Continuing our club video breakdown series, powered by Agility from Five Ultimate, we look at the no dump verticial stack. Standard vertical stacks often employ two handlers and five cutters downfield. But some teams run six person stacks with completely empty backfields, a formation decision that has implications for both the resets and overall offensive flow.

August 12, 2014 by Benyamin Elias and Ian Toner in Analysis with 20 comments

In any offense, teams must make strategic decisions about the utility of their resets. The most effective resets look to both give the offense a new stall count and, ideally, move the disc to an advantageous region of the field.

The “no dump” vertical stack is an offensive system used most notably by Boston Ironside1, but recent college champion Colorado Mamabird also experimented with it this past season.

The system features a single player holding the disc with the six other players composing the stack. This formation allows for aggressive resets that lose fewer (or even gain) yards, while still sometimes moving the disc to an advantageous (breakside) position.

The Six Person Stack

Ironside and Colorado frequently set up in a six-person vertical stack. By eliminating traditional resets, or at least reducing their presence from their offense, Ironside and Colorado open up more downfield throwing lanes for their cutters. Without a dump and defender in the backfield, the thrower often has completely open space to throw to if he can break the mark.

The setup requires confident throwers that are able to break the mark; it’s fitting that Ironside and Mamabird, two of the most skilled teams in their respective divisions, employ the system.

One downside is that the upfield resets in the stack provide fewer obvious opportunities to attack from the handler set. It’s more difficult to run dump sets with traditional handler weave motions (upline and backfield handler cuts, at 45 degree angles) or to utilize give-go handler systems that look to gain yardage when downfield cutters stagnate. But, on balance, the six person stack resets also lose fewer yards, allowing the offense to maintain hard-earned yards gained from repeated under cuts.

A nice, if unusual, camera angle again shows no backfield reset as Ironside cutters return to the stack (the last cutter is off screen clearing into the stack from the flick side).

Ironside’s defensive line also sets up this six-person vert.

Although Colorado tends to have their throwers linger backfield longer than Ironside, they also put six players upfield while moving through their offense.

Moving Through the Offense

This “no dump” vertical stack functions differently depending on whether the disc is in motion or if the offense is starting off a stopped/dead disc.

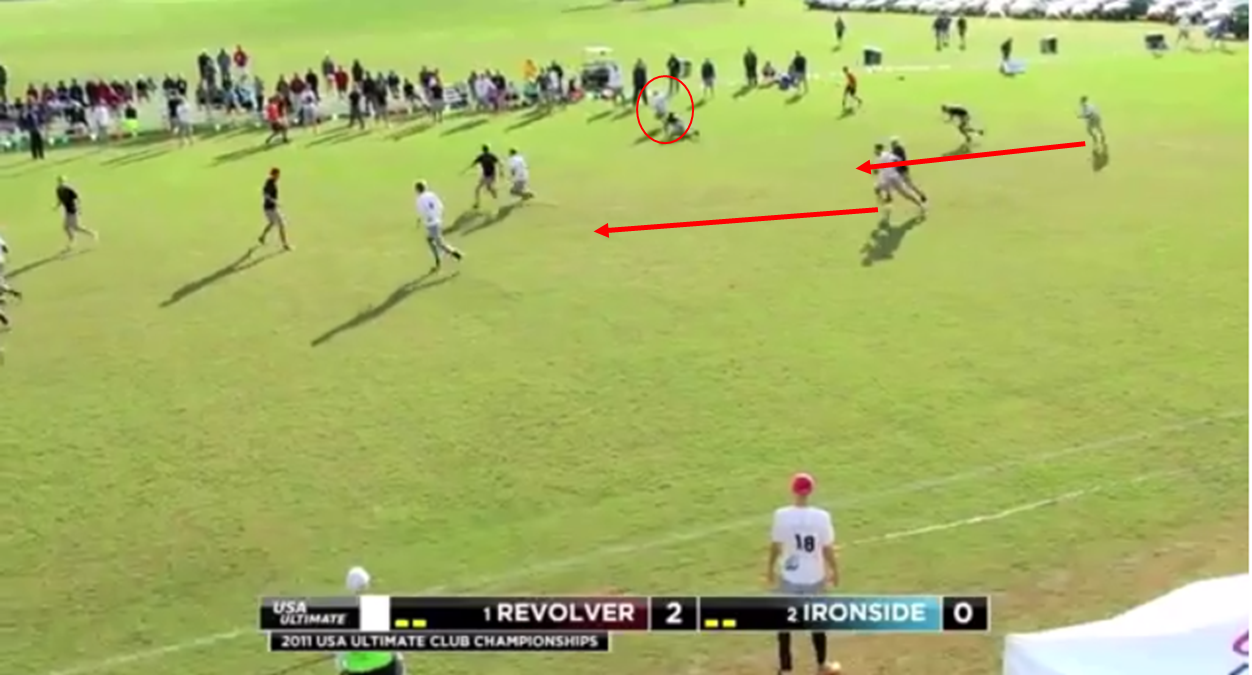

When the disc is moving quickly, throwers are very quickly cycling through the stack. Notice the transition from the break side reset as both handlers move upfield into the stack.

transition from the break side reset as both handlers move upfield

In the clip below, recognize how the throwers repeatedly get rid of the disc and immediately clear upfield into the stack.

For many teams, especially less-skilled teams, the desire is mostly to keep handlers in the backfield and cutters upfield. Handlers are often forced to make a decision after throwing: Do I clear upfield, into the stack, and potentially make more breakside space for the new thrower? Or do I hang out and stay back, because the team would prefer to have the disc in a main handler’s hands? The no dump vertical stack leans far towards the clear upfield principle, and even throw-first players are encouraged to decisively move upfield, away from the backfield space. Essentially, every cutter is trusted to have the disc in their hands for an extended period and a full progression; no one is a throwing liability who is expected to immediately dump it backfield after catching an under cut.

Ironside does not seem particularly concerned about who the disc is reset to as long as it is still moving. In the clip below, Danny Clark (who is known one of Ironside’s most dangerous deep cutters) comes for the reset in the I/O lane.

Clark comes for the reset in the I/O lane

For Ironside, moving the disc is more important than keeping it in the hands of throwers like Rebholz and Markette.

But what happens when the disc does stop moving? This often happens just past the midfield mark, once initial momentum has halted.

The “No Dump” vertical stack is a bit of a misnomer; it’s not that there are no resets, it’s just that the dumps are positioned upfield.

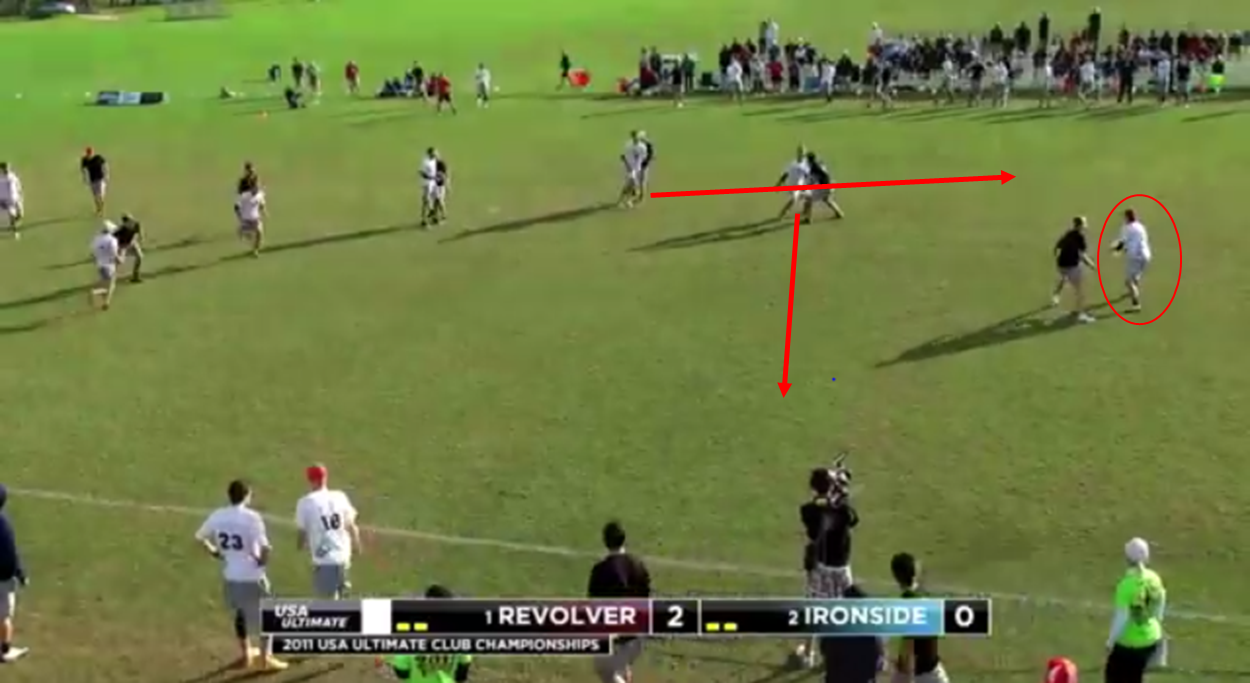

In the clip below, Stubbs has the disc towards the break side with the stack almost completely reset. The front of the stack goes break side for either the I/O or the around break at the same time as the second in the stack comes to get the force side swing.

Ironside’s defensive lines like to use the same progression, with the front cutter going break while the second cutter goes to the forceside. While this is the more popular variant of the reset system, it may be more accurate to say that the front cutter makes the first move, based on where he sees the best opening. The cutter behind him is likely to move in the opposite the direction, so that the thrower has at least one option to each side — with both cuts and progressions happen at almost the same time.

Ironside’s defensive lines use the same progression, as seen in the clips below:

When the disc is on the force side, the front of the stack often makes a move into the force side (unfortunately a double cut in this example) and the second in the stack comes around for the swing.

the second in the stack comes around for the swing.

Ironside sticks to these resets right up to the endzone line, even using them to generate scores. With the disc trapped on a sideline, the Ironside player makes good pivots to move the mark and really open up easier throwing lanes on the force side, where he eventually throws. You can also see how the second reset is a bit more patient in the endzone offense, as he tries to set up his upline cut while the first dump is moving, rather than moving at the exact same time; this helped synchronize the timing better in the trapped situation, given the longer pivot and fake from the thrower.

even using them to generate scores.

Colorado, on the other hand, often switches to the more traditional strike-fill reset close to the endzone.

traditional strike-fill reset close to the endzone.

Off the Pull: Before Getting into the No Dump Stack

Ironside rarely sets up its six-person stack immediately. Rather, Boston either runs a pull play or sets up a different stack before moving through its offense. Although pull plays are beyond the scope of this article, there’s ample evidence from the 2013 U.S. Open final. Ironside’s cutters flood across the field to the break side, creating space for an easy force side under.

creating space for an easy force side under.

The alternate stack that Ironside sets up — a more standard vertical stack formation — is designed to take advantage of deep space. Ironside sets up a deep vertical stack with the reset on the break side; the cutters are intentionally set up a bit deeper than average but also do a good job of leaving space near the thrower clear for resets.

Implications for the Offense

As alluded to earlier, there are a few immediate implications of the no dump vertical stack beyond the setup itself. For one, teams tend to give up a bit of the power position that both traditional resets and aggressive handler give-go movements can generate. Second, teams tend to isolate slightly larger and longer throwing windows. This is especially true and advantageous when a strong or tall thrower, with good around breaks, gets the disc and is essentially given freedom to look upfield for the entire ten second count. Finally — in part because there is less handler power position generated and in part because every cutter is trusted to be isolated with the disc — offenses that run the no dump vertical stack may look more cutter-oriented. They may have more cutter to cutter hucks than other vertical stack offenses, where the hucks would come from the two handlers or front of the stack.

The way that Ironside positions and runs their resets speaks to how they want to run their offense. Most traditional reset systems set up a handler 45 degrees behind the thrower when the disc is on the force side and roughly even with the thrower when the disc is on the break side. The front of the stack functions as the second reset option. Although there are variations on how teams use these positions to facilitate their offense, the positions generally give handlers strong opportunities to attack upfield (gaining power position) and towards the break side.

Setting up on the 45, handlers can make either a push upfield for power position or a cut behind the thrower for an attack at the break side with a trailing mark. This positioning also facilitates give-go moves, a particularly active method of attacking from the handler set. Rhino is one team known for running lots of handler give-go movement, as can be seen in the clip below.

This positioning also facilitates give-go moves.

In contrast to the above clip, Ironside’s previously discussed initial stack utilizes a different (though not uncommon) reset set-up, positioning the off handler on the break side. The combination of a break side reset and space in front of the stack serves to open up downfield throwing windows even though a dump is set in the backfield. The positioning also allows under cutters space to huck; although the initial set-up is too deep for a standstill huck, it is the perfect depth for a continuation huck. This is one of Ironside’s favorite offensive moves (think a Stubs undercut to a streaking Kapinos or Clark), and it is after threatening this attack from their traditional stack that Ironside often transitions into their no dump set.

Colorado used these resets to gain yards while they patiently waited, deep into a stall count, for their terrifyingly deep cutter set to gain separation. This separation would frequently materialize in the form of a deep shot.

materialize in the form of a deep shot.

You can see from the clip above that Colorado’s use of the no dump vertical stack is less rigid and frequent than Ironside’s. For Mamabird, emptying the backfield and giving more space to the thrower was an option, rather than a formation — often employed when a powerful and capable thrower like Jimmy Mickle got the disc. In those situation, the dump was more eager to clear upfield, knowing the thrower would eventually find sme cutter in open space and deliver the disc, preferably deep.

But when such shots weren’t available, Colorado was also willing to march the disc up the field, waiting until cutters got open under.

The clips showing Ironside’s offensive flow clearly demonstrate the emphasis on cutters; as previously stated, handlers immediately clear into the stack as the throwers continue to hit cutters on the force side. This style doesn’t utilize the give-go handler movement that Colorado used to advance up the field. Ideally, Ironside looks to get the disc to a cutter (often Stubbs) under, who then turns to deliver a flick huck for the score.

deliver a flick huck for the score.

Implications for the Defense

This offense relies on cutters to consistently gain separation and generate yards, but it also places a high demand on handlers to execute crafty break throws to move the disc and maintain those yards. Defenses can limit the offense either by disrupting upfield cutters or contesting upfield break throws.

The best challenge to a six-person vertical stack: altering marking strategies. Asking marks and front-of-stack defenders to stay tight on the breakside, potentially even shading toward the inside lane, tightens that reset lane.

In the semifinals of the 2012 College Championships, Pittsburgh used this adjustment to limit Carleton’s dangerous handler set. Although Pitt began the game marking traditionally, they eventually recognized that the majority of Carleton’s offense was predicated on I/O break throws from the handlers. The defense adjusted towards the end of the first half.

The defense adjusted towards the end of the first half.

In addition to moving the mark further toward the inside lane, Pitt positioned the break side handler defender to take away around throws. The front of the stack defender also moved closer to the IO reset lane. Although this positioning allows a relatively easy reset to the break side handler, it makes upfield break throws much more difficult.

Of course, it would be difficult to fully employ this strategy against Ironside because there often isn’t a backfield handler to poach off of. That is the intention of the no dump vertical stack and one of the reasons it works so well! But tight coverage at the front of the stack is essential to slowing down their dumps; by staying on the hip, you can force the reset to be an extremely tight (and potentially dicey) break throw.

It’s also possible for the second dump defender to anticipate his man’s movement by watching the first dump; Ironside usually moves the second dump in the opposite direction of the first. Furthermore, mixing up marking strategies by incorporating straight up forces or forcing into the stack should also be tried in an attempt to slow down upfield progression.

The danger of any formulaic defensive strategy against a team like Ironside or Colorado is that many of their players are smart enough to adjust. Let’s say you notice that a lot of Ironside’s resets are IO breaks, and you begin to stay tighter at the front of the stack. Intelligent players will take advantage and make their reset cut to the force side.

Takeaways

- Ironside and Colorado set up their vertical stacks with six cutters upfield. This positioning enables them to execute resets that don’t lose, and sometimes gain, yards.

- Strong cutting, even for the “resets”, is required to gain yards in the absence of attacking handler movement. However, handlers are put under a great deal of pressure to execute break throws for resets that do not lose yards. Often times, though, there’s so much open space that these break throws are less difficult than they first appear.

- Defending these systems requires a strategy that challenges the connection between the isolated handler and front-of-stack resets: marks and defenders that contest I/O lanes are effective.

The 2014 Lecco video footage showed less of this formation from Ironside than we’ve seen in the past, something to keep an eye on moving forward. ↩