The results of a Triangle Ultimate survey on experiences and perceptions of gender equity in ultimate.

September 17, 2019 by Guest Author in Opinion with 0 comments

This article and the research within were submitted to Ultiworld by Lyra Olson and Jack Zhou. Ultiworld editors have made some small changes. All opinions are those of the authors unless otherwise expressed.

Gender equity is at the forefront of our community’s mind. From pickup games to the Premier Ultimate League, women in our sport are speaking out about their experiences in the sport and the many ways, both big and small, that the community fails to include them. Despite the valid complaints of countless women in our community and widespread recognition by many of the inequity that women in our community face, we lacked the data to quantify the extent of the problem. As a result, we could not capture — let alone adequately address — the needs of the women in our community. Furthermore, there are still some within our community that do not believe that these inequities exist or who perceive the complaints to be louder than the problems themselves.

To address these concerns, we developed and distributed a survey to elicit the opinions of the Triangle ultimate community regarding the quality and quantity of playing opportunities, inclusion, and conduct towards women, both on the field and off. We also invited open-ended responses to questions regarding barriers to play, opportunities for community improvement, and personal experiences regarding gender equity or inequity.

Methods

We generated an initial question list with contributions from past and present teammates and friends, which was then programmed on the Qualtrics survey platform. We pretested the survey instrument with 20 ultimate players (90% women) not affiliated with Triangle Ultimate, eliciting feedback for content and clarity of questions.

The revised survey was distributed via the Triangle Ultimate email listserv and Facebook page in March of 2018 with an invitation for both men and women to complete the survey, as well as the Facebook groups and email listservs of several Triangle-area pickup groups. The survey was open to the community for three weeks with periodic reminders sent out.

Survey findings were initially presented to the leadership of the Triangle Ultimate Women’s Committee in late 2018, and more completely to the whole executive committee in early 2019. A full report was then written with input from the Triangle Ultimate Women’s committee. A complete list of the final survey questions can be found on the last two pages of the report.

Limitations

This convenience sample of our local community captured responses from over 150 individuals, of which 117 completed the whole survey. Of those who indicated gender, 82% identified as women. The small sample size of male respondents limits our ability to interpret distinctions by gender within the data, though we do present some of the more divergent patterns in the analysis below. All charts are taken from the full sample data.

Regarding gender itself, this survey incorrectly used the terms for sex and gender interchangeably. This mistake made the survey unwelcoming to non-binary folk, for which we sincerely apologize. The inclusion of “non-binary” as a personal identifier for gender on the final page of the survey does not rectify this error, and we will make every effort for more inclusive language and behavior in the future.

Regarding level of play, 13% of respondents stated that league was the highest level they had played while over 60% of those surveyed competed at the club level. This distribution may skew the data towards the responses of more experienced ultimate players, who, per the data, may have been more shielded from the negative experiences of gender inequity. It is likely that the magnitude of the issue may be underrepresented as a result of this skew.

This survey did not address the equally pressing matter of the racial and socioeconomic inequities that our sport also faces. 84% of survey respondents were white, which may be reflective of our local playing community, but is still not acceptable for the future of the sport.

Results

Summary Of Participants

This survey garnered 157 responses, of which 117 completed the survey. Of those 117 who completed the survey and indicated gender (final page of the survey), 96 self-identified as women. These women had ages ranging from 15-52 years and were 84% white. Years played ranged from 1-28 years, with a mean of 8.6 years of play. The majority of women respondents (65%) have played club, while 13% say league is the highest level they’ve played.

Equality Of Playing Time And Opportunities To Play

Respondents were evenly divided when asked if men and women received equal playing time. However, of those who responded that men and women received unequal amounts of play time, the majority of men thought women received more PT than men, while the majority of women thought women received less PT than men.

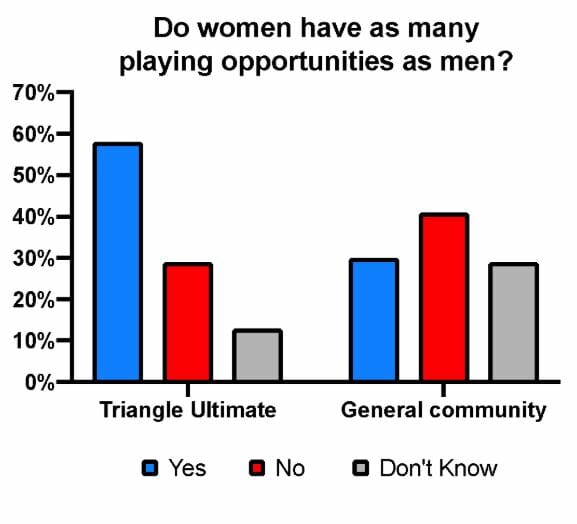

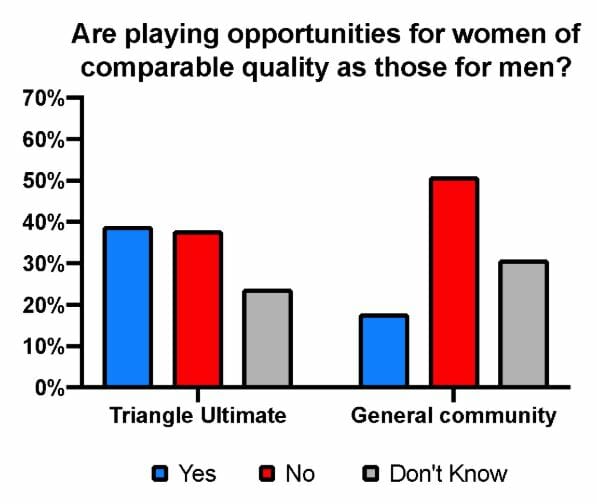

Regarding quantity and quality opportunities to play, respondents were asked for their opinions on these matters as they pertained to the local Triangle Ultimate community as well as their perceptions of the ultimate community more generally. Most women respondents thought that the Triangle compared favorably to the general ultimate community. However, those with fewer years of playing experience were less likely to feel that TU had equal playing opportunities for women than more experienced club players. Men overall and women without club experience were more likely to state “Don’t Know” about the quality of playing experience for women in the general ultimate community.

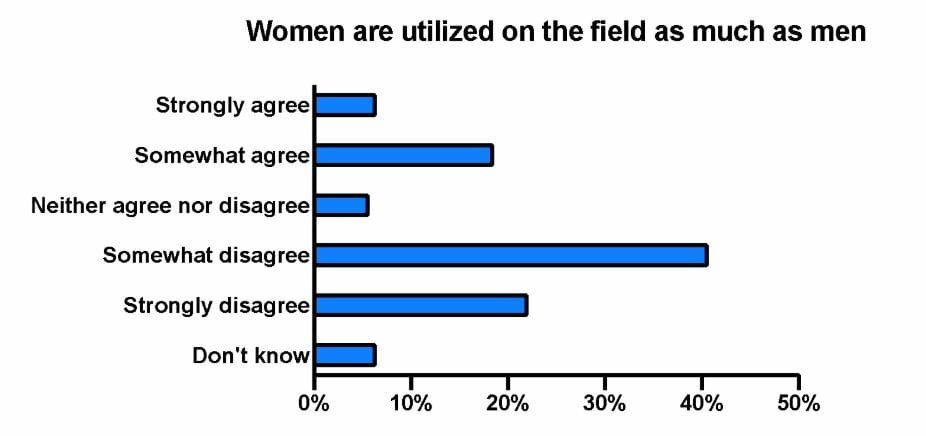

Utilization Of Women During Game Play

We asked if women were utilized as much as men, with examples of player utilization including “being allowed to pick up discs during play, playing their preferred positions, being thrown to, or having their cuts respected.” Overall, the majority of respondents felt that women were not utilized as much as men on the field, in line with some previous research on this topic. This opinion was even stronger among women; while over one-third of male respondents thought that women were utilized equally with men, less than one-quarter of female respondents thought similarly. Individuals with fewer than 4 years of playing experience were least likely to agree that women are equally utilized on field.

The open-ended responses provided rich insight into this perceived unequal utilization, where countless women told stories of feeling underutilized or frankly ignored on the field. Women reported feeling the need to “prove themselves” to be included on the field, and that one error often led to exclusion for the rest of the season. This leads to the perception of a double standard: men are allowed to make mistakes and grow from them while women have to play perfectly to avoid criticism. Below are representative open-ended responses to further illustrate these points (emphasis added by the authors).

“In almost every mixed league I have played in, I often felt I had one chance to prove my worth, and even then every pass I receive could be my last if I make a mistake. If I dropped the first pass of the year, I would never see the disc again. If I ever dropped a pass later in the season, I would not touch the disc again after that singular mistake. If I was playing club, I could somehow rationalize this. However, I have never played club (no interest in the competitive nature of that level) and when I play in a league with random teams I expect it to be FUN, and a place I can learn/improve. Hard to do when you have players who are too intense and then look you off for fear of losing a random summer league game.”

“I remember hearing once, that in ultimate, and probably a lot of sports, when a male player has a turnover or makes a mistake, he is considered to be ‘having a bad day,’ and you’ll hear the sideline say in surprise, ‘he usually doesn’t do that.’ No one will hesitate to keep him on the field or throw to him the next time. However, when a female player makes the same mistake, it’s considered the ‘standard,’ and reflective of her overall talent and capabilities. And that mistake is less redeemable. And when I heard that, I sadly realized how true it was. How I’ve experienced that myself and seen it happen to other women. Women have to prove they’re worth throwing to. Men have to prove they’re not.”

“I think it’s much harder on mixed teams for new women players. My first winter league experience I was told to be a deep every time on zone O and ‘just go deep and stay there.’ I’ve seen new females make great cuts, get open, drop it, and then get looked off for the rest of the season. As I’ve gotten older and more experienced, I’ve been treated better on the field but women still have to prove that they should be handlers or should be thrown to.”

Team Culture, Feedback About Exclusion, And Responsiveness To Feedback

We sought to measure women’s feeling of inclusion on team culture as defined by “feeling welcomed upon arrival to the fields, being invited to team social events, coming up with cheers, or feeling like ‘part of the team’.” The vast majority of women felt included in team culture.

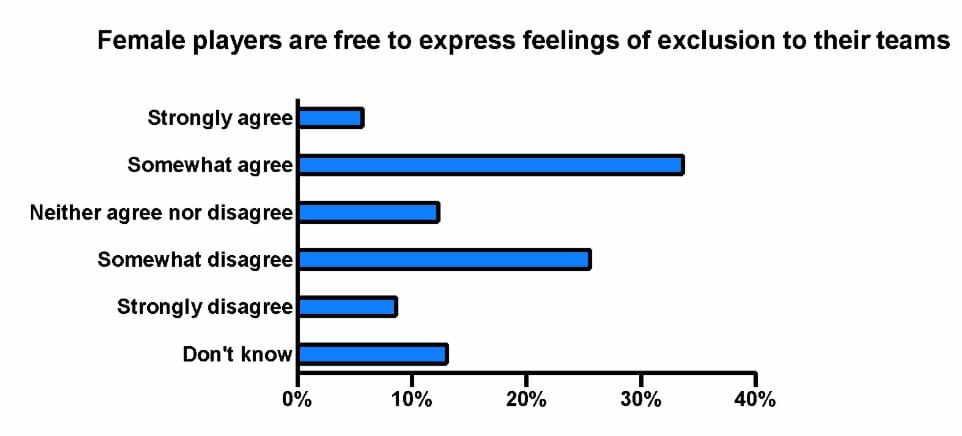

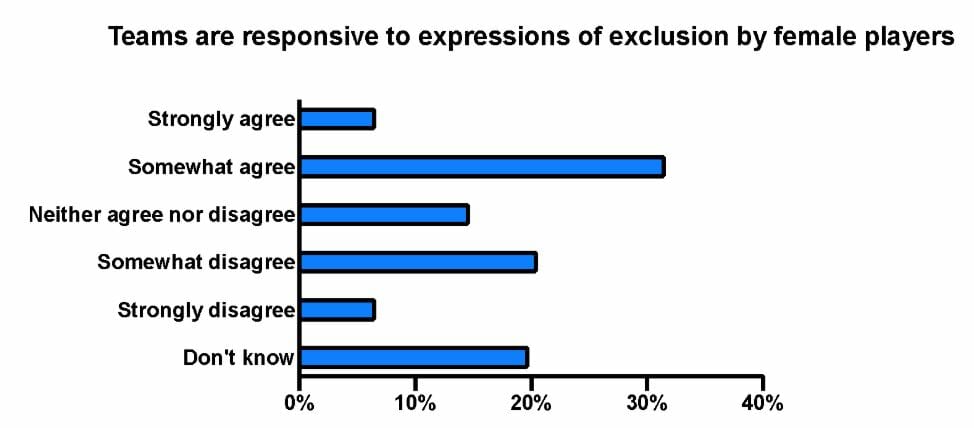

We then sought to measure if women were able to speak up to their teams if they felt they were excluded, and if the teams would be responsive to such feedback. The example in the question stem for this was “alerting male teammates that they have been repeatedly looking off or ignoring their female teammates.”

Overall, women were less likely than men to agree that female players are free to express feelings of exclusion to their teams. In other words, men were more likely to assume that women would bring up issues or feelings of exclusion, while women said they were more likely to keep quiet about issues that arise. Furthermore, when asked if teams would be responsive to women bringing up issues of inclusion, no male respondents disagreed, while female respondents were split over the issue. This points to a divide in perceptions of inclusivity where men tend to believe that women will speak up if women perceive an issue and think they would respond well to an issue if one indeed existed, while women feel wary of speaking up and are unsure if their teams would respond well to such feedback.

As with utilization on field, individuals with fewer than 4 years of playing experience were less likely than groups with more experience to agree that women were free to express feelings of exclusion.

Soft Negative Pressures

Soft Negative Pressures

Beyond playing opportunities and team dynamics, we sought to elicit opinions and stories about the less tangible ways that women are made to feel unwelcome in our sport. We term these collective microaggressions “soft negative pressures.”

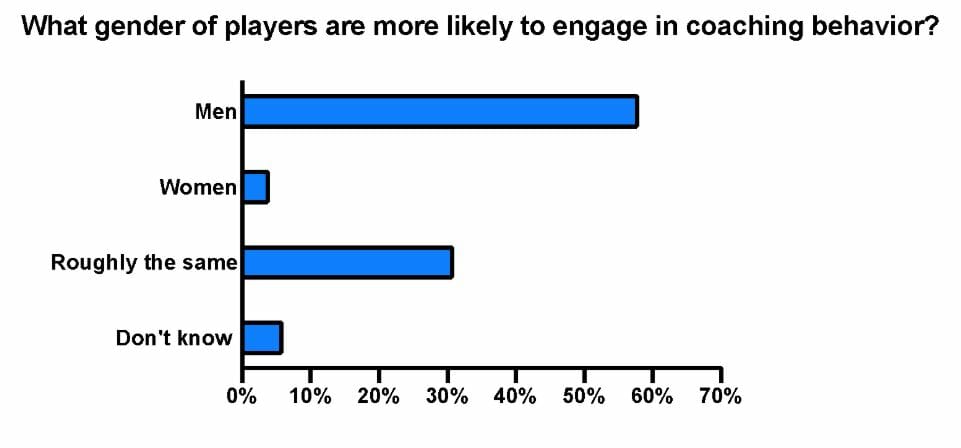

To measure these experiences, we focused on the common gendered slight of receiving unsolicited “coaching” from other ultimate players at pickup and league. The majority of female respondents reported “being coached,” with even higher rates of this behavior reported by those with no club experience. Of respondents who have been on the receiving end of coaching behavior, 2/3 felt that that men are more likely to “coach” than women, with another 1/3 saying that both men and women were equally likely to participate in “coaching behavior.” Less than 5% of respondents felt that women were more likely to engage in “coaching behavior.”

Once again, the open-ended response section provided a depth of frustration that the numbers alone could not capture:

Once again, the open-ended response section provided a depth of frustration that the numbers alone could not capture:

“Many men in the community love to ‘coach’ and tell what you are doing wrong. I have been on a team before where I messed up a play, and knew what I had messed up as soon as I did it. I then had three separate male teammates walk up just to explain what I had done wrong, in spite of the fact that at the time I had been playing for 5 years. Sometimes you don’t need to be corrected verbally, and it is usually men who try to do it.”

“During the first game of summer league, in one of the first few points I played, I had the disc on a sideline and was looking for a dump option. The mark was particularly active, and whatever throw I tried was easily D’ed, resulting in the other team scoring. As I walked off the field after the point, the captain of my team came up to me and started to explain how a dump works. At this point I had been playing for the better part of 6 or so years – I know how a dump works. I just messed up the throw. It happens. But based on what he saw, he assumed that I needed the 101 lesson on dump mechanics.”

“I have had a lot of negative feedback from males when I offer any advice, however they feel the need to tell me what to do all the time. There is an inherent respect for male players and leaders that is not present for female ones regardless of role on the team or ultimate experience.”

The open-ended responses also shed light on some of the other ways that women feel excluded by the community. One frequent complaint was the language used to refer to them on the field. Women persistently reported being called “girl” or “lady” instead of women, or their name. In the words of one community member following a great play for the goal:

“The sidelines at pickup cheered, and the player who threw the assist casually jogged to the end zone and grabbed the disc to pull it, and said ‘nice job, little lady.’ I’m 24, not 6. I wish I could’ve come up with something pointed in the moment to say to alert him to how condescending he was, but instead I just coolly said ‘thanks’ and turned away. It completely soured the whole experience for me.”

Barriers To Play

In one open-ended response question, we asked respondents to describe what they thought stood between them and playing as much ultimate as they wanted. The three most common responses were shared between the sexes: the cost of play, time commitment, and nagging injuries. However, a breakdown by gender revealed some interesting trends.

The overwhelming responses from women were about the intangibles — those “soft negative pressures” introduced above. Woman after woman described having to prove themselves on the field any time they showed up to play, being overlooked constantly, slighted frequently, called by anything other than their name, scoffed at when attempting to mark up on a man instead of the only other woman at pickup for the 15th point in a row, talked down to for the fourth time about why their throw resulted in a turnover, etc. What emerged was a sense of exhaustion from the women in our leagues about their endless battle to prove themselves worthy of inclusion. As one respondent so beautifully surmised, “I’d just rather go for a run.”

Other times, the negative pressures are more explicit. Per one respondent:

“During the TU winter league tournament, women on a team were told not to go in by BOTH men and women simply so the team could win. That makes me beyond furious, because those are exactly the players who won’t come back — those who are trying hard but aren’t the most competitive yet. That’s damaging to someone’s confidence, to the SOTG, and isn’t worth the win they ended up with.”

Women also brought up tangible barriers not expressed by men, such as the cost and struggle to find adequate child care during league games.

For men, the most common response unique to gender was the lack of enough slots in mixed league for everyone to play. They complained, accurately, that not enough women sign up for there to be enough spots for all the men who want to play at mixed league. Several asked why the league has stringent 50% gender ratios (4:3/3:4) if the league can’t support it instead of allowing a 5:2 ratio so that there could be more mixed teams overall with enough space for all the men that want to play. A few went on to question why more women don’t sign up. Overall, it’s a fascinating viewpoint on the impact of inequity.

Discussion

This project leads us to a few key findings:

- Though the quantity of playing opportunities and the share of playtime on the field is decent for women in Triangle Ultimate, women feel underutilized on the field and don’t feel that the quality of their playing opportunities are the same as those available to men.

- Women don’t feel as able to express feelings of exclusion as their male counterparts may assume, and are less likely to report that their teammates would respond well to women speaking up if they did.

- Women report a slew of negative experiences at mixed league and pickup that independently are unpleasant but together make ongoing participation in our community an exhausting experience. Women who are newer to the sport bear the brunt of these experiences and are also least likely to speak up about them.

- Male respondents see a need for more women to join and be retained by the league so that mixed leagues are able to support all the men that want to play.

- Male respondents persistently underestimate the degree of inequity reported by women.

Recommendations

Given These Data, What Can We Do To Make Our Community A More Welcoming And Equitable Space For Women?

On the Triangle Ultimate administrative level, several measures were already in place before this survey. These included a strict 50:50 gender ratio for registrations in Spring, Summer, and Fall mixed leagues, a women’s high school league, GUM programming, and an Outreach committee which seeks to bring ultimate into wider racial and socioeconomic circles than our sport traditionally reaches.

Since this survey, Triangle Ultimate has formed a Women’s committee comprised of interested community members from both league and club level to directly address women’s feelings of exclusion from the league and begin exploration of gender inequity more broadly. TU has updated league captains’ training to equip league leaders to create team environments more open to constructive feedback. They instituted a survey of captains’ performance at the end of each season by their teams, with consequences of removal from future captaincy if they failed to facilitate an equitable environment. They also began weekly “Spirit and Skill” emails to emphasize strategic and sportsmanly aspects of the game that league participants can read and the best league captains utilize in the following week.

Beyond leagues, Triangle Ultimate started a Facebook group for Triangle women as a forum to help one another find child care and talk out frustrating experiences. They also founded a weekend “Women’s Academy” before mixed league, an ongoing series of clinics designed to provide women a learning environment that league alone does not provide. The overall goal of these efforts is to enhance league-wide retention of women through active steps that improve the experiences of each individual participant.

Looking ahead, Triangle Ultimate is in the process of reframing its mission statement to focus on building a community that better represents the Triangle region and its overall demographics. Additionally, TU is crafting an equity statement that details how Triangle Ultimate includes and focuses on equity with its work. More tangibly, TU is considering a transition to a 3:3:1 gender ratio at mixed league, such that three men, three women, and one additional athlete regardless of gender would be able to be on field without question. Though more discussion of this policy is needed, especially with the non-binary individuals of our community, this could be an important step to make the playing environment more welcoming and inclusive.

On The Individual Level

We present a few suggestions for actions each of us can take to improve the experience of our teammates and fellow players on-field and off.

Regarding on-field utilization, women in TU leagues state that they are persistently looked off on open cuts while men in our league state that they will throw to open cuts regardless of gender. This disconnect may be caused by men who generally play with other men being unaccustomed to the timing and spacing of women’s cuts. In general, women require less separation from their defense for their cut to be open. The touch placement of a throw to a smaller window is one that requires a lot of control and consistency, and is a great throw for both men and women in our league to consciously develop. Furthermore, women’s cuts, on average, develop at a slower pace than their male counterparts, so giving an additional stall count for a woman’s cut to develop can enable more smooth offensive flow for a team.

These two points mandate a genuine mental shift for many in the league—one that moves away from considering mixed to be an open game where women have to be present on field for gameplay to occur, to one that actively incorporates women into team strategy. This will require effort from the individuals in the league, but we feel strongly that if you are not willing to make the effort to play a true game of mixed ultimate, then you shouldn’t play mixed.

Off the field, women often receive unsolicited advice or “coaching” about their play from male teammates and, less frequently, female teammates. To be clear, we are not saying that teammates should be silent to each other, or terrified of offering advice or guidance for fear of being thought of as sexist. Instead, recognize that, while most women seek to improve their game, you should ASK a woman if she is open to feedback before you offer it. Often individuals recognize the mistake they made or chose intentionally to make the play they did. Giving feedback without first asking shows your teammate that you do not respect their experience, thought process, or efforts. Similarly, referring to women as “girls” can come off as disrespectful and should be avoided, even if not all women would object.

On the subject of feedback, the data also reveal that women are less likely to speak up about issues on field and off than their male counterparts anticipate. It would be easy for us to suggest for the women in our league to just “lean in and speak up,” but that would ignore the heart of the issue—that women are alternately apprehensive about and exhausted from their efforts to speak up and, based on their prior attempts, don’t anticipate that their teams would be receptive to feedback if they tried. Similarly, the men in our league might occasionally field a critique from a woman on their team, but likely don’t feel the burden of the constant slights against one’s feeling of belonging. Men aren’t aware that speaking up is a hard thing for the women in our league to do and may not realize when men are ignoring the feedback given to them.

As summarized by one respondent:

“There are guys who are very aware of the lack of equity for women. There are also men asking how do we be better. Those are the ones who have to set the tone for other men. Men tend to shake me off when I say someone won’t throw to women; however, when another guy calls them out, they’re listened to. Men have to be partners and fully committed before the culture will change.”

If the men and women on a team intentionally commit to creating a welcoming environment for feedback, the results can be excellent. One league member shared the following story:

“I played a tournament where the men and women caucused at the end of the day to talk about how they felt playing on the mixed team. The women came back and reported how they felt to the men. There was a good amount of ‘joysticking’ happening where the guys were telling women how to pull or were only throwing to them on in cuts. Also, they were complimenting the women after the women did very basic stuff on the field. The women told all of this to the men and instead of complaining, getting defensive, or intellectualizing it, they listened and changed their behavior the next day. It was incredible!”

We believe that the success story above should be the norm in our league. It is within our power to make our community welcoming and fun for all our athletes.

Wrap Up

If the findings of this survey come as a surprise to you, we encourage you to use this report as a jumping-off point to learn more about the experiences of those you play with. We hope that some of you may recognize that inequities exist within our community, even if they aren’t immediately visible to you.

If you find yourself reading this and rolling your eyes, thinking “what of this didn’t we already know,” believe us, we feel it too. The stories told by this data are not new, and your lived experiences and the experiences of your peers do not require validation. Nevertheless, we hope that this collected data will help you or someone in your shoes feel less alone in their experience, and know that there are whole teams of women who have felt similar discomfort and exclusion.

We and TU will continue to use these data, your stories, and your ideas to inform league policies and programming to make our space more welcoming to everyone. We invite you to join us in a lasting effort to create a more equitable community.

Lyra Olson is an athlete and MD/PhD student living in North Carolina. She played undergrad at Princeton, played her last year of eligibility with Duke, and was voted Player of the Year in the Metro East in 2016 and Atlantic Coast in 2017. She plays for the Raleigh Radiance and is a captain of NC Phoenix. Email her at lyra.olson (at) gmail.com.

Jack Zhou is a player in the Triangle Ultimate community whose game tops out at the party tournament level. In his day job, he works as a social scientist for a climate advocacy organization. Find him on Twitter at @mjackzhou.