the field. This reset positioning constricts the downfield lanes for cutters1 but allows for their reset-reverse system to work more efficiently.

For the most part, Harvard’s backfield footwork is good and they can easily switch this cut into an upline one if the defender overplays the backfield. However, one key to UNC’s final victory was having veteran2 dump defenders who knew when Harvard was all-in on their standard backfield dump. UNC would typically seal the upline cut while maintaining body contact plus sightline of the thrower backfield. That limited the options the reset cutter had. In order to be successful against this style of defense, Harvard’s resets will have to improve their cutting technique and find a way to get a more free release that opens up both the upline and backfield options.

Compare and contrast the separation Harvard dumps had against Michigan (right) to UNC’s more physical reset defense, which generated a few backfield turnovers

Downfield Offensive Weaknesses

Yet much of what kept Harvard from challenging UNC for the Queen City title took place downfield:

- Cutters making sequential cuts into the same space with poor clearing; this created lots of clogging in the same few lanes

- Too little “verticality” on cuts; for example, deep cuts often aimed for the open sideline rather than the back middle (or breakside) of the endzone3

- Insufficient number of pure, 100% cuts and pairings of 100% cuts4, allowing defenders to deny separation

Issue #1: Cutting Into The Same Space:

The earlier clip both highlighted Vandenberg’s great timing as well as one of the systemic issues in Harvard’s offense: They look to attack the same area but don’t clear out well enough to maintain space in those areas.

This is the result of Harvard having not figured out who should be cutting to the changing open space. Often two cutters think they can get open in the space, resulting in neither of them being open and two defenders in the lane. Those defenders can be left as poachers, further limiting the open space Harvard is trying to use. When this happens, Harvard has to swing the disc even more than usual, given the few options in front of the disc.

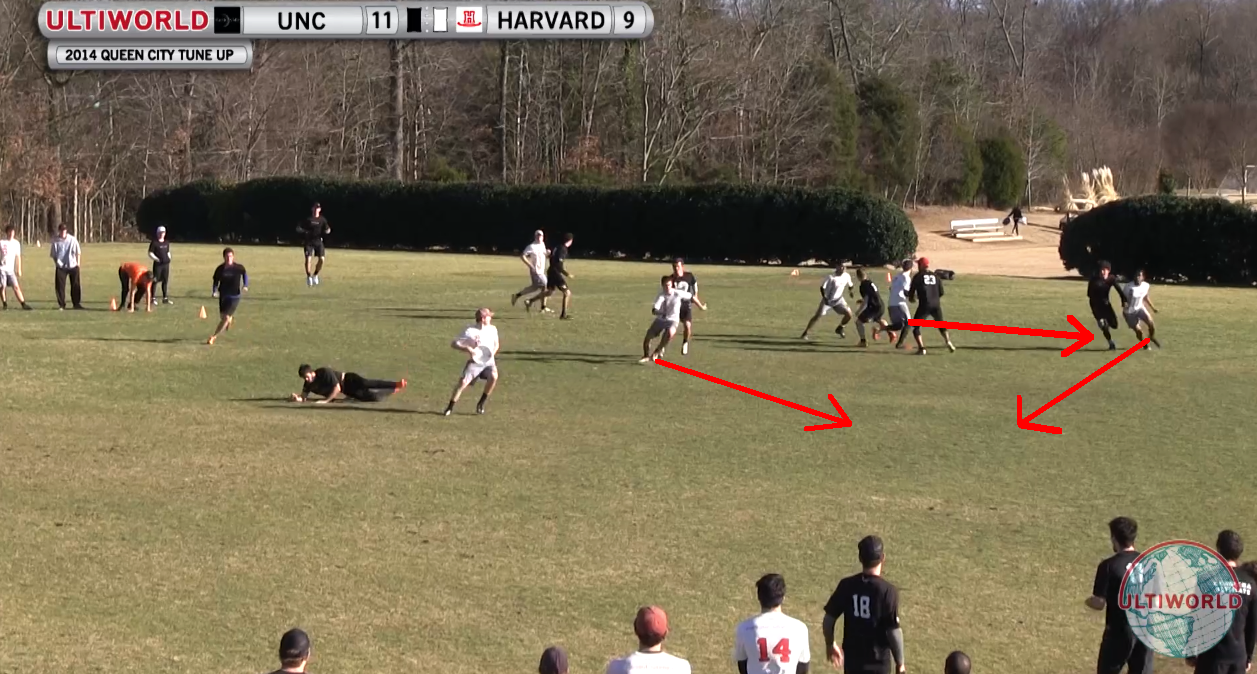

Both the front and back of the stack attack the same space at the same time. In this situation Stubbs (the back cutter) needs to recognize the front cutter and stop his cut. Instead he finishes the cut and is still in the lane one second later when . . .

Both Jeremy Nixon and Mark Vandenberg attack the same space that is now shrunk because of Stubbs’ failure to stop his cut and get back to the stack. The result of this play is a hammer to swing the disc to the break side of the field.

The double and triple cuts were an issue for Harvard’s offense — especially near the endzone. You can see from the clip below that part of the problem is the aggressiveness from Nixon and Vandenberg. Both guys, who carry a lot of the load for the offense, expect permission to cut if their defender misplays them one step too far in the wrong direction.

In the screenshot below, both star players had angles to cut near this endzone. Nixon follows up with a double cut, but other Harvard players think it’s their turn to go based on positioning in the offense. Only one Harvard cutter realizes there’s too much action and cuts off his cut.

Two initial cuts in the screen shot are to almost the same space, followed by three subsequent cuts also crowded around the cone. This is the same issue of over-cutting and clogging that is identified in the sequence of images above.

Issue #2: Cutting Towards the Sidelines:

You might have noticed something else about some of Harvard’s cuts from the clips above: Their cutters tend to have lots of sideline (horizontal) orientation — a sort of flare or screen pattern repeats itself after you’ve watched them enough on video. There’s a time and place, especially in vertical stack offenses, for these types of cuts, but Harvard overdoes it.

[youtube 2zu1hOBTHSw 600 337]

This clip shows why Harvard’s offense can sometimes stall from too many horizontal cuts. Dixon’s (#4) cut, in particular, could have been easier to hit with a break throw if it had more verticality to it. After a reset, Stubbs (#14) makes a cut towards the sideline that would have provided little yardage if hit; #5 attempts a secondary cut into the same space that is even smaller and more occupied now.5

Issue #3: Simply Not Cutting Hard Enough:

[youtube yWHppN9wKYY 600 337]

Stubbs’ initial cut after that reset is one of the systemic problems that Harvard faces with their offense. Their good athletes are trying to make under cuts with a simple, static juke — then a cut to the open space in front of the disc. In the best case they can get a step under their defender then get decent yardage.

However, against better defenses their juke doesn’t work, so they don’t get the inside lane as easily. Harvard’s throwers are smart. They aren’t going to release the disc until the receiver has at least almost broken the line between the defender and the disc. Against better defenses that don’t lose position against a juke, Harvard’s weaker cutters don’t get open at all with this move, and their best cutters (Nixon and Stubbs) require more strides to break the line and get the disc. This results in fewer yards per pass and a slower developing cut.

But Harvard’s downfield cutting problems are more than just too much juking: Harvard’s deep cuts are sometimes too tentative to create either enough separation for the deep cut or divert enough attention from other defenders. They compound this problem by often making their deep cuts also flare toward’s the sidelines, limiting the amount of angle that the thrower can throw into and making a trailing defender’s job easier.

Take a look at some of the deep cuts in the clip below.

[youtube lYKVltCXi0Q 600 337]

Notice how long Harvard’s cutters have their heads up, trying to make eye contact with the thrower and see if it went rather than just creating the separation and looking back once or twice. Often, the cut or the throw is angled towards the sideline rather than straight deep, making it easier for the defenders to know where to catch up and limiting the number of steps they need to recover to get back into the play.

In some games (especially the Iowa game), Harvard was able to score deep even on 80% deep cuts. That makes these deep cuts a great example of the type of habit that can be ingrained and reinforced against certain competition, but comes back to hurt a team when they move up and play tougher competition.

And in some situations, they made harder cuts to more intelligent deep spaces. When Harvard did this, they often forced defensive hesitation and were able to capitalize with solid yardage on the next under cut.

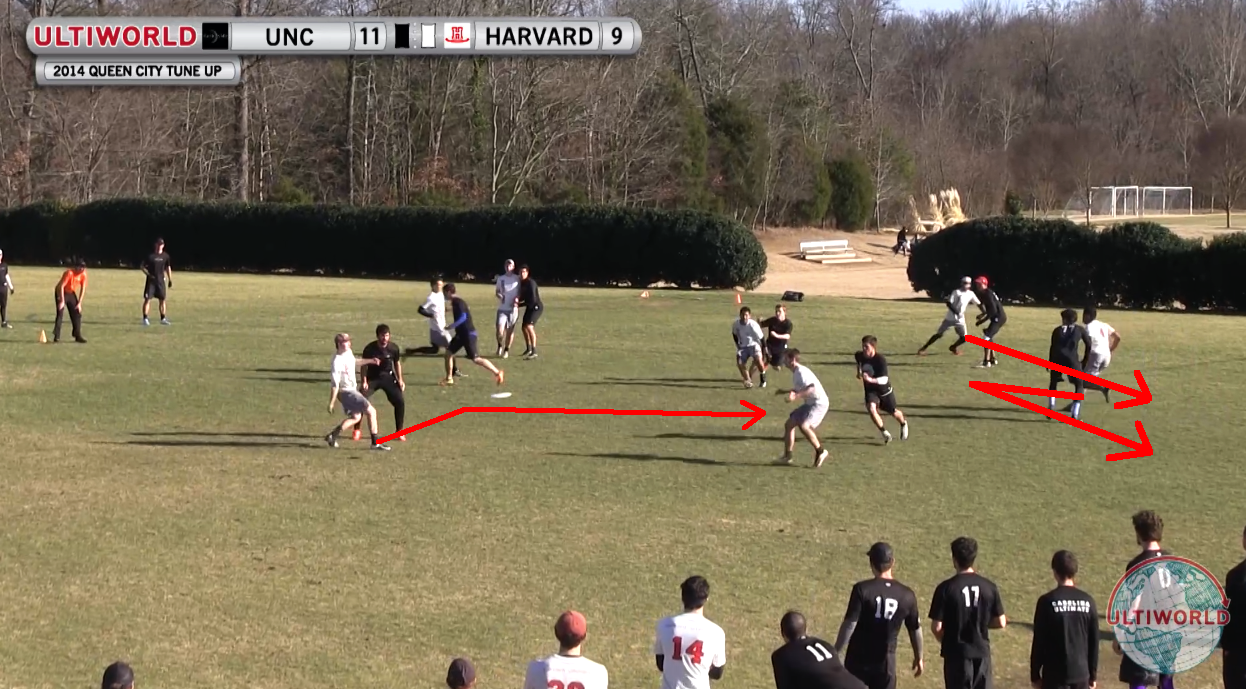

Nixon is about seven yards into his deep cut here and his head is still facing down and forward in an effort to generate as much separation as possible. Notice how a second UNC defender — Christian Johnson — keeps his body square to and eyes on the thrower, looking to help deep rather than focused on denying an under to his man.

Harvard completes the play when the secondary cutter comes follow with a counter under cut.

This deep cut does a good job of illustrating the concepts of counter moves and defensive attention. When a player moves hard (look at Nixon’s head down, full sprint) or a thrower fakes, it pulls the defenses “attention” to a spot. Whether or not a defender actually physically moves in that direction, a defender must really stay focused to not lose attention. This is what happens to Johnson, who doesn’t offer help for the deep cut, but is slow to react to the counter move as he keeps his eye on the thrower, trying to decipher if the deep is about to come.

Of course it sounds easy to just tell players and teams that they need to cut harder if they want to win games. But sometimes you have to make cuts to make space — and avoid, as Chase Sparling-Beckley has noted during commentary “processing first and running second.”6 Counter moves are also especially key in a vertical offense for producing options, and it’s easier to generate them and draw attention when players are at full-throttle.7

The basic idea of a counter move is, as a cutter, if a person runs by you going deep, you need to cut in. If they cut in, you go deep. So if the defense collapses on one cutter there is an option somewhere else on the field. Harvard needs to do a much better job of providing counter moves in order to get the most out of their team.

Of course it’s easy to bring a magnifying glass to any team’s offense and find faults. The good in Harvard’s system is allowing them to play at a higher level than 90% of the teams in the country. Based on the Queen City video, they’d be wise to seek out the last 10% of growth by finding a way to add both additional aggression and organization to their downfield cutting.

See if Harvard can reach the next level this weekend at Easterns, their final regular season tournament. Ultiworld will have live video coverage and reporting all weekend long!

***

more than Pitt’s 45 degree reset structure ↩

Often club-based players, like Jon Nethercutt and Ben Snell ↩

This is a common problem for vert offenses because they[when] don’t initiate deep cuts from the opposite third ↩

pairing an in-cut with a deep-cut ↩

The play eventually ends in a successful dump swing — yet another example of Harvard’s solid reset play ↩

I was watching the 2012 Great Britain v. Japan footage recently and found that Sparling-Beckley made a point about GB’s offense that was similar to my thoughts about Harvard’s offense. He said, during the broadcast: “It really comes down to one major point — something i harp on teams I coach and teams that I’m on. Great Britain, those cutters are watching the ball a lot. They are not clearing hard enough and they are not getting to the spots they need to be quick enough…they are processing first and running second. If GB could just give itself a cleaner palette by getting to their positions (they need to be in) quicker instead of jogging to them while watching the field, that would actually allow the offense to work better, to run through the weird stuff Japan is playing.” Another phrase that captures some of the same concept is “opportunistic cutting.” A person becomes opportunistically open because the disc/mark/field happens to be aligned in their favor as opposed to creating an opening because of their cutting. Swinging vertical stacks generate plenty of opportunity cuts, but if people become to used to getting them then they don’t run hard to clear the correct space for the offense. ↩

It’s possible that part of the effect in some clips is that, by the final against UNC, some of Harvard’s top cutters may have been more fatigued from the long Queen City weekend ↩