Revolver has built an offensive system of isolating downfield cutters and keeping everyone else out of the way. Although it may seem they're cutting against the grain, they have actually just created a new fundamental.

July 23, 2014 by David Hogan and Alec Surmani in Analysis with 55 comments

Revolver is the best team in the world, and they know it.

This isn’t a point of arrogance or swagger, but rather an overarching principle. It’s a fact that empowers them to think and play differently. And it goes beyond simply having some of the best players in the world.

It’s why Revolver runs the offensive system that they do. With the best talent on their team, they know that if they turn ultimate into simple decisions and 1-on-1 matchups, they can beat anyone.

This article is about that system: the new fundamental.

At its core, Revolver’s offense is about creating isolation cuts and giving their cutters time and space with which to work.

What’s amazing is how many facets of their offense deliberately support this goal, even when they obviously contradict conventional wisdom.

Study this clip — we will return to it later:

http://gfycat.com/ClosedGrandBluefintuna

What looks like just another easy goal is actually the combination of multiple Revolver principles: accurate hucks that can come at any point of the stall count and from anyone, clearing into weird space, and resets that are not as prominently involved as you might expect: At any point in the stall count, when most teams have looked to a dump system, Revolver is still looking at an isolation cutter downfield.

Fundamental #1 — Spacing *Perfection*

Revolver has a great sense of spacing and distance. Like most teams, they prefer to set up their isolation cuts 10-15 yards downfield of the disc, as this makes the cutter dangerous both deep and underneath. With the help of playing on a football field we can see how consistently they accomplish this, and what happens when they set up deeper or shallower.

As we can see in these images, the cutter is set up about 12 yards downfield. He has space to cut either deep or in, depending on what the defender is giving him. He also has given himself some horizontal space with which to work, a valuable tool in Revolver’s cuts. Once the cutter has run out of horizontal space, he is no longer a dangerous threat and will usually have to clear.

What is more unique about Revolver’s initial positioning is when their cutters set up their cuts shallower, around six yards downfield of the disc. While this does give the cutter more room deep, it eliminates any immediate in-cut opportunity without an initial deep push. In order for these cuts to work, the cutter has to be sprinting deep immediately as the cut begins, which Revolver likes to do when they’re worried they set up too shallow.

Here, we see Kittredge is set up six yards downfield of the thrower. Recognizing this, he begins to sprint deep. His defender is in a very common position used to defend Revolver cutters: a few yards deep, but facing in so the in-cut can be closed on.

http://gfycat.com/ZealousShamelessEuropeanfiresalamander

This shallower set-up is very advantageous when the goal is to cut deep. Since so many defenders play deep off of Revolver’s cutters, it takes a little more distance to beat this loose defender deep. Gaining a step deep 20 yards downfield as opposed to 30 makes the throw a little easier and minimizes the chance of an underthrown huck.

In contrast, we can look at an example of a shallow cutter NOT sprinting deep immediately when set up shallowly, a violation of the Revolver playbook.

http://gfycat.com/UnsungElegantEskimodog

Here, the defender is playing off of him deep, knowing he would have to cut deep first to set up an effective in-cut. The slip aside, the cutter makes no definitive move deep, and the defender does not have to commit anywhere. He is simply able to shuffle and reposition with ease to negate the cut, all the while especially eliminating any deep cut.

Like most teams, Revolver also has issues when they set up too deep. The resulting huck is underthrown and turned over.

http://gfycat.com/SnarlingCanineIndochinahogdeer

Revolver uses both a standard and shallow set-up to achieve their aims: a shallow set-up is most advantageous for deep cuts, and a standard 15 yard set-up is most advantageous for underneath cuts.

The Isolation Cut Itself

The two most notable qualities of a typical Revolver cut are the intensity and decisiveness with which they change direction. They rarely dance around or throw in more jukes than they need to. When they spot an advantage in any direction, they explode into that space with speed and commitment. If the defender is unable to match that speed and commitment, then the cut is won. If the defender can match it, then that means there is a different space that the defender cannot guard, and the cutter is able to take that space.

The Revolver trademark cut, built from these concepts, is a hard deep cut that quickly turns into an in-cut once the defender has committed deep.

http://gfycat.com/CircularMarriedDuiker

Like most teams, the Buzz Bullets defenders are wary of getting beat deep by Revolver, knowing Revolver is looking for a free deep cut. You can see the difference in intensity and commitment between the cutters and defenders when they change direction inwards. Revolver explodes in, and Buzz Bullets follow with some degree of reservation to avoid a double move beating them deep. It’s at this moment that Revolver wins their cut — they are so sure and so confident of what they’re doing that they do not delay moving into a new space. It’s already a losing battle for the defender, but adding a lack of commitment to guarding the in-cut makes the battle more lopsided in Revolver’s favor.

Why the lack of commitment? If Revolver is able to simply beat their defender deep and have their thrower huck to a favorable 1v1 matchup, they’ll do that immediately.

http://gfycat.com/ZealousShamelessEuropeanfiresalamander

Defenses adapt to this and play deep off of Revolver’s cutters as a response. The shallower cut set-up may have evolved as a way to still successfully cut deep despite these deep cushions.

The mechanics of the cut

Revolver cutters pay a lot of attention to the defender guarding them. Their goal is to make the defender turn his hips and commit somewhere.

The cutter’s awareness of what the defender is trying to do and where they’ve committed is incredible, and allows them to make devastating split-second decisions during their cuts. Revolver forces commitment from the defender with a hard burst either horizontally or vertically, and then attacks the exposed space. If their deep cut is not fully respected, they will simply cut deep.

Here, Kittredge has a few yards of underneath space to work with, and could cut in for a contested five yard pass. The defender is in an ideal position to defend both deep and underneath. He is sitting deep of Kittredge but has his hips turned inwards, allowing him to close on any in-cut while discouraging a deep cut. Kittredge recognizes this, and begins to work to get the defender to commit somewhere.

He first begins to cut horizontally, and the defender moves in to contest what he thinks is an in-cut. At the exact moment the defender closes, Kittredge begins to burst deep. It’s a do-or-die moment for the defender: with his momentum already going in, he has to sell out to defend the deep cut or he has no shot of catching Kittredge, one of the fastest players in the world. Once the defender turns his hips and sprints deep, Kittredge comes right back underneath for the 16 yard completion.

www.gfycat.com/BreakableHoarseBighorn

Next, we’ll see what happens when the defender makes a different decision. Here, Kittredge (on the 31 yard line) begins a horizontal cut with his defender sitting deep.

As soon as the defender starts moving horizontally and in, Beau plants and cuts deep.

The defender does not sell out deep, and Beau is gone. This is all done in an extremely small time frame, and at times it seems like the Revolver cutter is reacting to the defender’s movements instantaneously.

http://gfycat.com/OnlyOffensiveCondor

Time and time again, Revolver makes these quick changes of direction at the very instant the defender is moving in a different direction, forcing a commitment, however small, from the defender while staying uncommitted themselves. That ability — to force commitment from their defender, recognize that commitment, and change direction in a very small window of time — is both practiced and incredible.

In addition to being very athletic and being able to change direction quickly, they also frequently have the advantage of the cutting angle. We’ll revisit the last image to demonstrate this concept.

The yellow lines show each players’ momentum, and the red line shows where their deep cut will take place. Kittredge will change direction at an acute angle, which is easy to do quickly with just one step. The defender must change direction at an obtuse angle. There’s no way he can change direction as explosively as the cutter. Kittredge recognizes this, immediately bursts deep, and it really isn’t a contest after that.

Kittredge is forcing a commitment from a defender while staying uncommitted himself. With predominantly horizontal momentum, any move by the defender either deep or in will give him an advantage in the opposite direction which he can quickly exploit.

Revolver’s ability to notice these angular advantages is not just limited to Kittredge. In the screenshots and clip below, Wiseman is running deep, getting ready to set up his isolation cut. Both Wiseman and his defender are jogging diagonally deep at the same speed, with the defender in his proper positioning on the force side.

The defender must push his momentum more horizontally to avoid his own player, turns his hips a bit, and gives Wiseman a brief advantage. He notices the defender has to change his line slightly more horizontally in order to avoid running into a teammate. As soon as Wiseman notices he has an angular advantage, he sprints deep to score.

Noticing this, Wiseman takes off, ducks his shoulder and takes the inside positioning, winning the footrace towards the end zone. Whether or not it’s a pick is irrelevant to the quickness of Wiseman’s reaction and subsequent acceleration. He sees an advantage and wastes no time acting on it.

http://gfycat.com/OddballResponsibleGelding

This angular advantage is most prominent and easily gained in a cut with horizontal motion, especially with so many defenders playing a few yards deep of Revolver’s cutters.

When the defender does fully commit to taking away the deep cut, the cutter will then have the advantage on the in-cut for two reasons. In addition to being shallower than the defender, the cutter has the advantage of initiating a change of direction rather than reacting to it. Most defenders are wary about giving up deep cuts to Revolver, and will not sell out to immediately close in on the underneath cut in case Revolver then cuts deep.

http://www.gfycat.com/ImmenseFrankAcornwoodpecker

You’ll notice that as Wiseman decides to cut underneath, he is already using his upper body to lean into the direction he wants to run. This gives him a very quick change of direction that a defender really cannot match when they are reacting. There is no indecision on Wiseman’s part. Once he decides to cut in, he changes direction as quickly as he can and bursts for the in-cut. This gives Wiseman three advantages: positioning, initiating, and decisiveness. When Revolver is able to set up these sorts of isolation cuts, they are almost impossible to defend.

How Revolver creates opportunities for isolation cuts

While the isolation cut is featured, the rest of the players on the field must work to give that cutter space. This begins with the handlers, who set up contrary to conventional wisdom.

A classic reset system involves a handler working to get open either upline or back and towards the break for a reset. Both the upline cut and the initial set up clog downfield throwing lanes, however.

In this image, Wiseman wants to throw a downfield break, but a handler has set up even with him, bringing a defender into the area and preventing this yardage-gaining break.

To avoid this situation, Revolver has their handlers set up behind the disc as often as possible. You can see here that Kittredge has his choice of both the break and force lanes to throw to a downfield cutter.

This handler set-up shows their level of commitment to giving cutters time and space. The set-up effectively eliminates upline handler cuts and the resultant power position huck opportunities as a consistent element of their offense, yet they are more than willing to make that trade off. Rather than aiming for give-and-goes and upline cuts, they simply use their resets to keep the play alive and to horizontally change the angle of attack when necessary. This often makes it seem like their handler cuts are not generating anything, and are just settling for negative yards.

http://www.gfycat.com/DazzlingTerribleBetafish

But this is not an accurate assessment. They are generating time for the cutters, and are giving them as much space to cut into as they can. Downfield, Revolver predominantly runs a side stack offense, which is the ideal offense to give one cutter loads of space, and allows them to set up their cuts shallower than normal when they want to.

The downside to a side stack is that it’s easier to set up switches and brackets and defend 2-on-1 rather than 1-on-1. In order to prevent brackets and switches off of the pull, Revolver brings elements of a horizontal stack into their most common pull play. As we see here, Revolver has run this play, often called Diamond, as a basic way to start a horizontal stack offense.

http://gfycat.com/ImpressionableUnknownFalcon

Later on in the 2013 season, Revolver moves this same initial play into their side stack, forming a side stack with two isolation cutters. After the play is run, they naturally have transitioned into their isolation-heavy side stack.

http://gfycat.com/UnderstatedSolidFallowdeer

This gives Revolver the best of both worlds: the honest defense of a horizontal stack combined with the large isolation cuts of a side stack.

Revolver is also very skilled at creating lanes for isolation cuts during the run of play. They do this most often by clearing the force sideline and forming a side stack on the break side. They clear the force side because a vertical isolation cut is very difficult to throw to when the disc is further to the break, and Revolver does not want to run cuts that are only dangerous in one direction.

When a cutter clears off of the sideline, the clearing cutter can either set himself up to be the next isolation cut, or clear. Revolver’s clears take them back towards the middle (or, sometimes as far away as the break) and deep, putting themselves in a perfect position to be the next isolation cutter.

http://gfycat.com/UglyFewAngelfish

The wide cutters are aware of this, stay out of the way, and allow that clearing cutter to immediately insert himself back into the play as the next isolation cutter. In addition to the clearing cutter naturally being in a great position to be the next cutter, this quick transition from clearing to cutting makes it difficult for a defense to poach off of clearing cutters. When vertical space is limited near the end zone, that same clearing cutter will still look to be active and cut next should the strike cut fail.

http://gfycat.com/QuarterlySelfishFlee

Once again, the rest of the cutters stay out of the way and allow that clearing cutter to set himself up. Most of Revolver’s cutters have found themselves behind the disc, and they are in no rush to change that. Revolver currently has a 2v2 matchup downfield, and bringing 3 more cutters into the mix would only clog up space. The clearing cutter forces the defender to run with him, as leaving him uncovered would result in an easy hammer goal because of all of the space he has. Though the defender knows the strike cut is coming, he cannot leave his man to defend it. Once the isolation cut itself has begun, Revolver’s inactive cutters keep themselves out of the way and allow isolation cutters moving deep to come back underneath.

This is illustrated in these two next examples. Shown here, Wiseman is the isolation cutter. As he cuts deep, Schlachet’s defender poaches off to help cover Wiseman deep. Schlachet realizes this, but directs Wiseman to take the underneath cut rather than freely take it himself.

http://gfycat.com/LastKnobbyBlesbok

Revolver wants their cutters to be able to turn failed deep cuts into large-in cuts, and the inactive cutters hold back to allow this to happen. A more drastic example of this concept is shown here. Kittredge cuts deep and picks up three extra defenders, though none of uncovered cutters look to cut back in, allowing Beau that space if he wants it.

http://gfycat.com/GraciousPrestigiousCornsnake

Once again, this seems to go against conventional wisdom. But Revolver has chosen their offensive priorities, and they build a fence around them. When in doubt, they give the active isolation cutter their space. They may not get some free underneath cuts, but they’d much rather make sure the isolation cuts are allowed to fully develop than risk clogging that isolation space.

Revolver will even go so far as to have their inactive cutters clog handler space as the disc moves down the field by lagging and jogging behind. A bit counterintuitively, the best team in the world may be the first team to have mastered holding off on cuts.

Typically one of the first things taught to new players when learning an offense is to have the stack (whatever kind it may be) constantly be moving downfield ahead of the disc. Revolver will often take an opposite approach, keeping three handlers or even more behind the disc. Since handler motion is not the driving force behind their offense, less space for their handlers is not a big detriment, and as a result the 2v2 matchups are given a lot of space to work with. This is especially effective near the end zone.

Many end zone offenses run a vertical stack with only two active cutters. Keeping the other cutters even with or behind the disc and to the break side prevents inactive cutters who would otherwise be in the middle of a vertical stack from taking up space or allowing their defenders to poach. While this eliminates quick motion to the break side, Revolver has some of the best 15-30 yard away flicks in the game, and can score just as effectively with in-out cuts as most teams can with breakside motion.

In both images, the isolation cutter is making his cut and the next isolation cutter is beginning to jog downfield and set up his cut, usually a strike cut if the active isolation cutter clears. The rest of the cutters are either even with or behind the disc. As we are about to see, this cutter lagging also opens up cuts that are not available in a standard vertical stack near the end zone.

Here, Wiseman is on the break side and will want to make a strike cut to the back cone. Jeffery is in a space that he’ll have to clear, and will clear to the break side while also being a potential target for a hammer. Both of their cuts would take them through where a vertical stack would normally be (shaded rectangle). Because every other cutter has stayed behind the disc, this play runs unhindered and is successful despite several poaches.

Here, Wiseman is on the break side and will want to make a strike cut to the back cone. Jeffery is in a space that he’ll have to clear, and will clear to the break side while also being a potential target for a hammer. Both of their cuts would take them through where a vertical stack would normally be (shaded rectangle). Because every other cutter has stayed behind the disc, this play runs unhindered and is successful despite several poaches.

http://www.gfycat.com/MildThoseFattaileddunnart

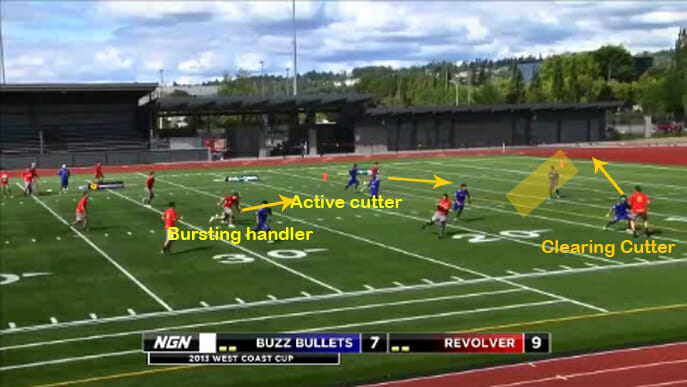

I labeled the bursting handler because of how his actions show that this concept is not an accident or laziness. He attempts to assert himself downfield and has beaten his player upline. He quickly recognizes the 2v2 isolation set-up they have downfield, and immediately stops his cut to allow the play to develop. The final way Revolver creates opportunities for their isolation cuts is by holding the disc and looking downfield longer than most other teams. The thrower gives the cutter ample time to get open and does not look at other options until high in the stall count. This gives Revolver’s offense a very deliberate feel to it.

http://gfycat.com/AcademicFarflungAtlasmoth

Unlike a lot of teams, they don’t value throwing hucks or breaks from motion and a stall count below three. Because of their elite throwing ability, they choose to sacrifice the small advantage that they would gain from that for giving the cutter more time to finish his cut. This also allows a cutter to cut deep at any time during his cut, rather than having to time it earlier if he wants to cut deep.

Knowing the cut doesn’t have to be timed perfectly to be effective, the inactive cutters will usually hang back a half of a second longer than usual in order to ensure the active isolation cut succeeds. They’re in no rush to get their cut started if it might clog the isolation cut. Rather than aiming to throw hucks from an upline power position, Revolver is more concerned with what they’re throwing to than where they’re throwing from. They want a one-on-one matchup downfield that has a step deep early on the defender and is sprinting 100%. If they gain that, they will almost always throw their huck.

How Revolver connects isolation cuts

We’ve touched on their isolation cuts, but how does the offense progress down the field? How are isolation cuts connected? As they run through their isolation cuts, there will typically be one other cutter setting up the following iso as the rest of the cutters stay out of the way. I especially like this clip, because the isolation cutter after Higgins is not simply the second deepest member of the stack. Schlachet takes that cut, having begun the point set up as a third handler. He spends the first two cuts sprinting downfield.

http://www.gfycat.com/DeliriousDarlingAfricangroundhornbill

The rest of the play is predictable but effective — there is an isolation cutter and a secondary isolation cutter setting up his cut.

Now we come back to the first play, the one that touches on most of the elements discussed here and gives a really good glimpse of how Revolver’s offense puts it all together and flows:

http://gfycat.com/ClosedGrandBluefintuna

Revolver wants to move the disc down the field with this set up: handlers behind the disc, one isolation cutter, one secondary cutter setting up his cut, and lagging cutters even with or behind the disc. As the play develops, we see how these concepts develop and work with one another.

The handlers and other cutters are lagging behind, giving the iso cutters plenty of space. It is very clear who the primary and secondary targets are, and a lagging cutter methodically moves from the side stack out to become the secondary cutter as passes are completed.

How Revolver responds to the poach is fantastic. It is not the poached cutter’s turn to be the secondary isolation cutter when he begins cutting, but you can plainly see between him and Wiseman (who is next in line) as they understand that there is a poach that needs to be exploited. The double cutter wants to be doubled. He drives downfield and into space knowing he will probably not get the disc, but will end up bracketed by two defenders in an unideal, too-narrow space for the defense.

Wiseman, the poach cutter, does not impose himself upon the play, rush his deep cut, or clog the other cutters. When he has his chance within the structure and the flow of the offense he takes it, finding the open space but attacking it decisively. Kittredge isn’t known for his hucks, but everyone is empowered to throw to isolations in the Revolver system.

The last thing to emphasize about Revolver’s isolation scheme is how they break from tradition. I have spent several years repeatedly teaching various youth teams to have the stack move downfield quickly and have our resets set up in a way that gets the disc from the force to the break side quickly. These are supposedly fundamentals!

But Revolver has set up a new fundamental: isolation cuts that are given time and space. And from that concept, everything else naturally falls into place. So while Revolver does have incredible athletes and elite throwers up and down their roster, it is this isolation system they’ve developed and their willingness to go against the grain that has propelled them to multiple National and World Championships and has us excited to watch them this year.