What's next for the kid from the South End?

September 25, 2015 by Katie Raynolds in Profile with 19 comments

Khalif El-Salaam has it all planned out. He intends to be the best player in the world by the time he’s 27.

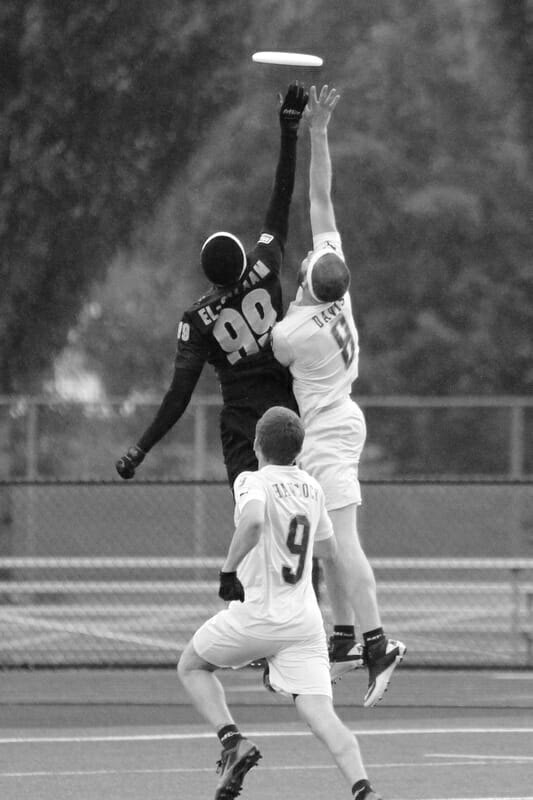

For most people, that kind of plan is ridiculous. For Khalif, only 21, it’s possible. Khalif is one of the most entertaining and talented young players to emerge in the sport over the past few years. He caters to the highlight reels with elite athleticism and jaw-dropping grabs. In addition to being named the MLU 2014 Breakout Player of the Year, Khalif made a small piece of league history this year by signing a 3-year contract with the Seattle Rainmakers, the first multi-year contract for the division.

Khalif has played on some of the world’s biggest stages, and because he’s Khalif, he always puts on a show. At the 2012 World Junior Ultimate Championships in Dublin, Ireland, his team was handily beating Australia during a pool play game, but it was clear Khalif was playing with reserve. When asked why he wasn’t doing more on the field, Khalif shook his head and said cheekily, “I only make plays for two reasons: for the cameras, and for the ladies… and I don’t see either of them here.”

Welcome to Khalif. He’s brimming with energy. Sometimes it comes out in the form of jokes, celebrations, and cheers; sometimes it manifests itself as fiery call disputes. Always it translates into an earnest intensity he thrusts onto the field. Team USA would go on to win that game and eventually the world championship in Dublin. It would not be Khalif’s first or last victory.

Khalif can tick off his list of medals in quick succession: one Westerns title, “a couple state championships,” one U19 gold medal, and two U23 gold medals. He also helped Seattle Mixed (now Mixtape) reach its first National Championship finals last year and he competed with the Seattle Rainmakers in the MLU Championships in early August.

He’s won a championship at almost every level he’s eligible for. He’s made Sportscenter Top 10. He dances. He sits on shoulders. And he’s got big dreams.

The Plan

Khalif details the next twenty years of his life like he’s mapping out a practice. In under a minute he walks me through his dreams to become one of the biggest players in our sport.

The age 27 isn’t arbitrary. Khalif heard that something connects in your brain when you turn 25, so a couple years later he would likely be what he calls his “optimal Khalif.”

“You start going downhill at 35,” he said. “If I am the best player in the world at 27, then I get three years of peaking, and then five years to do whatever I want. Do I want to play Masters? Keep playing Worlds? Sockeye? And then I can just downhill coast until my 40s.”

He wants to win at least one Club Championship, and he’d like to represent the USA a total of five times in his life. With three already under his belt, he’s set a good pace.

“Week by week, we train harder and harder”

At Asa Mercer, a middle school on the South End of Seattle, Khalif wasn’t plotting his ascent to the upper echelons of our sport. He was trying to get his football off the school’s roof. Sam Terry, a teacher at Mercer, handed Khalif and his friends a disc. After some persistence from Terry and his fellow coach Rex Gaoaen, Khalif went to his first practice. He wore jeans to protect his knees from the school’s stony field, a choice he still can’t live down. And he fell in love.

The success of the Asa Mercer Mustangs ultimate program has been well documented, and rightfully so. In just their second year of existence, the Mustangs won Spring Reign, the biggest youth tournament in the world. Their team didn’t look or play like anyone else, but they were good.

If you ask Khalif why, his answer will always be hard work. To him, it’s why Mercer is so good. It’s why the Fryz are so good. It’s the difference between North End and South End kids.

“Frisbee is one of the few sports that everyone has the chance at,” Khalif insists. “If you have the right coaching early and you work hard… everyone can be good at Frisbee.”

Sometimes Khalif still goes to middle school practices in his old neighborhood. Ultimate has become a popular sport in at least three of the area’s public high schools, despite little support from the district. These teams don’t have the resources many Seattle private schools allocate to ultimate programs, yet they’re still close on the heels of these bigger, longer-tenured programs. Khalif coaches kids across the city, but he talks about the South End kids differently.

“Even though these kids have all these disadvantages, their competitiveness and willingness to work is what pushes them,” he insists. “I would just tell [these kids], ‘You’re going to beat them if you just work harder than them.”

Randy Lim, founder of the local youth club team Seattle Fryz, cites Khalif’s work ethic as one of his defining traits. Randy remembers a cheer Khalif used to use with the Fryz, one Randy says they have since heard him repeat nationally and internationally:

“Day by day

We get better and better

‘Til we can’t be beat

won’t be beat

Week by week

We train harder and harder

‘Til we are stopped

We won’t stop…”

According to Lim, Khalif believes in these words so much that he refuses to invoke them unless he truly believes the team has worked hard enough. Because when everything else is unequal, effort matters more. When there are so many uncontrollables, commitment and drive become the best tools you have.

The Fryz Family

Khalif could have become a good ultimate player through sheer determination. Instead he’s become a great ultimate player, winning gold medals on an international stage. Because here’s the thing about hard work: it’s a lot easier to do when you’re not alone.

In 2009, Khalif joined the now infamous team of orange jerseys: Fryz. If Terry and Gaoaen changed the path Khalif was on, then the Fryz guided him down it. Usually Khalif is all confidence and charm: he’s quick to laugh and crack jokes. His bright tone only falters when I ask about what the Fryz mean to him.

“[Fryz] made me more compassionate, it made me kinder,” he said. “It turned me into a social person who likes to make people laugh. It gave me a friend base. It gave me a family I could trust and go to whenever I needed something.”

This family included his teammates, but it also included coaches like Miranda Knowles, Ryan Winkleman, and Pauline Lauterbach Ruegg, as well as Fryz founders Randy and Elana Lim. Together, they helped raise Khalif by giving him the other inexhaustible resource besides hard work: love.

The Lims invited him to dinner when he didn’t have money for food; their home became home for him. The team would spend hours snacking, drinking soda, joking, and plotting their seasons. Once Khalif was at Northwest School, Knowles and Winkleman would host study sessions to help the Fryz kids with their homework. Teammates and coaches drove him home from practice on the nice North End fields so he wouldn’t have to ride the bus for 45 minutes.

“Someone just offering to come pick you up – because they have a car and you don’t – is super important,” Khalif stresses, “and it makes you feel like they want you to get better. Like ‘Hey, I’m going to give you this opportunity to get better, because I care about you as a frisbee player, and I care about you, so I’m going to pick you up.’ That really did matter a lot to me.”

When we talk about ultimate, we talk about the people we meet more than the plastic we throw. We love the thrill of the game, but what we really love is the comfort of community. When Khalif talks about getting hooked on the sport, he talks about competition, jumping high, and running sprints. But sprints aren’t why he stayed. He stayed because the Seattle ultimate community welcomed him with open arms and invested in his growth, both as a player and as a person.

“Fryz gave me a community of people who cared about me, and who were willing to help me with anything,” Khalif recalls. “It was just like a big backbone, especially growing up…” He doesn’t finish the sentence. He doesn’t think about the negative. Instead Khalif finds the bright side. He always does.

“…It made me appreciate what Frisbee does for some people, in terms of changing your perspective on how people treat each other.”

Becoming The Hometown Hero

Terry and Gaoaen were conscious of the disadvantages their kids faced when they left the field. In 2005, when Khalif was at Mercer, fewer than one in seven of the school’s 8th grade students were passing the state science test. These kids came from low-income backgrounds, and they had more obstacles in their way than many of the kids lining up across from them, 70 yards away, with an arm raised.

“When Khalif was in middle school there were very few high-profile ultimate players of color,” said Terry. “In fact Rex and I proactively sought them out to try to introduce our kids whenever possible.”

Thanks in large part to the efforts of coaches like Terry and Gaoaen, and to the success of players like Khalif, a lot has changed. Ultimate is incredibly popular in the South End, and Mercer is thriving.

“Now our kids can see Khalif and others from his class succeeding,” Terry added. “If nothing else it shows that people from their backgrounds can go far in ultimate. People who grew up in the same neighborhoods and went to the same schools and face similar barriers. ”

Khalif has become a hometown hero for kids in Seattle, particularly for kids from the South End. He coaches across the city, trying to give back to the programs and schools that gave him everything. He’s a role model, and he’s acutely aware of the responsibility that brings.

Khalif admits he was a “fiery player” growing up. He’d get frustrated over bad calls, clapping his hands or even slamming the ground if he was upset. He took losses and mistakes hard. But over the past few years, Khalif has realized he’s being watched. His actions matter more.

In his first MLU game, the Rainmakers were down by one point. Khalif got the disc, and turfed it. The Rainmakers lost. Khalif lost it, taking his shirt off and storming to the end of the stadium to be alone. He crumpled in a patch of grass, fuming.

Then he looked up to see a horde of middle school kids leaving the game. They walked by and joked, “Look there’s Khalif. He’s hella pissed.”

Khalif’s reaction was not the example those kids needed to see, and he knew it. So he’s been working to stay positive on the field, cheering for teammates and keeping his cool.

Most 21-year-olds don’t have Khalif’s level of national and international exposure; even fewer share his acute understanding of what this exposure means for his actions. But Khalif knows he represents Seattle, the South End, and the family of coaches, teammates, and players who brought him here.

Progress And Perspective

Next week, Khalif will head once more to the Club Championships with Seattle Mixtape. They’ve enjoyed a strong 2015 season so far, leaving the U.S. Open in July as the highest American finisher, losing to Melbourne Ellipsis — an Australian all-star team — in the final. After finishing second in their Nationals debut last year, the team set its sights even higher this year. And Khalif is ready: he wants to be more than a Cinderella story.

Khalif is also headed back for his senior year at the University of Washington this fall, where as captain he hopes to lead the Sundodgers back to the College Championships – they fell to fourth place in the strong Northwest region last year. But don’t worry, fourth place just means Khalif has a long laundry list of heavy hitters to work through to get to the top.

Khalif can outline the tournaments he wants to win and the heights he intends to reach. But ask some of the people in his life about Khalif, and they tell different stories. Terry remembers Khalif showing up to ultimate summer camp dressed head to toe as Michael Jackson – Khalif is known for being an incredible dancer, and he goes salsa dancing regularly at Seattle’s Century Ballroom. Randy Lim talks about Khalif hanging out in his family’s living room, drinking soda, and laughing. They both talk about the countless kids across Seattle whom Khalif has coached and influenced.

Their stories should be a reminder for Khalif that no matter what his ambitions may be – from becoming the best player in the world to simply breaking seed next week – he’s leaving a bigger legacy than he knows.

The Other Plan

With all of his plans for his future, Khalif doesn’t look back very often. So when I ask what his life would be like if he’d never found ultimate, he has to pause. He takes a deep breath, and he considers deeply.

“I wouldn’t have gone to Northwest School because I wouldn’t have known Sam,” he said. Terry is an alumnus of the Northwest School, a private high school with a long-standing ultimate program. Terry had encouraged Khalif to apply, and he earned a full-ride scholarship.

“I would probably have gone to Franklin [High School]. They’d have a team, but I don’t know if I’d play,” he said. “I’d probably play football.” If he’d played football, he thinks he probably would have been injured. If not, then Khalif muses he may have gone to college to keep playing.

“But if I didn’t…I don’t know. I don’t know if I would have gone to college or not.”

Khalif processes the course of his hypothetical life, step by step.

“I wouldn’t have gone to college; I wouldn’t have gone to Northwest.”

Khalif sighs, thinking. He pauses. Then says, “I probably would have been fatter, to be honest.”

Classic Khalif, breaking the growing tension with a joke. But he doesn’t leave his past just yet.

“I think I would be a completely different person. I don’t know if I would be a classic ghetto person from the South End or if the personality traits I have now would shine through…but I feel like I would be completely different.”

* * *

Would that boy travel around the world to compete internationally? Would he go salsa dancing? Would he have shown up to camps, dressed head-to-toe as Michael Jackson? Would he still be as bright and creative as he is today?

Khalif doesn’t know for sure. He doesn’t dwell on it. He has much bigger things to think about it.