Home and away -- or forehand and backhand?

November 25, 2020 by Guest Author in Analysis with 0 comments

This article was written by Steven Weisberg, an Assistant Professor of Psychology at the University of Florida.

Success in ultimate requires teamwork. At any level, individual greatness will be quashed by ineffectual team play and, perhaps most critically, ineffectual communication. Complicating matters, ultimate requires spatial communication – who needs to be where, facing which direction, and forcing throws toward which side of the field.

If you’re wondering about the difficulty of communicating spatial information, consider the last time you discussed strategy or taught a defensive scheme. Did you use a visual aid? Rocks and sticks, a white board, physically posing players around the field: at the very least, did you gesture or use your body? Communicating spatial information verbally is difficult!

Yet on the field, verbal communication is all we have time for, along with perhaps an urgent gesture. But getting communication correct is critical! If a defense establishes a home force, and everyone but one player gets it right, you may as well concede the point.

So isn’t it odd that for a major defensive scheme – the force – there are two main ways of referring to it? Why do we (redundantly) say “force forehand / force home”? The answer to this question is because of what are called in the cognitive psychology literature spatial reference frames.

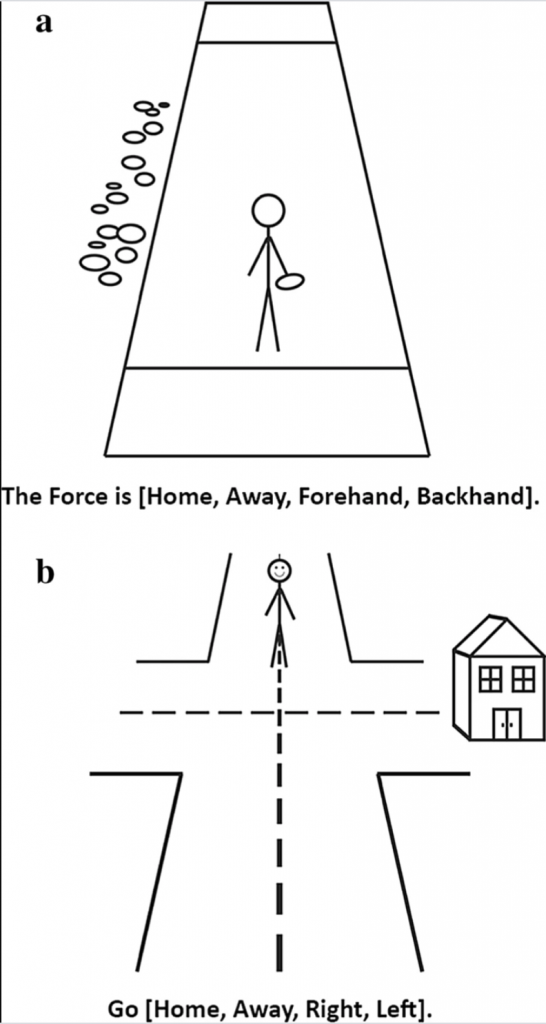

Spatial reference frames are coordinate systems which can be used to define spatial directions. A common example of a spatial reference frame is compass directions. We can use North to define the directions around us. Compass directions are an example of an environment-centered reference frame, defined with respect to something in the environment. Environment-centered spatial directions keep the same value relative to North regardless of which direction you are facing.

On the other hand, we could define a spatial direction with respect to your own facing direction. We could, for example, tell someone to turn right, which would lead them 90º to the right of the direction they are currently facing. These body-centered reference frames do change relative to environment-centered reference frames: if you spin around 180º and then turn right, you’re facing the exact opposite environment-centered direction, even though you turned right in both cases.

In spatial navigation research, these two reference frames are supported by two distinct neural systems, which vary widely in their use across cultures and even across people within a culture.

But what does this have to do with ultimate? Think back to the force. Calling the force as ‘home/away’ uses an environment-centered reference frame. (Does it matter which part of the field you’re on to establish a home force? No – it’s always to the home side of the field). Calling the force as ‘forehand/backhand’ uses a body-centered reference frame.

Anecdotally (from my own experience as a player and captain, having taught ultimate to mostly intermediate and novice players for over 15 years), it seemed to me that players A) have difficulty understanding the force, and B) have strong preferences for how they prefer the force called. For myself, I strongly prefer the home/away version of the force; but I’ve talked to players who feel equally strongly about the forehand/backhand version.

As a cognitive neuroscience researcher who studies individual differences in spatial navigation (see my website for more, like, why do some people get lost more easily than others? and how does the brain converts verbal information into spatial representations?), this variation in preference for calling the force struck me as similar to variation we see in preference for spatial directions in navigation tasks. Some people prefer a North/South direction scheme, whereas others will get lost without left/right directions!

But what do the data say? In an online behavioral experiment, we recruited 58 experienced ultimate players to complete two versions of a spatial reference frame task. In the task, they viewed simple line drawings of a stick figure and had to indicate either which direction the stick figure would go on a road intersection, or which direction the stick figure would be forced on an ultimate field.

We predicted that players would be faster using the reference frame they preferred, and that this advantage would be comparable for the spatial navigation and the ultimate contexts. This is not what we found. Rather, we found a large effect of context! In the ultimate context, players were faster for the forehand/backhand trials compared to home/away. In the navigation context, players were split – roughly half were faster for right/left and half were faster for home/away.

These data are important for how we think about spatial reference frame preferences across a wide variety of tasks. For ultimate, they suggest that experienced players might be more adept at processing force schemes using forehand/backhand cues.

But our findings are just scratching the surface of this issue. How do spatial reference frames evolve as a player learns ultimate? (Our player participants had an average of eight years of ultimate experience). Is there a more effective way to teach ultimate as a result? Are our result moderated in some way by the task we used? It’s not unreasonable to think that players pressing buttons on a keyboard does not completely reflect their proficiency on an ultimate field.

Of course, our results may not matter for experienced ultimate players at all – once they spend the 1-2 seconds translating the force into their preferred reference frame, there’s no lag at all. (Although I’d wonder if this lag is more costly if the force needs to be switched mid-point or mid-throw?)

Still, I believe this work provides some critical data for an understudied area of spatial cognition (and ultimate)! The old adage that sports are 90% mental may be pure gossamer; but how we tune our minds to play sports is no doubt some part of the equation.