August 26, 2015 by Charlie Eisenhood in Opinion with 12 comments

In 1982, Irv Kalb and Tom “TK” Kennedy published the first-ever book about ultimate, titled “Ultimate: Fundamentals of the Sport.”

As you might imagine, Kalb and Kennedy were both Hall of Fame locks, and were both enshrined in the Hall in its inaugural year, 2004. Kennedy was the founder of the Ultimate Players Association and its first-ever Director. He also founded the Santa Barbara Condors and won numerous National Championships in his time as a player.

Kalb was perhaps the first big star on the East Coast. He captained Columbia High School in the early 1970s to an undefeated season and then dominated as a player at Rutgers from 1972-1976, finishing his career there with a record of 45-1. He helped develop the rules throughout the 1970s.

Many books and articles have since been published about ultimate and its strategies, tactics, and history, but theirs was first. The book remains surprisingly relevant — although it is light on in-depth tactics, its general approach to the game and the styles of offense and defense is still widely applied today. Here are some of the most interesting moments in the book.

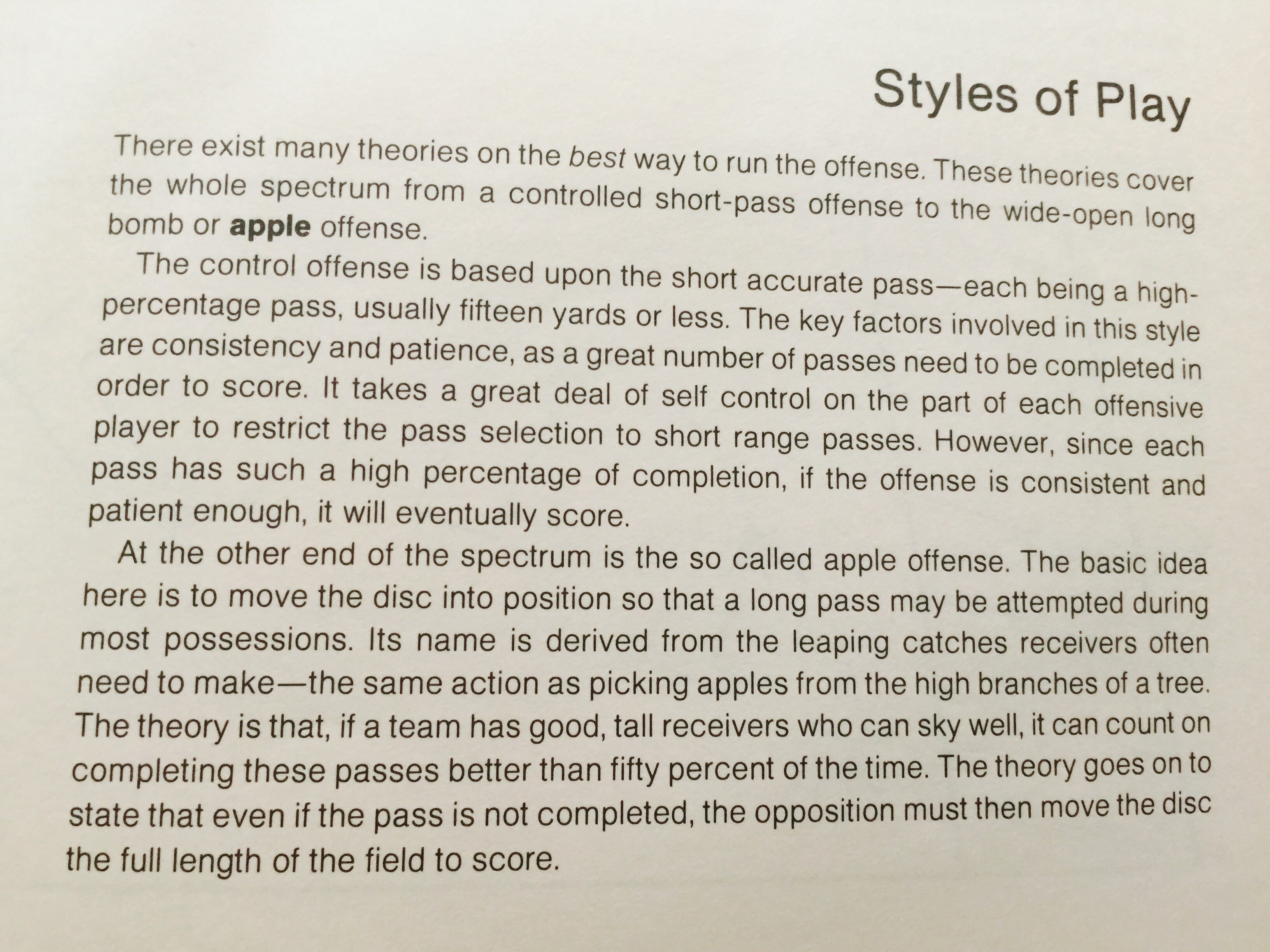

1. The prevailing offensive theories haven’t changed much.

After outlining the above, the book goes on to describe the “flow offense,” a middle-ground between the two above theories that stands as the most widely-used approach among teams today. “The basic idea behind the flow,” they write, “is to complete passes in rapid succession by having receivers make proper cuts in sequence while the disc is moving downfield.” The concept of continuation cuts is right there, even if it is not named as such.

I think Atlanta Chain Lightning, instead of saying they run a huck-heavy offense because “chicks dig the long ball,” should instead say “an apple a play keeps the losses away.” OK, I’m reaching.

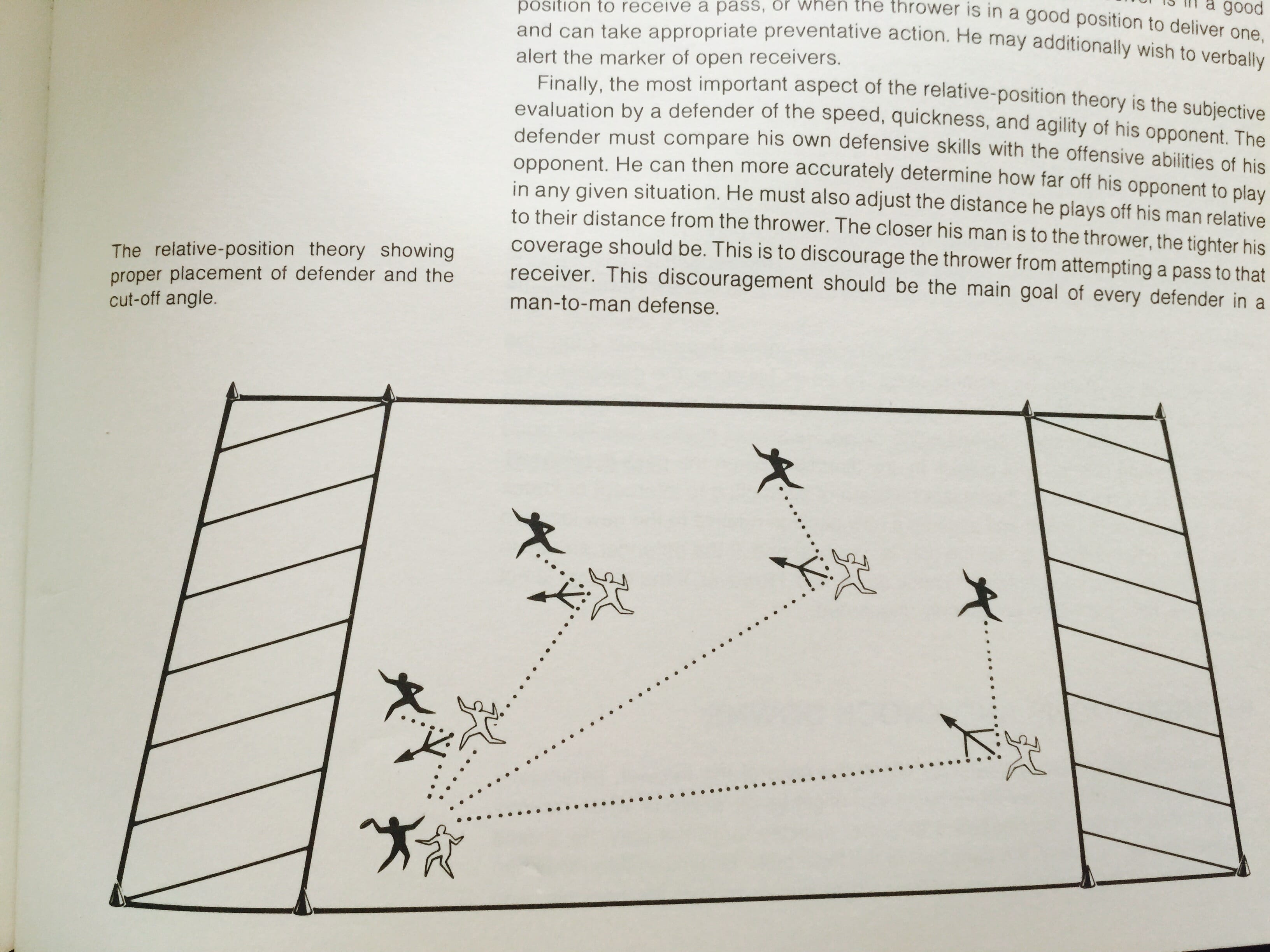

2. The Relative-Position Theory of defense is fascinating.

I had never heard of this concept until reading the book. And I’ve never seen the idea presented that you should always form a ninety degree angle between the receiver you are covering, yourself, and the thrower (as illustrated). The idea is that you have a “cut off angle” to make a play on the disc and maintains sight lines and proper alignment to guard the open side of the field.

There is some very good material in the book about key man defense concepts, like constantly repositioning, staying in visual contact with both the thrower and the receiver, and comparing your speed/quickness/agility to that of your mark and cushioning as necessary.

It also mentions fronting defense as a tactic, though it points out that it makes you “more susceptible to being beatn by a longer downfield pass.”

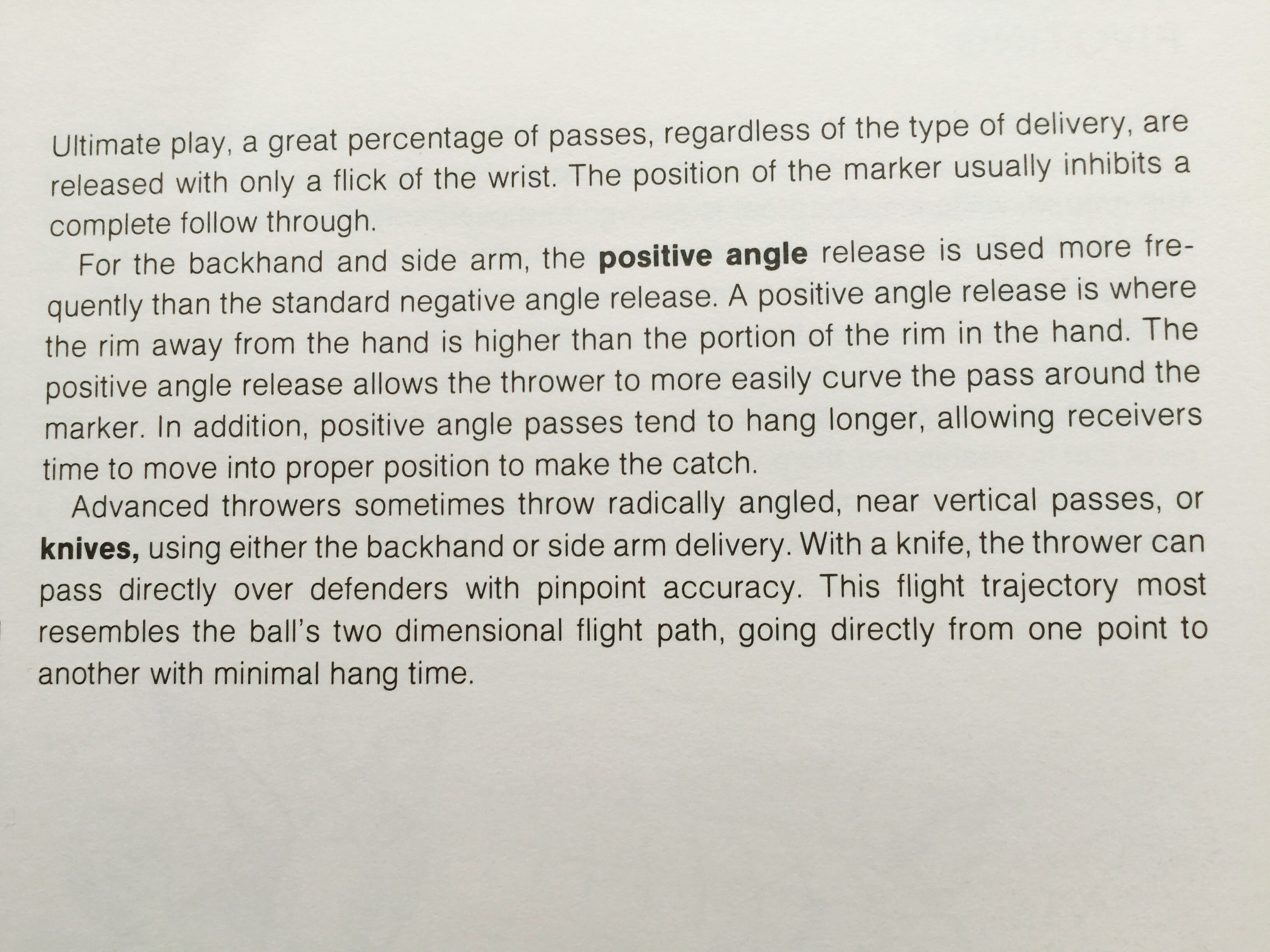

3. Blades used to be called knives.

The terminology in ultimate has changed a lot since the ’70s. There were no references to a forehand or flick (called a sidearm in the book), throwing a huck is never mentioned (instead, long pass), and a pancake catch is called “clamping.” But surely the most surprising term was “knife” to describe a vertical pass.

Oh, and sky? It’s in there.

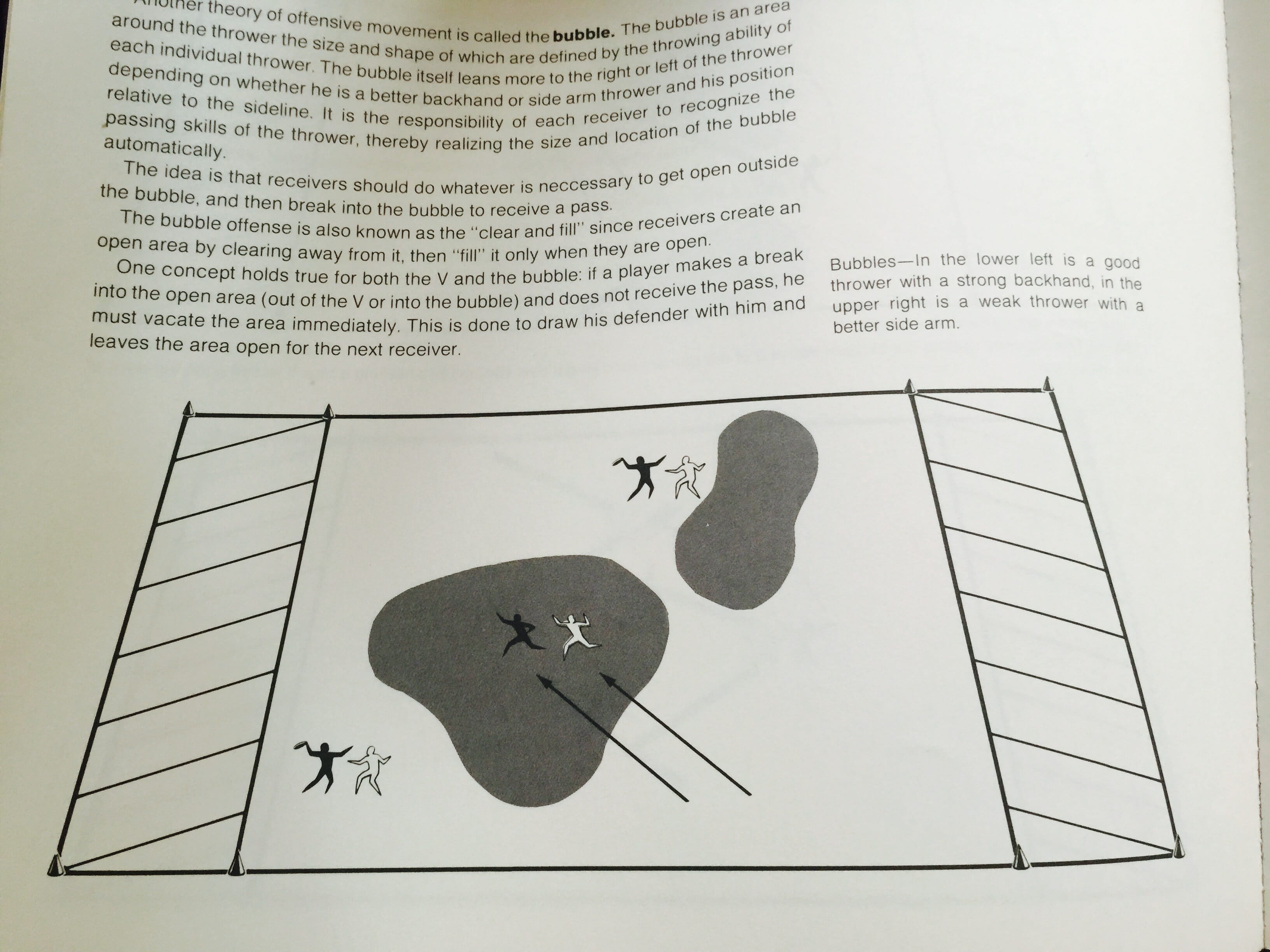

4. It’s not about cutting open side v. break side. It’s about the bubble.

This is another concept I had never heard described, but makes a great deal of intuitive sense. Instead of thinking about cutting into the open side space or the break side space, imagine that each thrower has a “bubble” where they are capable of throwing the disc. Better throwers have bigger bubbles. Your goal as a cutter is to get into that bubble.

We do this intuitively, of course, after developing chemistry with our teammates. You know the thrower has a great break scoober? You cut for it. But this idea of space is one that is worth thinking about — you don’t clear the open space after a cut, you clear out of the bubble.

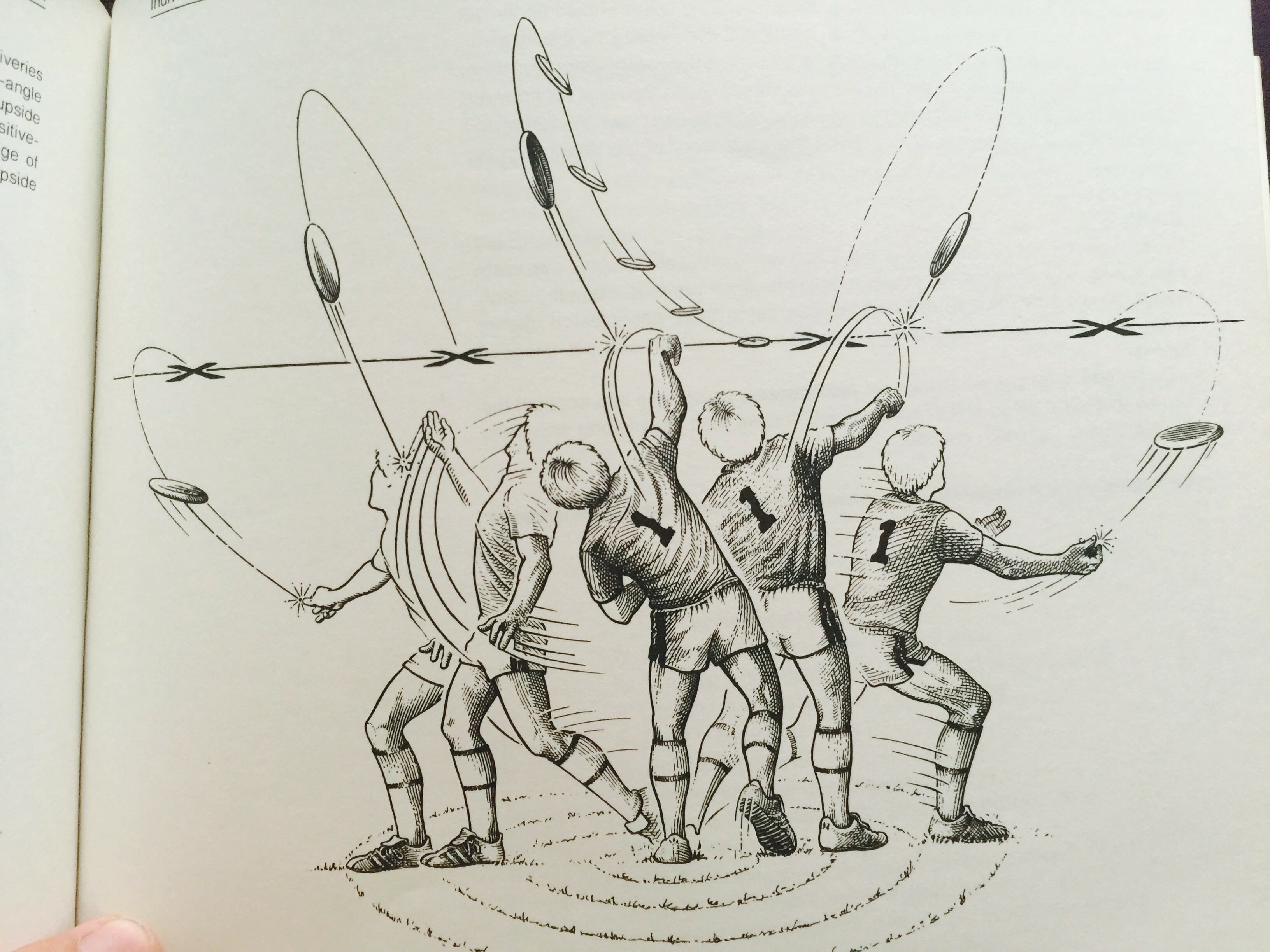

5. Ultimate is awesome because of the versatility of the disc.

This graphic does a lot to describe why ultimate is so great. A ball flies in one trajectory. A disc can go almost anywhere on the field with the right throw.

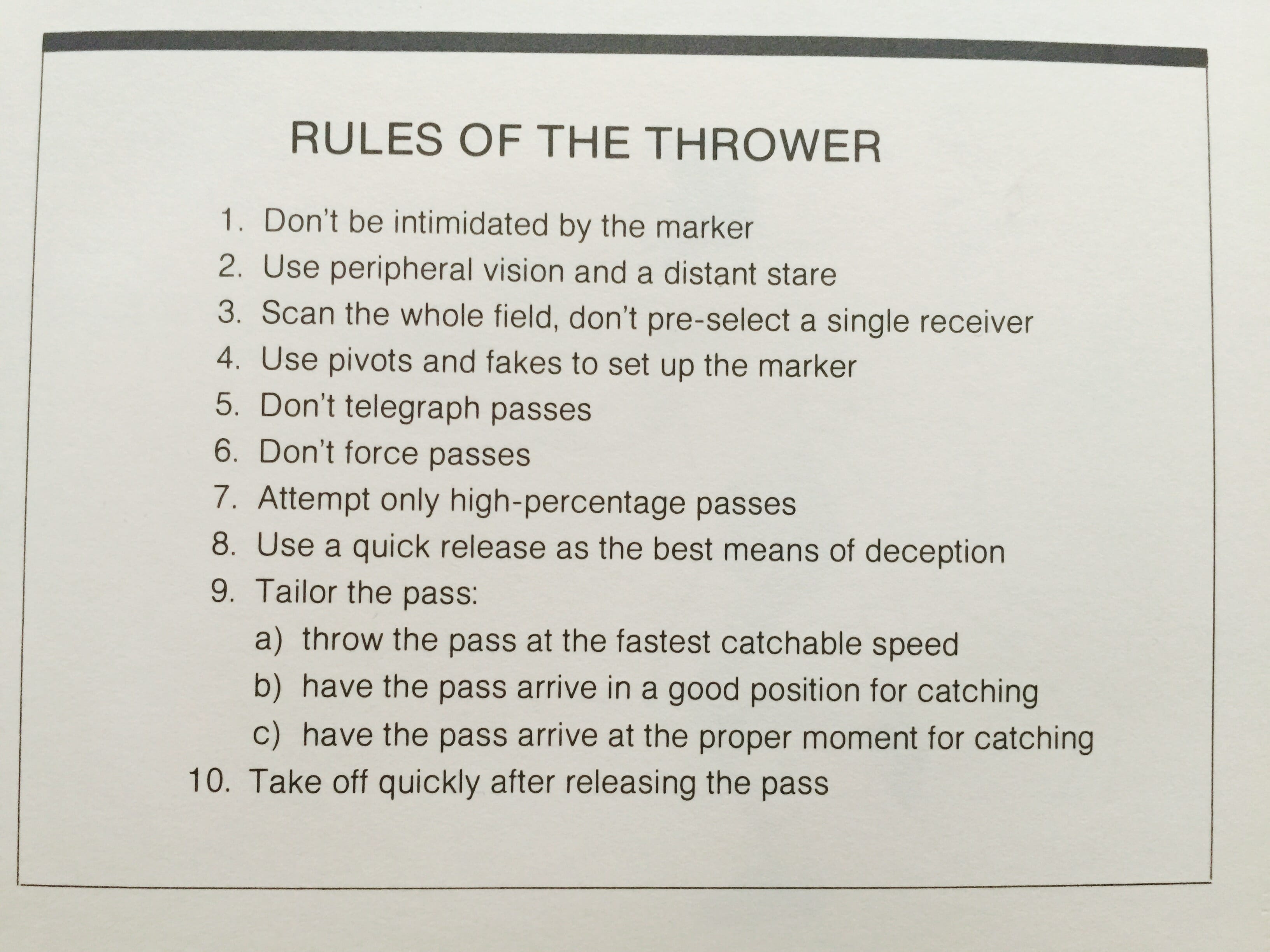

6. These rules for the thrower are pretty spot-on.

You can maybe quibble a bit with one or two items on this list, but these general rules for throwers are ones you could live by. Number 10 is underrated — no player on the field is more dangerous than a handler that cuts immediately after their throw.