A story of birth, growth, and loss.

May 25, 2016 by Michael Aguilar in Profile with 1 comments

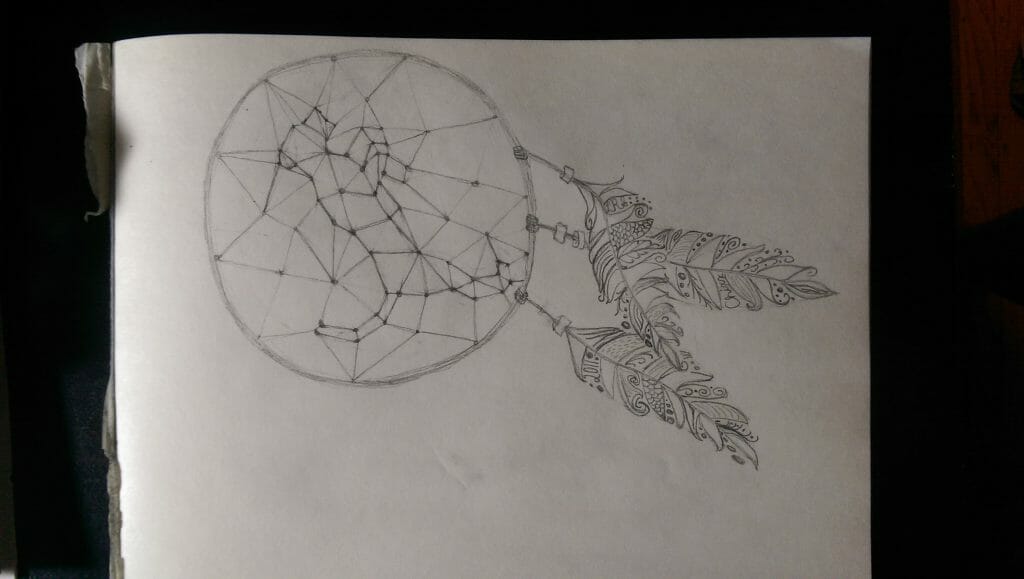

The Native American dream catcher finds its origin in the Ojibwe Nation. The catcher would be made of willow wood and animal sinew, tough fibrous tissue that connects bone and muscle, and hung above an infant’s or child’s bed. The sinew on the catcher collects all sorts of dreams but only bad dreams are unable to escape its web. When morning light strikes the web, those bad dreams melt away, leaving the sleeper with only good dreams to begin the next day.

It’s only fitting, then, that when LSU’s nascent women’s ultimate team and alumni sought a way to memorialize one of its first captains, Lauren Smith, after she died in a single-car accident in November 2015, the dream catcher was a natural symbol. Smith was a resilient, youthful, vigorous, and independent woman, a leader that outwitted, outlasted, and outworked any and all opposition to filter out the botherations of nearly a decade of women’s ultimate depression. And as the proverbial morning has dawned, she has left behind a team and community that will move forward, enriched.

1. The Definition Of Serendipity

In 2010, according to USA Ultimate’s score reporter archive, only seven state flagship universities did not field women’s ultimate teams: the University of Alaska at Fairbanks, the University of Hawaii at Manoa, the University of Idaho, Louisiana State University, the University of Kentucky, the University of North Dakota, and the University of South Dakota.

Of those seven schools, only four fielded men’s teams the same year and only three of those four (Idaho, UK, and LSU) men’s teams participated in the USA Ultimate College Series.

In the fall of 2010, Allyson Lutz — a slight, bright-eyed, often be-pigtailed 18 year old from Nashville, Tennessee, with a dearth of ultimate experience — began her freshman year at LSU.

Lutz had graduated that spring from the University School of Nashville, a small pocket of elite youth ultimate in an area of the country that, at the time, was a one-trick pony in the form of the famous Paideia School out of Atlanta, GA. Her father, Mike Lutz, coached USN’s open team Brutal Grassburn to an Southerns Championship in 2012 and 2013 and she participated on the USN women’s teams that would finish in the top five at the then-UPA’s Youth Easterns Championship every year from its inception in 2005 to 2008.

In 2009, USN did not field a women’s team at the USA Ultimate Eastern Championship, but in 2010, Lutz’s senior year, she and her co-captain, the now household name Jesse Shofner, bullied their way back into the playing field by a sheer force of will and finished tied for 7th.

“It was the day [of the deadline to postmark rosters for Easterns] and we had this plan overnight,” Lutz said. “[Shofner and I] were sitting there and we were like, ‘Okay, we have this girl who says she wants to play. We’re going to get to school early. Meet her in the parking lot. We’re going run down to get her mom to sign the form, and we’re going to run back up to give it to [the school front office] and [the office] will mail it. So it was postmarked the day it was due.”

While many would question the logic and perhaps even the wisdom of someone with such a love of the game voluntarily signing up for a pilgrimage into the ultimate desert that is the Gulf Coast of the United States, Lutz reveled in aspects of the challenge. Even after applying to and being accepted at Cal-Berkeley, Oregon State, and Stanford, Lutz found the scholarship money LSU put on the table appealing and, naively, assumed that ultimate would be something that could easily be managed.

“I kind of realized that it was possible,” Lutz said. “I could build something from nothing even if it was a shit situation.”

However, mere weeks into her freshman year, she was rudely awakened regarding the state of not just ultimate, but women’s ultimate, especially, in Baton Rouge.

After finding receiving no response to e-mails beseeching information from the men’s team contact, Lutz found a rarely used ultimate message board online that, while laden with hidden links to pornography, eventually led her to a rough schedule of when she could find pickup in the area. In her first weeks in Baton Rouge, she made her way out to the men’s pick up scene.

What she was greeted by was the trademark of LSU Ultimate at the time, a pack of tall, veteran players with a culture1 that made the 5’6″ Lutz feel out of place for more reasons than the fact that she was the only woman at pick up.

Lutz attempted to pursue community outside of practice, consistently finding herself timidly approaching strangers around campus asking if they were interested in ultimate frisbee or had played before. While occasionally getting feigned interest or the kind but offensive inquiries about disc golf in return, she was also met with scorn and spite on occasion, leaving her optimistic spirit mildly crushed.

“I had the reoccurring thought of ‘What the hell have I done?’ throughout my time [at LSU], up until the last day of sectionals my senior year,” Lutz said.

The only thing that kept that question from being the dominant thought of Lutz’ mind came in the form of what she would later refer to as “the definition of serendipity.”

Eventually, Lutz’ previously ignored e-mails were answered by Laura DeLatin, an LSU student and Baton Rouge area player who had been involved in the sport since high school. DeLatin had been a part of an unsuccessful effort to get an LSU women’s team off the ground in years past. DeLatin gave Lutz a primer on women’s ultimate in Baton Rouge, or the lack thereof, and also copied in another e-mail address that Lutz didn’t recognize.

DeLatin’s olive branch and the thought that there was possibly another girl interested in women’s ultimate on campus was enough to keep Lutz going to pickup but, a few weeks into her freshman year, dreams started to manifest in reality.

Lutz found herself walking between orientation events in stride with a tall, blonde environmental engineering classmate. They struck up a conversation and quickly found a lot of common ground, from the fact that they were both out of state students to their mutual desire to preserve the environment. Unfortunately schedules took them in separate directions but Lutz was encouraged.

“Oh cool! I met this awesome friendly person who I’m probably never going to see again because this school is giant,” Lutz recalls thinking to herself. “It was nice to talk to somebody nice.”

Bigger things were in store for Lutz and this classmate, though. On the first day of actual class, Lutz hurried to Calculus and unknowingly plopped herself down in a desk right next to that same tall blonde. It was then, in that classroom, that Allyson Lutz really met Lauren Smith for the very first time. It was also then that their paths became inextricably linked and the foundation began to be laid for the formation of a program.

2. They Were Audacious Enough. They Didn’t Care Who They Were Playing Against.

The first few interactions of Lutz and Smith’s relationship passed by without spectacular incident. They talked often and walked to and from class together. Smith became a rare friendly face for the shy and, at times, downtrodden Lutz.

Lutz was still attending men’s pickup and even men’s practice but, with the hostile or apathetic reception she was getting while trying to find other women interested in the sport, she was starting to lose some measure of hope that she once had for her collegiate ultimate career and, by extension, her collegiate experience in total.

However, Lutz found in Smith what most people found in her. Smith stood about 5’8″ and was an imposing presence, but she could quickly disarm you with an easy smile that was just-not-quite-perfectly-straight that indicated something between mischief and joy. She was quick to offer a joke no matter how bad it was and even quicker to lend an ear to any problem you may have. On top of all it there was an intensity behind her eyes that made it clear that she was operating on a level of sincerity in all things that many people struggle to reach in their most passionate pursuits.

Perhaps it was that sincerity that led Lutz to test the waters with Smith about ultimate frisbee. When Lutz finally worked up the courage, the response was beyond her wildest dreams.

“She just turned to me and she goes, ‘Oh my god I love ultimate frisbee!” Lutz remembers Smith’s reaction. “I was just like, ‘Wow.'”

Quickly Lutz and Smith put together that they each were the other unknown e-mail address that DeLatin had included in her informational e-mail a week or two before. In an unbelievable twist of fate, the nameless, faceless entity that had been providing Lutz with the hope that she needed to carry on trying to find an ultimate home had finally been given form in Lauren Smith.

It turned out that form was precisely what Lutz needed to feel at home in Baton Rouge and on the field with LSU’s men’s team. It was from that point on that, at least in the ultimate part of their lives, the two were inseparable. If Lutz was at practice, Smith was at practice. When LSU’s first fall tournament, scheduled to be in College Station, TX, came around, Smith was unable to attend; with the counsel of her own mother, Lutz decided to sit it out as well.

Despite missing the first fall tournament, their regular presence at the men’s practices had started to raise some eyebrows. Unbeknownst to Smith and Lutz, their determination and grit was making waves with many characters in the Baton Rouge and LSU ultimate community, some of whom would later be pivotal role players in the formation of the women’s team.

Among them were Nick Hwang and Tim Lala. Hwang, now a professor and coach at University of Wisconsin-Whitewater, would later become one of the coaches of the LSU women’s team. Lala, a sophomore at LSU during Smith and Lutz’ freshman year and now a high school football and basketball coach at Catholic High School – Point Coupee in Point Coupee, LA, would eventually captain the LSU men’s team alongside Smith and Lutz’ maiden voyage into captaining the women’s team.

“I thought it was a great idea that they were audacious enough, that they loved the sport enough that it didn’t matter if they were playing with women or with men,” Hwang said. “To me it was great, they obviously didn’t care who they were playing against.”

“After having worked with them for a while,” Lala said, “it was clear pretty early on that they were going to get their stuff together.”

Over time Lutz and Smith inserted themselves into the fabric of the LSU scene. Though Lutz began to gain confidence on and off the field, it was through Smith’s vibrant contributions to the team that Lutz really felt that they began to find their place on the B team.

“Lauren was just the type of person who was friends with everybody, instantly,” Lutz said. “So she made friends with the guys and they thought I was cool too so I was like, ‘Awesome.'”

Even still, as they played and practiced with the men’s team it wasn’t until they attended their first tournament together that Smith and Lutz friendship began to crystallize as something deep and lifelong. The two rode to Starkville, Mississippi, in 2011 for the Cowbell Classic, a tournament that went down in infamy in the Gulf Coast ultimate scene. Suffice it to say, in this space, that by the time the dust had settled, one LSU player had been banned by the school from competition for the year.

Welcome to college ultimate young Allyson Lutz.

“That’s my best college story as far as crazy things that happened,” Lutz said. “I was so thankful to have another girl there. She had the clarity of mind to check on me when I was taking care of some guys and make sure I was okay. I felt a lot of camaraderie of, ‘Oh my gosh, these guys.'”

After surviving the trip, Lutz and Smith were emboldened and that sense of camaraderie started to spill over to their everyday lives. Soon enough, Lutz’ hallmates had started attending men’s B team practices, Smith had recruited a friend, and a girlfriend of one of the men’s team players had showed some interest as well.

With the addition of DeLatin, who hadn’t been interested in participating with the men’s team, there were seven girls committed to playing women’s ultimate on campus — a full line. The deadline to put in a bid for Conference Championships was fast approaching and Lutz was having flashbacks to her bedroom in Nashville as she and Jesse Shofner schemed about how to persuade some unwitting accomplices into letting her and Shofner drag them to a 7th place finish at Easterns.

This coven of women’s ultimate met where all good ideas come to fruition in college — in a dorm stairwell — to discuss the feasibility of taking a women’s team to Conferences. Ideas were passed back and forth and a few things were agreed upon, Lutz took notes and here, without edits, are the bullet points of some of the decisions that those seven were able to agree to:

- Going to tupelo (location of men’s Conference Championships in 2011)

- No babies till marriage/civil union

- Must watch mean girls once a semester

- Club in the fall

- Girls

Most significantly apparent from this document are that there was a single-mindedness about a lot of things. The girls agreed that traveling with just seven players and no subs for their very first tournament was not the foot that they wanted to set out on. They also agreed that they would be a club in the fall. Though some of the players present at that meeting would come and go in the future, these seven established a precedent that had not been realized at LSU for some time: they were going to make a women’s team.

3. We Set Out to Accomplish Something and We Did

When the fall of 2012 arrived and Lutz and Smith sought to embark on the journey of beginning their team, they had no idea that they were up against some serious history. Again, two years before, LSU was one of only three state flagship universities that did not have a women’s team but did have a men’s team competing in the USA Ultimate College Series.

LSU had fielded a women’s team from the years of 2004-2007. The team, in that iteration, played few games (only one listed in 2007) and performed less than admirably; it’s banner year from that period came in 2006 with a 2-4 record, the two wins coming over Louisiana-Monroe, another Louisiana school that no longer fields a team, and the four losses coming by a combined score of 4-43.

So what happened? Well, that’s where history starts to get fuzzy. Neither Hwang, who moved to Baton Rouge in 2006, the last year that LSU fielded a women’s team before Lutz and Smith got involved, nor anyone else in the LSU community will get much more specific than the word “drama.” In Hwang’s opinion, at least, a fear of a women’s team interfering with the men’s team’s goals was certainly something that played a role in creating the void that existed through 2012.

“One of the factors that prevented the women’s team from ever reformulating was that there were members of the men’s team that had discouraged it,” Hwang said. “There were some people that put forth their best efforts to put down the women’s efforts to form [a team]. They didn’t have the help of the rest of the community to formulate one.”

Hwang saw Smith and Lutz’ time on the men’s team as a key factor to breaking through the barrier that existed from 2006 to 2012.

“They knew that they didn’t have enough women but they wanted to play and until they had enough women to splinter off and officially form the women’s team they were perfectly fine playing with the guys,” Hwang said. “Thankfully, the climate around 2011-2012 and years leading up to it had changed and it was okay with the guys to have women around. Up to that point, I felt like there were persons in the community that didn’t view them as equal athletes.”

As if battling half a decade of resistance from the community itself wasn’t enough, Lutz and Smith were also battling geography. That was a battle they were fighting on two fronts.

On the one hand, the Gulf Coast existed as an abyss of ultimate for a significant period of time from the early 2000s (after LSU’s men’s team had made a Nationals run or two and hosted a Callahan winner, Brian Harriford, on its roster) until just last year, when Auburn finally qualified and returned the Bama Section to the national stage.

“Not only were there no [competitive] women’s teams in Louisiana,” Lala said. “The closest [men’s] competition was Southern Miss and we were beating them handily any time we matched up with them. I think how much [ultimate] was lacking notoriety at the time was a pretty big factor [in the lack of a women’s team].”

On the other hand, their battle was against the South, an area of the country that is just as known for its hospitality and grits as it is for its backwardness and antiquated ideals. Both Smith and Lutz, at least in part, grew up in the heart of southern culture.

“This is the thing that I’ve held on to,” Lutz said. “Obviously, I don’t have statistics. I only have my own perspective to speak on. It’s kind of this Southern stereotype of a ‘polite southern woman and what she’s supposed to do.’”

“I don’t think that Ultimate falls into the category of sports that are girls’ sports,” Lutz said. “Atlanta is a hotbed of ultimate and they’re in the South but they have those awesome feeder schools, like Paideia and a very strong community that helps develop that area into a community that accepts ultimate and women playing. There’s a void of that in Mississippi, Alabama, and Louisiana. There’s an idea that there are sports that are okay for women to play.”

And ultimate, with its grassburns, men in skirts, women in long shorts, and lack of ribbons is not one of those sports that many in the South consider to be the “women’s sport” that Lutz refers to.

When up against six years of embedded and active resistance, a desert of competitive ultimate at any level from youth to club, and stereotypes that dictate what is and isn’t okay for your gender to do, one does not just simply start a team. Rather, as Lutz soon found out, one fights for a team. Fortunately for her, she had Smith by her side to do that dirty work.

“Lauren was looking for a fight every once in awhile,” Lala said. “I think that’s a lot of the reason that she ended up reaching her goals. She didn’t care what the perception was.”

Smith wasn’t just interested in the fight though. It would be easy enough to say that she and Lutz were able to create a team because they broke the mold in the most dramatic way possible but there was more to it than that. Smith, especially, broke the mold because she refused to live on one end of the spectrum or the other. One minute, she fought the geography and resistance in front of her; the next she attracted women from a more traditional paradigm because she walked such a fine line.

“We’d get home from practice — and you never look worse than when you get home from practice or home from a tournament on Sunday night — then the next day we’d get up and Lauren looks like a supermodel,” Lutz said. “She was fantastic at doing makeup and had an amazing sense of fashion. She was like a girl’s girl during the day and at night it was like, ‘time for frisbee.’”

This dual life of sorts was key to the recruiting efforts of Lutz and Smith in the early days and those around them took notice. The newfound LSU women’s team rolled towards critical mass.

“They got a ton of girls out,” Lala said. “It was really unbelievable when they were getting it rolling, the amount of people they were able to attract. It’s always an issue with recruiting and retention. You can always get a ton of people out but if they felt like it was too much for them or too much was being asked of them they’ll drop like flies. That never happened for them. They created a culture that girls wanted to be a part of.”

Suddenly, with a team on their hands, Smith and Lutz were caught up in the day to day of taking a group of young athletes and creating something tangible out of them. Practices came and went, tournaments were played, games won and lost. Inside of all of it were beautiful moments like a Thursday night before Conferences, when, at the eleventh hour, someone realizes that the black shirts you bought from WalMart as jerseys aren’t holding the color of spray paint that you bought.

It was in all of these moments that Smith and Lutz formed a friendship of immeasurable worth. If it wasn’t Lutz stepping to the plate, it was Smith. It was on that warm, late April night under the yellow-orange glow of on-campus sidewalk lights that Smith arrived with paint in hand and drew, by hand, the logos and numbers on every single jersey. Finally, with the end of season in view, Lutz was able to reflect on things that had come to pass.

“It was just this moment of looking around and saying, ‘Holy shit, we’ll have jerseys,’” Lutz said. “I know they’re just spray painted cotton t-shirts from Walmart but a year ago we were sitting around talking about how there wasn’t enough of us to even talk about doing this.”

So it was moments like those for Lutz, and probably for Smith, that stuck out the most. It wasn’t about wins and losses. In this instance, it was about something much more significant. So perhaps it’s no surprise that, with her arms around her teammates’ shoulders taking the last team picture of her college career a ton of bricks landed right on her chest and she struggled to smile through many tears.

“That moment of taking a team picture at Sectionals, which was the last tournament I played with LSU women’s team,” Lutz said. “It was this weight had been lifted off my shoulders. We set out to accomplish something and we did. I wouldn’t trade the last four years for anything. Not a thing.”

4. She Deserved to See This

Perhaps all these memories are worth preserving on their own. Against all odds, two girls bonded by friendship, serendipity, love for a game, and one another created something from nothing. Sure, it’s been done before and it will be done again. Ultimate teams are started all over the country every year.

However, when Smith passed away last fall, this story lost one of its authors. So some sense of urgency must be felt to tell it. Some recognition that, without one of its voices, it is incomplete. Perhaps that recognition is why those who can still tell it are able to so vividly recall that voice. Perhaps that’s why they remember Smith so clearly, and so fondly.

To Tim Lala, it almost seemed natural. Though things were so stacked against them, Smith and Lutz fit together so well and recognized their roles so early. That the only natural conclusion was that a team would be formed and arise.

“For Allyson I think it was the love of the game,” Lala said. “She had been brought up in it. For Lauren, she was the type of girl that was passionate about whatever she was doing. She had a tremendous impact on a lot of people. She was just relentless. She played relentlessly. She was going to find a way to make it work no matter what obstacles they were going to face.”

That relentless love that was present in both of them manifested itself so clearly in the building of a team that existed for a purpose beyond being the team with the higher score when the hard cap sounds.

“Once they did have that many girls they were speaking for they knew they had to do it for [those girls],” Lala said. “The passion with which they led those girls was tremendous. They created this team, this group of young ladies that just loved being around each other with the common goal of starting a successful program but that was secondary to the culture they created with those girls. When they realized that it was more than just them two against the world and they were representing something bigger, when they realized that they were really unstoppable.”

To Nick Hwang, it’s obvious that Smith and Lutz’ impact will outreach any scope of what either of the two could have ever conceived.

“I think maybe Allyson and Lauren didn’t exactly know how much their efforts would expand and touch people that they may have never met,” Hwang said. “Now there are women’s teams and Baton Rouge Summer League is much more mixed now and opportunities and chances to get involved have more than doubled I feel.”

When it comes to Smith, though, that is the way things were. Her reach wasn’t limited to this moment or that throw or this party or that conversation. She had a spirit that effervesced beyond a particular moment or situation.

“I just remember her as full of energy, really positive, and someone that attracted other people to her and to each other,” Hwang said. “I don’t think that there was a time that I thought about Lauren that I didn’t imagine her being in a room full of people and everyone enjoying her and each other. That’s the type of person Lauren was. She was just loving life and that’s genuinely how I remember her.”

Then it should definitely come as no surprise that, even though Smith finished at LSU in 2014, her name still resonates with many on the team. Among them are Kelly “Bernie” Barnett, who first met Smith as a freshman in the fall of 2013, during Smith’s senior year. Barnett was struggling through her freshman year and Smith appeared not just as a team leader for Barnett but as an emotional one as well. All of this leads to Barnett to talk about the LSU women’s program with some pretty clear terms.

“Honestly, though, the LSU women’s team, it sounds cliché but it’s appropriate to say, is my family,” she said. “Particularly Lauren, Lauren was very much big sister to me. My spring semester of my Freshman year she took me under her wing and helped me through not only the frisbee season but my personal life as well. If the team wasn’t here I don’t know where I would be.”

With a relationship like that, it’s no surprise that Barnett now misses Smith’s presence.

“I wish she was here to see how the team is progressing,” Barnett said. “On the whole, considering we did lose our founders and a lot of the initial players, we’re doing alright.

It’s a wish that she shares with many. Most notably, Allyson Lutz.

Talking with Lutz about Smith is a difficult prospect. You don’t make it far before Lutz gains a notable quiver in her voice. It’s not that you blame her. It’s just that you realize, before you get far in the conversation, that she’s talking about something a little bit different than what you’re used to. That maybe the way she feels about Lauren Smith isn’t quite the way that you feel about your best friend.

Because, once you build something together, once you accomplish something notable, once you’ve filled out one hundred forms that all say the same thing, “Yes. We’re sure we want to start an ultimate team,” once you’ve shamelessly walked up to strangers and attempted to convince them that, yes, chasing a plastic children’s toy is a competitive goal worth seeking, once you’ve taken graduation and wedding pictures together, once you’ve lived together, once you’ve truly been a team, you’ve got something a little bit different than everyone else.

“[I wish people could see] the tears that she cried in anger and frustration,” Lutz said. “The sweat that she put in at the gym when her team was frustrating her. The blood that she had from scraping her butt up on the grass. That she isn’t going to see that pay off the way that I know it’s going to and the way that it has. There are a lot of girls that are going to find a space at LSU and that is because of the stuff that Lauren did.

“Obviously besides the loss of a friend and a daughter and a sister and all the important things that she was, as far as the Ultimate team is concerned we lost a great leader and a really loyal teammate who’s not going to get to bask in the glory of all the cool things she put together. I feel like she deserved it and people don’t realize just how much went into it. She put in her own money, she organized places for us to stay, she made sure that bid money got in on time so that we could actually play in these tournaments, she helped make sure the paperwork got in on time. When I was a mess and stressed out she … She did a lot. The ultimate team would not be a thing without her and that’s really important to know. It sucks, she deserved to see this.”

Those that are left behind, especially in the ultimate community, now remember her by the symbol of the Dream Catcher, printed onto jerseys. It’s a fitting symbol. Smith was a literal Dream Catcher. For years, many missed on the experience that is college ultimate. However, she and Lutz dreamed of a possibility that may have, at times, seemed impossible. But Smith’s relentlessness, energy, positivity, aggressiveness rose above. Lauren Smith did the impossible. She caught that dream, trapped it, bottled it, and helped share it so that many to come will find in it the joy that she did.

Correction: An earlier version of this article misidentified Laura DeLatin as Lauren Delatin. We apologize for the error.

for reference, see this post and the comments ↩