Hucking into the wind is hard. But understanding the physics of throwing a disc can help you carve out an advantage.

August 13, 2014 by Benji Heywood in Analysis with 8 comments

How high do you want your release point when hucking?

That’s actually a really complicated question; unsurprisingly, the answer is, “It depends.”

**This piece is a follow-up to Benji’s earlier (and popular) article about Spin v. Wobble when throwing in the wind. If you enjoyed this post and want to hear more, view Benji’s talk at the URCA Conference next week.**

You could argue that for maximum distance a higher release is best, all things being equal1, as the exact same throw from a little higher will stay in the air that fraction longer. Also, if there’s a particular height you want to achieve in order to get over any defenders between you and the receiver, starting higher means you need less of an upward angle to achieve that height – and clearly a less steep angle will waste less of the disc’s horizontal speed.

On the other hand, you might be much more worried about how long the disc ‘sits’ at a catchable height — for a receiver to chase down — than about maximal distance, in which case throwing with the front edge tilted upwards may be beneficial. Tilting the disc up will give the disc more lift, and slow it down more rapidly, as the bottom of the disc hits the air; this will give your throw that easily-caught low-speed float at the end. To make this adjustment work, though, we might have to start the throw from a bit lower, otherwise having the front-edge lifted may balloon the disc too high overall.

And of course, there’s the marker to worry about too – you might not have a completely free choice of how high or low you release your throws. You need to practice all the different options. There’s really no answer beyond, “It depends.”

Except sometimes there is.

When hucking into a significant wind, there’s a clear and demonstrable advantage to throwing from low. You’ve probably discovered or been told already that throwing into the wind is easier from close to the ground.

But why is that? There are two factors: one is the wind profile, and one is the wobble-damping I discussed in a previous article.

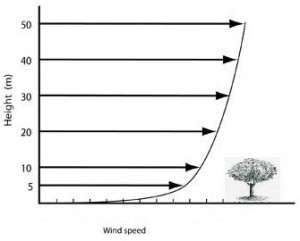

Firstly, the wind. Wind strength is not the same at different heights above the ground. You’ve probably experienced this first-hand, both in ultimate and elsewhere. It’s not that windy near the ground; when you throw a high, floaty hospital pass, you can see the disc is much more affected by wind. And standing on top of a mountain is a great deal windier than at the bottom.

The ground itself creates drag and slows down the wind. As you get lower, there’s more stuff in the way, and that applies not just to shelter provided by trees and buildings in the distance, but also to something like the grass on the pitch itself. The grass only slows down the air right next to it, but that slow air in turn slows down the air just above that, and so on. There’s drag all the way up, and so you’ll almost always find that the lowest wind speeds occur near the ground2.

The ground itself creates drag and slows down the wind. As you get lower, there’s more stuff in the way, and that applies not just to shelter provided by trees and buildings in the distance, but also to something like the grass on the pitch itself. The grass only slows down the air right next to it, but that slow air in turn slows down the air just above that, and so on. There’s drag all the way up, and so you’ll almost always find that the lowest wind speeds occur near the ground2.

How does that help us? We’re not generally trying to throw something which stays a foot from the ground for the whole flight, meaning that at some point the disc will be exposed to stronger winds. So why is a low release so much better?

Remember that most of the wobble we put on the disc at the point of release3 will settle down quite quickly (provided we generate enough spin). So there’s a significant difference between a disc released low, in lesser wind, and one released in the stronger wind higher up, even though both eventually end up at the same height. Only the low release has time to smooth out its wobble before hitting the worst of the wind. And as we discussed in the previous article, wobble combined with high airspeed will flip the disc.

So two throws released with equal flutter will behave very differently based on whether they are thrown from high or low. You’ll still of course benefit from throwing more smoothly and with more spin. But for every thrower, no matter how good, a low-release throw will cope better into the wind than an otherwise identical higher-release throw.45

The overall message: discs thrown from lower will flip over less into the wind than those thrown from higher, provided that your low release isn’t wobblier or otherwise less controlled. If you’re throwing hard into the wind – hucking – or if the wind is very strong, you may need to pay attention to where you release the disc. Experienced handlers make these choices automatically – now you know why.

That wind profile has an important repercussion downwind also. The lift on the disc is a function of its airspeed, of how fast the air passes over the surfaces of the disc. And a disc traveling with the wind – even if it’s traveling quite fast relative to the thrower or to the pitch – won’t be traveling very fast through the air. So the disc has very little lift, and tends to drop like a stone.

But often, right at the end of its flight, it will just stay afloat that fraction longer than you expect. Where did that come from?

A disc flying downwind won’t experience much drag. It will be moving at a similar speed to the air around it, meaning there’s nothing to slow it down. So at the end of its flight, as it drifts lower, it will still be traveling down the pitch quite fast. If it drops to a height where there’s significantly less wind, so that it’s now moving much faster than the air around it, it will suddenly generate much more lift. Very often, a downwind disc that appears to be about to hit the ground will seem to get a surprise little extra float at the end.

This is not the time to bemoan how unlucky you are, that after you gave up on the disc it surprisingly decided to float a little longer; rather, this is predictable, consistent behavior that you should be expecting if you understand the wind profile near the ground. Don’t give up chasing discs downwind unless they’re really out of reach.

Basically, playing in the wind is complicated. There are some consistent truths, but few easy answers — it’s no surprise that experience wins on windy days. Get out there and throw when you can.

If you’re interested in this sort of technical analysis, check out the Ultimate Results Coaching Academy conference. I’ll be giving a talk on technical aspects of throwing. And even if you don’t want to listen to me ramble on, a whole host of amazing speakers — Ben Wiggins, Tiina Booth, Gwen Ambler, Tim Morrill and many, many others — will be talking about a huge variety of topics. And it’s all completely free! Go take a look.

For example, the point doesn’t stand if you release so high that your mechanics are impaired. ↩

I could only find one paper discussing this which had data from useful heights – most deal with the wind profile up to at least 50 metres from the ground, talking about the placement of wind turbines or the effect on air travel and such. This paper however had data at 10cm, 1m and 2m above the ground, and found that on average the wind was more than 50% stronger at about waist high than at 10cm; and nearly two and a half times stronger at head height. In stronger winds, I’d expect the effect to be even more pronounced. (For the windiest half of their measurements – still only around 10mph winds – the figures were 67% stronger at 1m and nearly 3 times stronger at 2m. That suggests to me that the gradient would be even stronger in 25-30mph winds, which certainly matches up with my experience on windy days.) ↩

We can’t completely eliminate wobble, by the way, no matter how smoothly we throw. The disc is quite pliable so, as we accelerate it, it will deform under its own inertia and there’s no way we can release it ‘flat’ – even if it spins in exactly the right plane, the misshapen disc will be wobbling at the edges. ↩

Note again, of course, that this only applies if your mechanics are not otherwise impaired. If you throw better from knee height than from very low, you may find, even in a strong wind, that knee height still suits you better. But if you could throw the same thing from very low, it would undoubtedly cut through the wind that little bit better. ↩

Note also that there may be other disadvantages to throwing from low, and on gentler throws (that won’t flip over too much anyway) you may be better off throwing from waist-high. For example, a low-release, upwards throw shows the bottom of the disc to the wind, making it more likely to pop over the receiver if hit by a sudden gust; often for shorter throws it’s better to throw flatter, from higher up. But for a more powerful throw, or in a really powerful wind, the problem of trying to prevent the disc flipping overrides other issues. ↩