Sion "Brummie" Scone goes into more detail about the Team Great Britain tryout process.

December 23, 2014 by Sion "Brummie" Scone in Analysis with 3 comments

In part one of this series, I talked about the athletic assessment procedures we used during the tryout process for Team Great Britain. Part two takes a look at actual implementation.

Field-Based Skills Assessment

So, how to make sure the players who try out are tested fairly?

Firstly, new drills were designed, rather than using existing ones, because use of any drills used as standard by some – but not all – of the players would give those players an unfair advantage. New drills provide a level playing field. In addition, new drills help to assess who can understand quickly, who can pay attention, and who can adapt to a new situation; i.e. “coachability.”

Why drills, and not just scrimmages? I wanted to force players to show me their skills, not simply show off their strengths and hide their weaknesses. By forcing them into game-like scenarios, nonetheless in a confined drill setting, we could see how comfortable they would be in a variety of situations. Just watching people play ultimate isn’t going to give you a good idea of their abilities; one player might make great cuts but never get the disc due to poor cutting from team mates, for instance.

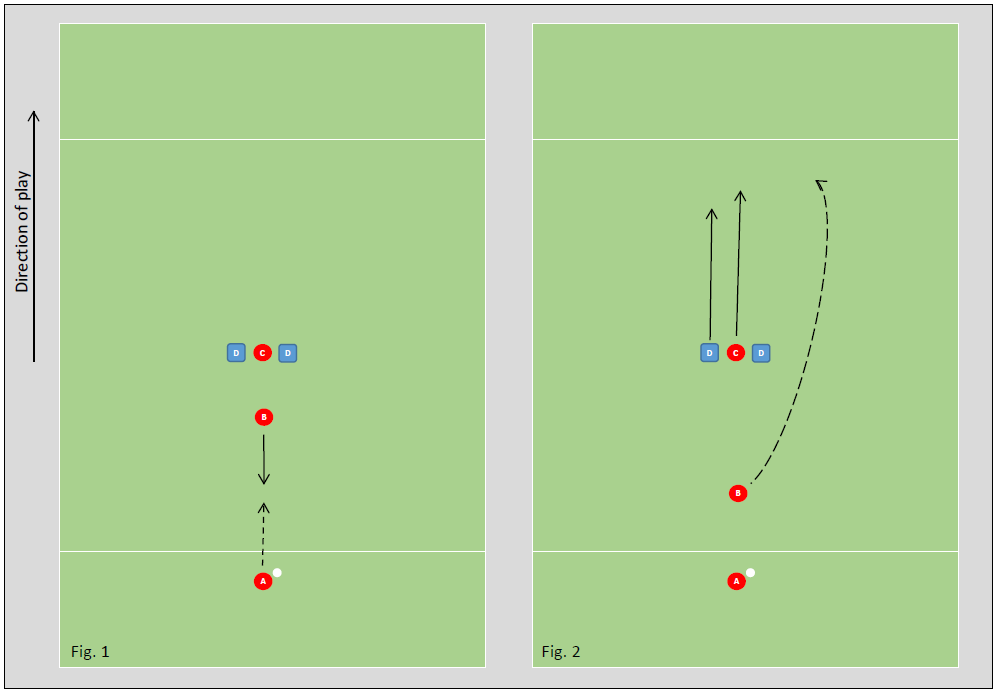

Here is an example of a drill designed to test each player’s ability to assess the field; in Fig. 1, player B has their back to the field where two defenders cover the receiver C. B cuts directly towards A, who throws a gut pass. Meanwhile, the two defenders have decided between them which one will play defence on the long cut that C is about to make; the other defender doesn’t take part in the drill once the disc is checked in. B must then turn, assess where the defender is, and throw long to C by choosing a throw that avoids the defence; in Fig. 2 you can see the defender covering from the left side, so the throw goes to the right shoulder of the receiver.

To reduce bias from coaches, I assigned each coach to grade one component of each drill; one graded players throwing, one graded the cutter, one graded the defender. By using the same player to grade each player on a single attribute, I was relatively confident that all players would be graded in the same way. It also prevented any one coach from providing data on any area that wasn’t assigned to them, limiting potential bias when grading club team mates.

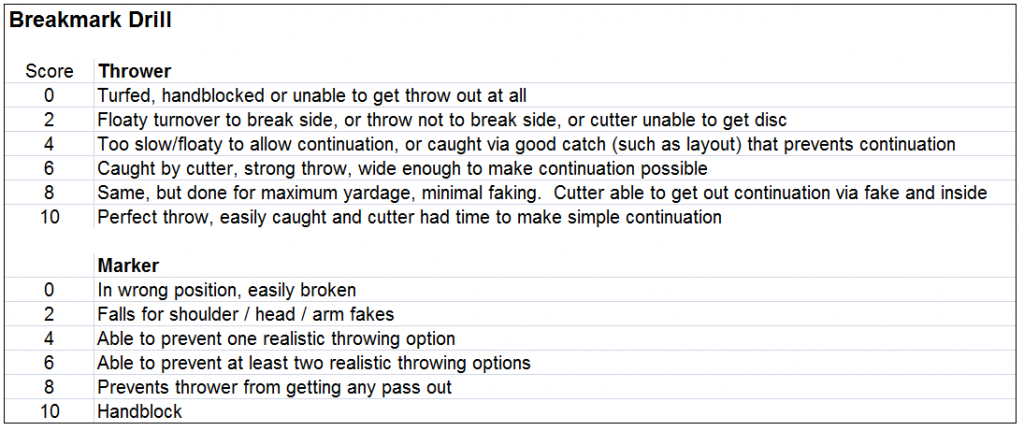

Here’s an example of a grading sheet handed to the captains:

We also set the scene; every player was to imagine they were at the European Championships, representing their country in a big game. Easier said than done, yet each player knew that their chance to play for GB was on the line; tryouts are the closest thing to a big tournament in that respect. We’d need to use other tricks to keep intensity high during the middle of a long season, but at tryouts, people brought energy and passion. We wanted them to bring maximum intensity on the field.

Then we set them at each other. It made for an entertaining and enlightening day. By running several rotations of each drill, then getting mean scores for each category, we were able to build up a picture of the kind of player they were. Some of the results were surprising – that “handler” turned over more than you’d initially suspected, or that “defender” scoring below average on defence, for instance. Any obvious trends led directly to feedback to the players on the areas that we’d like them to work on in the off-season.

In the end, I simply took the mean of all scores and ranked the players top to bottom. The selectors had also been making individual notes on all players; these were collated and discussions had. Similar comments from multiple selectors, now backed up by data, could be used to draw conclusions on the strengths of individuals. I felt a lot more confident cutting someone because I could show that they consistently scored low in comparison to others. I felt that the entire process was successful when the top ranked player was Christian “Wigsy” Nistri, one of the most dominant players in the country at the time; the second ranked was a relative unknown at the time who went on to captain the GB World Games team in Cali three years later: Rich Gale.

In short, most of the top performers were people we’d expected, but this process also drew our attention to some people who hadn’t previously been on our radar. It’s much harder to spot the players who quietly get on with doing the little things right than it is to spot the players who make big plays, so this process was already getting results.

The committee making decisions was comprised of Marc Guilbert (the GB manager), myself as coach, and a small group of captains, all of whom had represented GB Open in 2008. Rich Gale proved to be an excellent student with a likeable personality and a never-ending interest in self-improvement, and he became a fantastic all-rounder for the O line. Gale was just one example of a little known player with bags of potential and an incredible work ethic; we also took Alex Brooks, one of the U19 squad, purely because Marc and I felt it was important that GB gave some experience to younger players who wouldn’t necessarily actually play in this rotation. Brooks turned out to be one of our most improved players — in many ways he was a role model of the ideal teammate — and he easily cemented his place on the team, something that none of the captains expected.

Some subjective opinions were used; one player was cut because it was felt that they were not competitive enough, despite scoring in the top half. Another well-known player — Justin Foord — performed so poorly that we just gave him the benefit of the doubt; he turned out to be one of the best players on our 2011 roster and a leading scorer for us in 2012. Fortunately, all the selectors knew Justin’s abilities and we wrote off his performance as a bad day at the office.

Of course, this is a subjective view; if we’re willing to look the other way when a strong player plays badly, then how can we be sure we weren’t seeing others having a good day too? This is largely irrelevant in Justin’s case because he was still comfortably inside the cut-off point, and it gave me a list of things that he would need to work on as a player. It’s also no less subjective than just watching people play and making a judgement, so taking data and using it to drive a decision in combination with the subjective opinions of a selection group is still better than not taking the data. The grading sheet still needs to be interpreted, of course.

Analysis Of Our Process

I also wanted to use the data to guide my initial coaching plan. How to deal with all of the different data points? Quite crudely, I took mean scores for all “throwing” based sections, and likewise for “defence”, “downfield offence”, etc, and normalised the results to compare categories on a 1-5 scale.

It was clear to us immediately that throwing was below the standard required to compete at the top, and Colin’s assessment showed us we were below par athletically. Given how long it takes to improve throwing & fitness, these became our top priority. Other aspects — team structures, cutting patterns, handler resets — were slowly addressed over the course of the 18 month programme; we left zones until the end of year one, for instance. Not because we wanted to, just because there was so much to cover as a team. All of our players were lacking in some critical aspects, and we needed to cover even the fundamentals repeatedly.

It paid dividends though, as the team dominated most opposition at the European Championships at the end of year one (and we’d have taken gold if not for those pesky Swedes). Certainly our man to man defence was capable of crushing most opposition, and few teams could match us athletically at WUGC — and none could at EUC. As one of our captains, Dave Pichler, pointed out to the squad: “being athletic doesn’t win you games, it gives you a platform to win games. It’s the entry ticket to the competition” (or words to those effect). The focus on throwing paid dividends too. Feel free to watch back the NGN or Ulti.tv footage from Japan and you’ll hear a number of time when the commentators remark that our throws look ugly but go exactly where they need to be for the receiver to reel them in.

Did we get the right people? Well, one thing is for certain, and that is the drop out rate was very high. Whether we failed to screen for commitment level, whether people just didn’t enjoy our training sessions, or they didn’t believe that the team could achieve anything, a lot of people dropped out. From an initial squad of 40+, we made two cuts, brought in two new players, and took 26 to Japan. The others all dropped out; that’s about a third who quit. Some due to injury, some due to becoming first time parents, or other “real world” problems. Two said that they didn’t enjoy the team and didn’t want to be part of it, and a few said they didn’t think the team could achieve anything and quit. It’s a high attrition rate, but given the demands we were making, it was unsurprising.

What did we miss? Well, as the WUGC final indicates, mental strength. Why does an entire team suddenly start dropping simple catches or turfing open side throws? We’d played through worse wind against Japan and Australia and scored plenty. Revolver definitely punished our mistakes, but they were our mistakes. Credit to them for putting our resets under pressure, but we can’t credit them with making us turn over on uncontested passes. We were a young team that fed on confidence. We aimed to start on offence every time, and actually only scored once without turning over in all our games at WUGC.

Most games we went behind and came back through the strength of our D line. Whether we should have deliberately taken some older players with more experience purely to get games started better is something that I’ve considered many times (in reality, we didn’t actually have any candidates matching these criteria who applied). Certainly if we’d traded to 3-3 with USA then we might have grown in confidence (we’d led them previously 10-11 – but gone on to lose 15-12 – at Labour Day 2011).

Clearly, we didn’t come up with a perfect way of assessing everything that makes a great ultimate player on our first attempt. Some of the players that we knew from experience were big play makers fared poorly on our tests. The question is simply: why? Were they just having an off-day? Was our bias showing true? (i.e. they were not actually as good as we had previously thought). Were some people consistently getting tougher matchups than others? More likely that there are a number of aspects that our rigid, formal drills could not assess; we were very aware that ultimate is a game that requires emotion to play well. Drills can replicate some aspects of a game, but not all.

By forcing the scenario, we were unwittingly putting a negative bias on players who can make good decisions about which scenarios they manufacture and which they don’t; for instance, some people never break marks in games because they always dump, while others always try to break the mark and sometimes turn over. The very fact that one of our top players, Justin, scored so badly indicates that the methods are flawed…even if its just because Justin is easily bored by drills. The cost-benefit analysis is impossible to measure at the level of an individual – even if the team objective is to break marks – because having a player who realises their own weaknesses is an asset in itself.

Would I do it again? Given the time, definitely. The physical assessment is a no-brainer, but only if you are going to use it to show player weaknesses, track improvement, or use the scores for selection. If not, then it’s a waste of time and money; timing gates aren’t that cheap to hire! The skills assessment was good, but we were judging entirely off a single day’s play. For a future GB cycle, I’d recommend multiple tryout dates with a progression of scored assessments that can go much deeper than we were able to. Even our most experienced captains made some very different judgments than the scores indicated — bias is everywhere — so if you truly want a fair tryout, then scoring is a must. Otherwise, you’re going to miss something.

As it was, we were able to use the “objective”, data-driven results to kick start our development programme. Because we’d taken the time and effort to assess each of our squad’s abilities, provide them with facts and figures to support their individual training goals, and send them away with a clear message of what we expected to see from them, everyone got a fair start. I also insisted that every player post on our fitness blog every week, and provide me with a printed workout sheet every practice; this forced them to record every workout, which soon showed up those who did or didn’t train often enough, or at sufficient intensity! I doubt that we’d have seen the improvements that we did over the course of one year without this approach, and I have no doubt at all that it was key to having such a solid start to our programme.