Who will get voted in his year?

October 13, 2021 by Tony Leonardo in Opinion with 0 comments

While much of the ultimate world was at a standstill over the past couple years, one element of our niche community that kept plugging along unabated is the Hall of Fame. Not only did they induct a class of seven new members in 2020, but they also launched a new website independent of USAU’s and continued their years-long effort to improve the selection process ahead of the 2021 vote.

While much of the ultimate world was at a standstill over the past couple years, one element of our niche community that kept plugging along unabated is the Hall of Fame. Not only did they induct a class of seven new members in 2020, but they also launched a new website independent of USAU’s and continued their years-long effort to improve the selection process ahead of the 2021 vote.

As we await the final results from this year’s election, here’s a look at the 2021 Hall of Fame “Slate of Eight” finalist candidates for Players in each division, as well as those nominated for the Contributor category. It’s worth it to keep in mind that the Hall is currently considering players for whom peak playing years were 2001-2008, although some notable candidates from an earlier era remain on the ballot from previous nominations. We’ll also touch on the Contributor category, which is not limited to those years.

The Hall of Fame has never shied away from exclusivity, even after changes were made in 2017 to open up voting and streamline nominations. The definition of “Hall of Famer” will continue to evolve and this year’s nominations ask voters to rank a wide range of Hall of Fame qualities and intangibles, many of which are only now coming to the forefront. For example, we see our first players — Katey Forth and Ron Kubalanza — with a record of playing semi-professional ultimate listed on the ballot. We have players with defined success internationally. For the first time, we have several players whose careers greatly expanded in the Masters, Grand Masters, and Beach divisions — how much will their success at those levels count? Some nominees feature long careers without signature wins while others have short yet dynamic careers flush with championship titles. Where does a voter rank athletic dominance compared to leadership skills compared to positive examples of spirited play in pressure situations? This year has it all.

2021 will provide difficult choices for voting members, comprised of eligible Hall player and contributor members as well as the vetting committee. A Hall of Fame nominee must receive votes from two-thirds of voters to be inducted. But here’s the catch: a maximum of four nominees in each of the two player categories (Women, Open) can get in each year. Of the list of great players below, a majority will not become inductees — at least not in 2021.

Women

Gwen Ambler

There’s a reason GAmbler is at the top of this list. Ok, it’s alphabetical. But seriously – Gwen will be voted into the Hall on this, her first ballot, because she was a premier athlete with a great mind for the game complemented by a balanced competitive spirit. Her pulls were the Mosquera pulls of the time. Her skill as a tall, rangy hybrid was unique in the game. And the winning – so much winning. What began with Stanford Superfly and a college title in her senior year continued to San Francisco Fury (four titles) and ended with Seattle Riot and a career-defining Worlds 2014 championship. Gwen was a captain at Club Worlds, Country Worlds, and for Team USA at The World Games in 2009, a Kathy Pufahl winner, and a Callahan runner-up. As a defender, Gwen would get blocks in the end zone. As a puller, she would pin offenses back. As a hybrid, she would huck for goals in pressure situations. She was simply a player whose focus, determination, and all-around skillset meant that wherever and whenever she was on the field she was a factor. But even after retiring from playing competitively — with difficulty, as she told Riot she wouldn’t return after 2014 but then unexpectedly returned for the 2015 season that ended with a loss in Club Nationals final — Gwen remained active in the ultimate scene, coaching Riot and serving, at various times, as a USAU Board Member. As an almost assured new addition to the Hall of Fame, we should all be excited to see what she does next.

Chris Cianfrani

There’s a lot of love about the city of Brotherly Love and Chris Cianfrani fits the bill. She was everything Philly and helped define the Philly Peppers, a fixture at Nationals in the 90s (and known for their dancing) for the six years she captained the team before moving to Boston Lady Godiva, where she was again elected captain later in the Boston dynasty. She was known for her calm, cool leadership that never missed a beat. “With Godiva, she would play Nationals as a primary O-line handler and didn’t make any turnovers,” wrote a peer player. “She had executive composure and brought that to both her play and her leadership on UPenn, Philly Peppers, and Godiva. She’s one of the brightest, most team-anchoring candidates on the ballot. The question is whether her make-it-look-easy, consistent, and turnover-free offense will be noticeable and valued enough to earn her the vote. Her cool Roger Federer-style might work against her amongst a group of more flashy and fiery candidates.”

Katey Forth

I first covered Katey and her twin sister Becca playing for the English team Bliss at Paganello in the 00s when Paganello was the best and most competitive tournament in the world outside of UPA Nationals. You couldn’t miss the Forth twins – they crushed it on the pitch and won several titles in the women’s division. Around the same time, the Houston team No Tsu Oh (with Furious George and Condors pickups) dominated Paganello on the open side. Game recognizes game and Katey married No Tsu Oh captain Sean McCall, moved to Houston, and immediately helped start a new team, Zanzara, which later begat Showdown. Katey was always nimble on the field like a ballet dancer, but she closed on a disc like a falcon. Showdown never reached the pinnacle at Club Nationals but I’m not sure that matters for someone who was consistently great for so long — over 20 years across a wide range of teams in Europe and America. The question to me and maybe to the voters is whether some of her early career-defining success with those European teams count. If that’s a yes — then Katey might just find herself in the Hall of Fame.1

Anja Haman

Haman is a rangy lefty with remarkable athletic skills known for baiting (and getting) layout blocks on defenders. She could also rip it deep and do just about anything needed on the field. As Gwen Ambler put it in the 2015 “Predicting the 2025 Hall of Fame” article, when game planning for Team Canada, Team USA had to know where Haman was on the field at all times. Dangerous on both sides of the disc and as a receiver and thrower, Anja was also known for good spirit. She played with Vancouver Goo and Prime with semis and finals appearances but she really shows up on the World stage, earning championships with Team Canada when ultimate debuted in the 2001 World Games in Akita, Japan, and a WUGC Worlds title in Turku, Finland in 2004, among others. In fact, her Hall nomination resume looks peculiar: her first Worlds appearance came in 1991 and her last in 2015 at WCBU in Dubai (a remarkable span of 24 years) while her USAU resume only shows seven club seasons she played.2 In fact, Anja is still playing league today. As such an athletic and spirited force on the field, it feels likely that Haman will join five fellow Northerners in the rare air of belonging to both the Ultimate Canada Hall of Fame and the USAU-affiliated Ultimate Hall of Fame and I’m sure she would be a welcome addition.

Johanna “JoJo” Neumann

Johanna (pronounced yo-Hanna) was an instant phenom, winning the Callahan Award at Tufts her junior year in 2000 and joining Lady Godiva amidst their seemingly ceaseless run to championship glory. A tall lefty with a gravitational pull for discs in her air space and serious distance on hucks who earned a spot starting on the D-line for her monster pulls, Johanna joined an already stacked but dethroned Godiva squad — today’s equivalent of Claire Trop joining Brute Squad. Unfortunately for Johanna, the Godiva dynasty started to fade after a decade of winning and it was Johanna who caught the tail end, merely winning three straight titles on a team where most had won seven and future Hall members like Christine “Teens” Dunlap and Molly Goodwin tallied ten. In 2008 as the alternate Boston team Brute Squad became ascendant, Neumann was out of the ultimate scene and living in Washington DC, working in positive politics. For six seasons plus a season solidifying the 2010 Scandal D-line, she was a force. Will that be enough for the Hall voters?

Liz Penny

I’ll never forget covering College Nationals in 2000 in Boise, Idaho. That was the year the Callahan Rules — the foundation on which our current rules are built upon — and their empowered observers first had a real effect on the game. But on the field, one player that sticks out the most was Liz Penny. Lou Burruss coached Carleton Syzygy and that year he played the field position game: get yardage and punt the disc early and often. DoG pioneered using opposing teams’ starting positions effectively and Lou put it to use as Syzygy marched to the final with a style of play that wasn’t exactly pretty. But that team didn’t succeed without the wild, feral force of Liz Penny on D. It’s easy to punt all you want when Lou knew he had a stopper to get it back. Wherever she was, she made a play. Lots of them, including big bomber hammers that seemed to bring down the sky. Syzygy won Nationals and Penny made a career out of making plays, first with Riot from 2001-2003, then Fury, then Barrio, and finally back to Fury for four straight titles starting in 2009. LP was fierce, and quirky too. You hated to see her line up across from you. Penny didn’t seem to rest, talked (or yelled) to herself and opponents, didn’t really seem to get caught up in emotions or the game —she just went all in and all out. If there’s a lasting memory of Liz Penny, its grass burns on her flank. I don’t know what the Hall will think of LP but it sure would be cool to see here in there causing good, weird trouble.

Shar Stuht

Shar, the longtime leader and captain of San Diego Safari, an absolute fixture at Nationals, was only known to me as a bit of a tough one. Was she mean? Too mean? Did she cross the line? Or was she just mean and tough and focused on success, maybe in the mold of Nancy Leahy Glass, the Nemesis founder now in the HoF? That question is for her peers to answer, and no one I’ve spoken with puts her in the blacklist category for spirit under pressure. Her longevity and success in the game is unquestioned: 21 straight seasons with Safari, most of those at Nationals and mostly as captain. Was she the best player on the field or just had the best throws? Is there a path to the Hall of Fame for guiding an elite team for more than two decades yet never making the semifinals?

A former teammate describes Stuht as a, “fiery handler who may still have the best hammer in the history of the women’s division. She could deliver the disc anywhere on the field, which rendered many zone and matchup defenses useless. Teams would often play a ‘box & one’ in an attempt to contain her distribution of the disc. Safari under her rule had the potential to upset any team at Nationals if the wind was right. But the question is real as to whether her toughness was in a way that motivated players or in a way that was too hard for some to handle. The answer is both. Outside of her achievements as a player, she has dedicated her life to mentoring players and has groomed several sure-to-be first-ballot HoF players coming up through the ranks.”

Vida Towne

This is Vida’s second round as a finalist, after coming up short in 2020 voting. Vida and her sister Leah — among others, Kathy Scott comes to mind — drove the athleticism of Seattle’s Women on the Verge to the next level. At the time Boston Godiva was athletic but controlled and regimented in their roles. Verge was flying all around the field and Vida’s tireless defense and speed led to big layout blocks that her team would rally behind — usually to victory. There were Seattle women’s teams before Verge but it really was Verge who took Seattle ultimate to the next level, winning two Club Worlds championships in the late 1990s. But Verge never won Nationals despite the abundant talent and so Vida, considered the heart of elite Seattle women, helped co-found a new team, Seattle Riot, that did finally bag the big one in 2004 marking the end of her career. Vida has the distinction of winning the first-ever Kathy Pufahl award that year for her good spirit and good play. But was she enough of a game-changer for the HoF in a career that lasted only eight seasons of Regionals and above competition? That’s for the voters to decide.

Open

David Boardman

Dave arrives at this Hall vote, at first glance, as a game-changing cutter who could roof anyone in the game for Chicago Z and Minneapolis Sub Zero from 1996 to 2006. But that alone probably wouldn’t be enough to garner a nomination, even if Dave Boardman was one of the best for all ten of those years. There weren’t a lot of semifinals to be had in the Midwest at that time which is understandable, but where Dave Boardman did find hardware to bring back to Minneapolis was in the Masters division. In 2007 he joined the new squad sponsored by the local ultimate-player-owned brewery, Surly. During the next seven years, they won five times including four in a row and that’s when Surly redefined the Masters division. You can look it up – Masters teams were all about getting the gang back together for one last-ditch shot at glory or one more legacy-building title. But Surly was different. Surly came back every year with a core group of guys and hungry new recruits. They returned to Nationals as a regular unit of guys who played, trained, and crushed it as Masters players, not Open players moonlighting in an age-delineated division. Before Surly, there were 14 different champions from 10 different cities in 17 years of Masters. Surly changed that and became the first team to think of Masters like how we think of Club — and some of that credit undoubtedly goes to Dave Boardman.

Mike Caldwell

Gotta live spiky Mike Caldwell and his longevity as the heart and soul of Seattle Sockeye. There were a lot of great Sockeye players over the decades of Mike’s commitment to the team and, for me at least, it was hard to distinguish Caldwell from the name-brand athletes like Alex Nord, Chase Sparling-Beckley, Lou Burruss, Ben Wiggins, and Sammy C-K, just to name some of the title winners from the mid-2000s. So why is Mike on this nomination list before them? First, he was a defensive stalwart. Second, he never stopped playing Sockeye, at least not until he was in his late 30s. Three, he just coached 2019 Sockeye to their first title win since 2007, and Four: he played at the highest level of Open Club ultimate for 20 straight years. Try it sometime — you probably won’t succeed. It’s an honor to be nominated so soon after retiring from play. For me, at least, this nomination is a reflection of the greatness of the Sockeye program over the past 25 years and Mike’s indisputable role as the defining player at the core of the program.

Alex de Frondeville

Alex de Frondeville — or the Count, as he was known — had a devastating backhand huck, a deep hammer from the forehand side, and vicious blades to keep opponents guessing. Although seemingly slow and a liability on D (but remember DoG perfected not turning over the disc), de Frondeville had a quick first step and could always get open on a reset, and often with power position. At the height of his game—which he extended for more than decade by winning a slew of titles in Beach, Masters, Grandmasters, and GGM with longtime O-line buddy Jim Parinella — de Frondeville was the most dangerous thrower in ultimate on par or greater than someone like Ashlin Joye or Jeff Cruickshank. Without de Frondeville, DoG doesn’t win six championships — they don’t even win half that, even if DoG D-leader Jeff Brown was a secret genius behind their success. On these qualities with a six-time champion like DoG alone, I would consider de Frondeville a Hall of Fame lock.

At this point, most of the DoG greats are enshrined in the Hall (with a few notable exceptions)3 and Al isn’t one of them. Parinella was called into the Hall seven years ago, so what’s been the hold-up for a player like de Frondeville who was absolutely invaluable to his team? Well, this again comes down to attitude. de Frondeville was always brash, fiery, “number 1” (his number), and he wore his egoism proudly with those famous dEath or GlOry shirts. While he and his teammates might have seen his demeanor as just an insanely competitive streak, others think he was a downright jerk on the field. Voters know this, and it’s at least partially why Al is still not in — and is now on the ballot for his last chance.

Let’s dig deeper on this one: the Hall nominees are voted on by peers. That means aging Hall members won’t vote, limiting the number of voters down to between 40 and 44. Al is going to need two thirds, which will be 26-30 votes. But a curious thing happened this year: Jon Gewirtz — considered the best defender of his generation — does not appear on the Slate of Eight for the first time in four years, which effectively means that he has been denied entrance to the Hall because of his Spirit-of-the-Game transgressions.4 But Gewirtz’s teammates on NYNY are in the Hall, they will vote, and they are legion. Would they support rival de Frondeville, who also hasn’t found enough votes the past three years and doesn’t have the cleanest reputation for Spirit, mirroring Gewirtz’s un-envious position? It’s been clear for about a decade that the Hall of Fame takes questions of character into mind for voting, even if several of the brashest and most transgressive players of the sport are already in. Will de Frondeville be one of them? Or will he be left out?

John Hassell

When Gwen, Kyle, and I compiled names for future Hall of Fame nominations leading up to 2025 and cross-referenced them across the geography of time and space in North America, we inevitably missed a few. Notably, I remember missing West Coast 80s players Rick Gallagher and Bob Sick who made the Hall a short time later, as well as Pat “Bagger” Lee, the Southern celebrity. But the readers immediately went somewhere else in the comments section: John Hassell. The story on Hassell from my perspective was simple: he was The Man on the East Coast, the dominant force that brought Toronto GOAT to life. Prior to his heyday, elite Canadian talent would migrate West to Vancouver to win titles. Andrew Lugsdin, the Easterner, is a great example. But Hassell stayed in the East and therefore he didn’t win Nationals – or even Regionals — though he did help turn GOAT into a Nationals fixture while he himself was a fixture for Team Canada, competing in two iterations of the World Games, three for WUCC and WUGC, and two more in the Masters division from 2004 to 2017, all of them semis or above finishes. Will it be enough?

Augie Kreivenas

I love seeing Augie’s name here. When I first started covering Nationals in the late 90s, one of the most interesting teams to cover was Ring of Fire. They were fast, athletic, together as a team, and they were underdogs. And lanky, oddly-named Augie Kreivenas was one of the captains. Elite teams were insular then, as some are now, but Augie was seemingly always gentle, always available, and he carried himself like the leader he was. Fair-minded, great at ultimate, and a tactical leader for Ring of Fire for a long, long time. As a player, Augie was in the mold of Steve Mooney: a long, confident, hybrid handler capable of doing anything you could do, but better. Once in the Masters division, we matched up on each other. It had been a decade since I had seen him and I wasn’t sure if he knew who I was. The game was close throughout and we were the underdogs this time and the game was down to the wire late. During a hard-fought point, I knew I had to make a play and I got a bit of separation in the end zone on a short throw, I leapt up, and got one over Augie at a critical juncture in the game. Perhaps it was an embarrassment to him, I don’t know, but he didn’t react that way. Like the person he is, he stayed focused, congratulated me without smiling but without anger, and went back down the other end of the field for the next point which they scored on O. His team that year was Boneyard and they won that game and made it to the final — a precursor of great things to come. My impression of Augie is that he was always a true gentleman and if you wanted a teammate to lead you into battle at the front of the brigade, he was your man.

Ron Kubalanza

Free Agent: The Legend of Ron Kubalanza isn’t a film you’ve heard of yet, but it will be if Koobs makes the Hall. And there’s good reason to believe he will. Unlike most players in our half-century of history, Ron made it a point to play on every great team that wanted him — or that he wanted to join in his quest for hardware. He was a combination of Brett Matzuka and Goose Helton before Brett and Goose took the field. Ron found a home on teams in San Francisco, Chicago, Seattle, Minneapolis, Vancouver, Boston – didn’t matter where – because he was a sick athlete with massively long limbs and crazy hops who carried a bag chock-full of big-game confidence to make whatever play was necessary. Full-field huck? Check. Sky the pack? Check. Blaze a 40-yard under against the opposing team’s fastest defender? Consider it done. Even so, the “Curse of Kubalanza” was the storyline for years as elite teams he joined would somehow falter with his presence as a pioneering free agent. In fact, his only Open Club title came with Sockeye 2007. Notwithstanding, from 2002 to 2009 Kubalanza was on everyone’s universe-point line. He was Mister Make-a-Play and your hypothetical universe point would absolutely have him on it. Controversially, he wasn’t on the 2005 World Games roster but came to Germany and practiced with the team as the alternate anyway. If the next team Ron joins is the Hall of Fame, it shouldn’t come as a surprise.

Fortunat Mueller

Fort was a game-changer. Not tall, not fast, not big, not flashy — but Fort on the field was improbably all of these things. Okay, maybe Fort was deceptively fast, maybe he had Dylan Freechild-like quickness, maybe he had forehand hucks like Jimmy Mickle, impeccable timing and field awareness like Johnny Bansfield, and big-moment playmaking ability like Joel Schlachet. All of that is true but you would never guess it from his reserved, “Swiss” demeanor. Nurtured at Scarsdale High School in the New York City suburb of Westchester (by coach Jon Gewirtz), few might have believed how quickly Mueller became the force he was. 2019 Brownian Motion succeeded in rebuilding the program by focusing on the field and being serious about ultimate — just as it happened 20 years earlier with Fort (alongside Justin Safdie and others) at Brown. And the success came just as fast, going from Regionals afterthoughts to National champion in short order. Oddly, Fort’s success came in reverse order after he won the Callahan as a senior in 1999. That summer, he and a pack of the Brown core were recruited to join the five-time champion Death or Glory for Club Worlds. He did, and they won. Later that fall he won Club Nationals with DoG — their sixth straight — and it felt like the team wouldn’t have won without him. And finally the following spring he won College Nationals as a fifth-year — the triple peak in reverse order in 10 months’ time. Fort was part of the inaugural 2001 World Games with Team USA and played another 10 club seasons with DoG and Ironside but never found the success and dominance he experienced from 1999 to 2001. But the players who played with and against Fort will know his game during this later period of time and whether or not it remained at elevated levels that may determine his place in the Hall.

Mike Namkung

It’s interesting that Mike’s name comes up before fellow UCSB Black Tide alum James Studarus,5 a linchpin of the Black Tide and Condors dynasties of the late 90s and early 00s, but Namkung may be here on the nomination list as one of the greatest “glue guys” of his era and a uniquely gifted all-around player. Mike had tremendous ups and seemed to levitate when skying for a disc before landing in position to quickly throw the next pass. His skills were augmented by his early adoption of the functional movement workout regiment; training allowed Mike to remain a force for more than fifteen years of elite competition. After titles with Black Tide and Condors, Mike pulled in another with San Francisco JAM and added a WUGC championship and a World Games win for Team USA as a co-captain. Ultimate has never been a hero-ball sport and players like Mike Namkung epitomize the collective nature of success: Mike was the everyman’s player with a big heart, great spirit, tremendous love for the game, and a genuine resolve to help others. He traveled to Colombia as an internationally recognizable star of the Condors in the early 00s to help teach the sport to a new generation of players. There’s a strong West Coast contingent in the Hall of Fame and a slew of his peers, many of whom he played with during his nomadic travels (I can count myself among them, even if it was just for one summer tournament), and I suspect there will be serious consideration for Mike’s induction.

Contributor

The Contributor category is about five years behind the Player category with a backlog of names who should be considered for nomination. Like the Player category, initial voting on the Contributor category was done by a peer pool group up until last year, when it vanished. Currently, there is no voting for this category, which means the 2021 nominations were selected by a Hall committee. The Contributor category is scheduled to undergo a reorganization soon, much like the Player category did several years ago. Right now there are only 12 Contributors in the Hall of Fame covering 52+ years of ultimate and only nine of them vote. It’s not a great situation, unfortunately.

But this year’s selections may have produced a better result than the peer pool nomination process that cobbled together a mish-mash of coaches, administrators, writers, tournament directors, and photographers across a multitude of decades where they may or may not have interacted with the people they were voting on. Expect changes in 2022, but in the meantime let’s enjoy some smart nominations that the Hall has put forward for 2021, from a dominant coach to two “Look Back” contributors who made meaningful impacts on the sport in the game’s earlier years.

Jennifer “JD” Donnelly

I loved covering JD and learning about coaching. A lot of style, brash determination, loads of brainpower, easy yet sharp humor, and a killer knack for knowing how to win by recruiting, maximizing, and motivating your talent. JD told me about the Laws of the Jungle and the Inner Game of Tennis. JD was probably a tough coach – I don’t think she suffered losing well – but she really did get the bestout of her players. Two of them won the Callahan under her tutelage — Andrea “AJ” Johnson and Dom Fontenette. Donnelly coached Stanford Superfly to three straight national championships and a 106-game winning streak, won three Club titles as a player, and helped co-found Fury in 1997 when Fury was almost like a Stanford Superfly alumni squad. Here’s what one player says of coach Donnelly: “JD was the best coach I’ve ever experienced in my career. She was able to foster confidence, develop talent and strategy around players, and make in-game adjustments better than any other coaches.” Early in the 00s, JD hung up the cleats and clipboard. When she first started coaching there were very few college coaches, but when she left it was considered a must for any serious college program. I’ll never forget the excellence she brought to the game and the principles of intensity, visualization, and skill that Stanford Superfly and San Francisco Fury exhibit to this day. If those cross-generational, team-defining principles can be even partially credited to JD, then I think she’s gonna make a wonderful addition to the Hall of Fame.

Mary Louise “Louie” Mahoney Cohn

“Louie” was one of the driving forces behind the introduction of the Women’s Division of ultimate. As most women did in the early days, Louie began playing ultimate with men. She loved frisbees and all forms of disc games but, being a talented field sport athlete, she was mostly drawn to ultimate. Boston was an early hotbed of ultimate activity and Louie was a founding mother of the long tradition of successful Boston women’s teams, starting with Boston Ladies Ultimate (BLU). Before there were critical numbers of women playing, she recruited and taught many of the early women’s players while advocating for a separate women’s division. Louie was one of the top female athletes on the field playing in the first Women’s division at Club Nationals in 1981 and a huge part of BLU’s championship title that year. Women’s Ultimate wouldn’t be what it is today without Louie’s early years of planting the seeds and showing those to follow the potential in the sport and in themselves.

Frank Revi

Revi was the long‐time UPA College Director from 1986 to 1994. While Mike Farnham kicked off the formalization of the College Division as its first college director, it was Frank who fully figured out what colleges required in order to treat ultimate as a full “Club Sport,” including requiring teams to have a roster composed solely of athletes formally registered with the college and also meet reasonable limitations on playing eligibility. Quite frankly, the decision to do away with non-student ringers was initially quite unpopular, and the administration of the roster collection was a real grind, especially in the early days, but Frank managed it all in good spirit and with quiet efficiency. Frank had the staying power to sort out and nurture the College division to become the largest division in the UPA, and it remains so with USAU today. Frank began playing ultimate in high school in the late 1970s, captained his MIT teams to College Nationals in 1985 and 1986, and played with Windy City in the late 1990s, playing in three Nationals and at the first World Ultimate Club Championship in 1989, before moving to the West Coast and finishing his competitive career in the late 1990s.

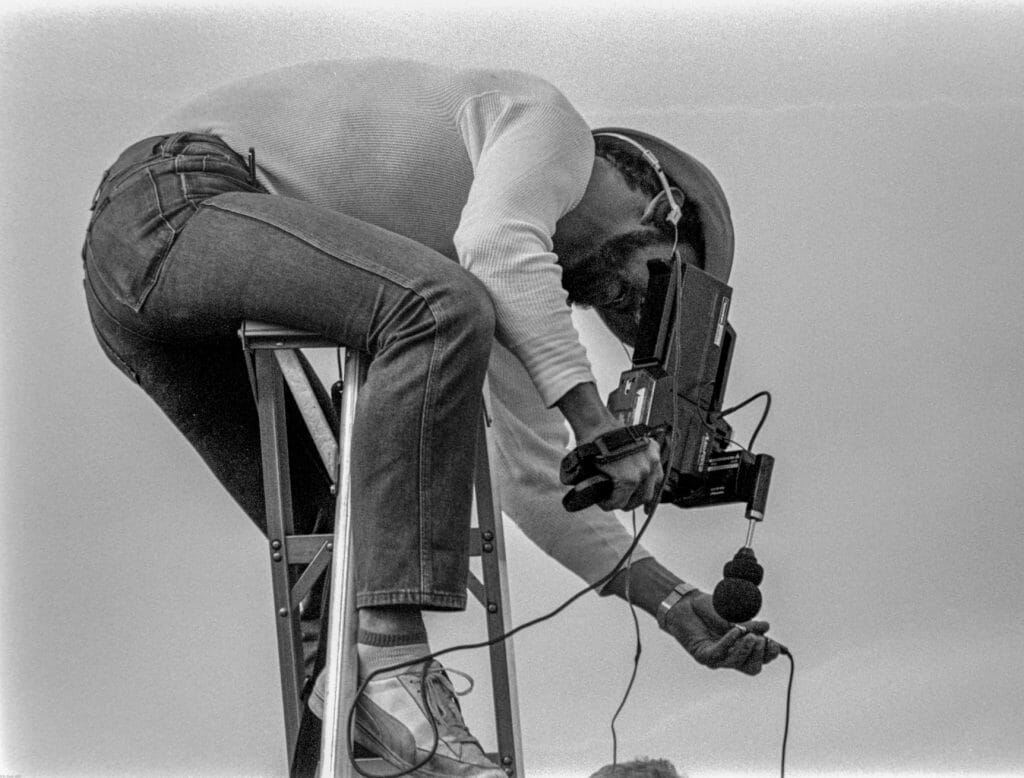

Special Merit: Early Photographers and Videographers

It’s a genius stroke by the Hall of Fame committee to use the Special Merit category to recognize our sports’ mostly forgotten media members of the 80s and 90s and induct them en masse to the Hall of Fame. It’s been too long, but better late than never and truth be told, there’s a reason a lot of these early visual artists were left behind: photos and game footage from the 70s, 80s, and 90s are in a stack of boxes at USAU headquarters and have only recently been indexed. Most of the archives haven’t been digitized yet, which means that with the exception of Joe Seidler’s comprehensive history book series Ultimate: The First Five Decades you probably haven’t seen much work from these pioneers — until recently.

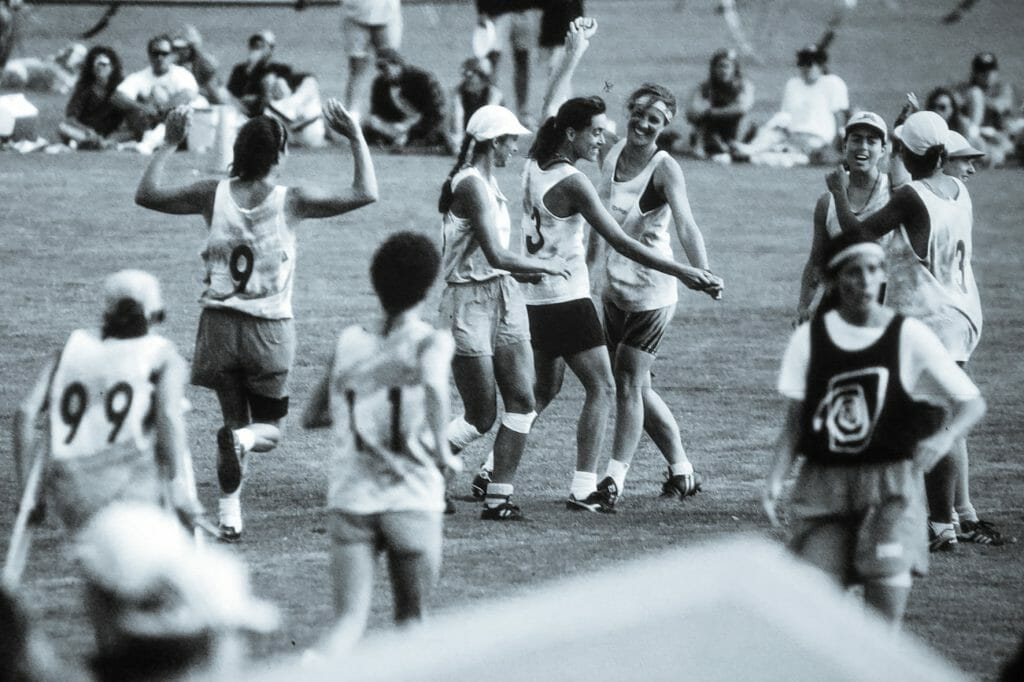

In December 2020, Karl Cook appeared on Shanye Crawford’s Disc/Diversity livestream featuring Black ultimate players who spent time in ultimate media. In turn, perhaps in conjunction with a holiday gift of a new photo scanner, Karl began to digitize his film negatives and post them to the Ultimate Alumni Facebook page. It turned out that Karl had taken hundreds of fantastic photographs from some of our sport’s earliest tournaments. The first women’s National Championships, for example, including the game’s final goal caught by Rhonda Williams, one of ultimate’s early Black pioneers, are part of Karl’s mesmerizing collection.

Positive comments flooded in for Karl’s photo posts, old frisbee heads reappeared after they found themselves identified, and it slowly became clear that these photos were Hall of Fame stuff.

Karl needed to be in the Hall but when the Hall scratched beneath the surface a vision began to take shape to include more of our deserving early pioneers of the visual medium. It’s a good move by the Hall to use this category and in the future we can expect to see the Special Merit category used to induct other groups — like well-established tournaments and their tournament directors, for example. In the meantime, it’s a delight to share the works of these pioneers with a new generation of players and maybe we can see more of their works in the future at UltiArchives.

Rick Collins

Rick and I shared rooms together for UPA Club Nationals as the sole writer-photographer team in the 00s. Almost the entirety of media for some time was one official writer and one photographer covering 48 teams. Things I’ll always remember about Rick are plenty – 1) he was a good player 2) He was salty, and I loved that. He wasn’t the only guy with a big lens that would scuffle with you if you got in his way for a shot that I’ve worked with over the years, but he was one of the better ones at getting the shot 3) He took great photos 4) He’s Canadian. Like others on this list, Rick has a dozen marquee photos that are worth the price of Hall admission alone. Rick’s style was a beautiful mix of impeccable framing, timing and focus. Rick was insatiable, going after shots and getting to the spot on an overcrowded sideline when finals were played at the Sarasota Polo Fields on a crisp Sunday morning. He lived for the action, thrived on big moments and never shied away from emotion.

Karl Cook

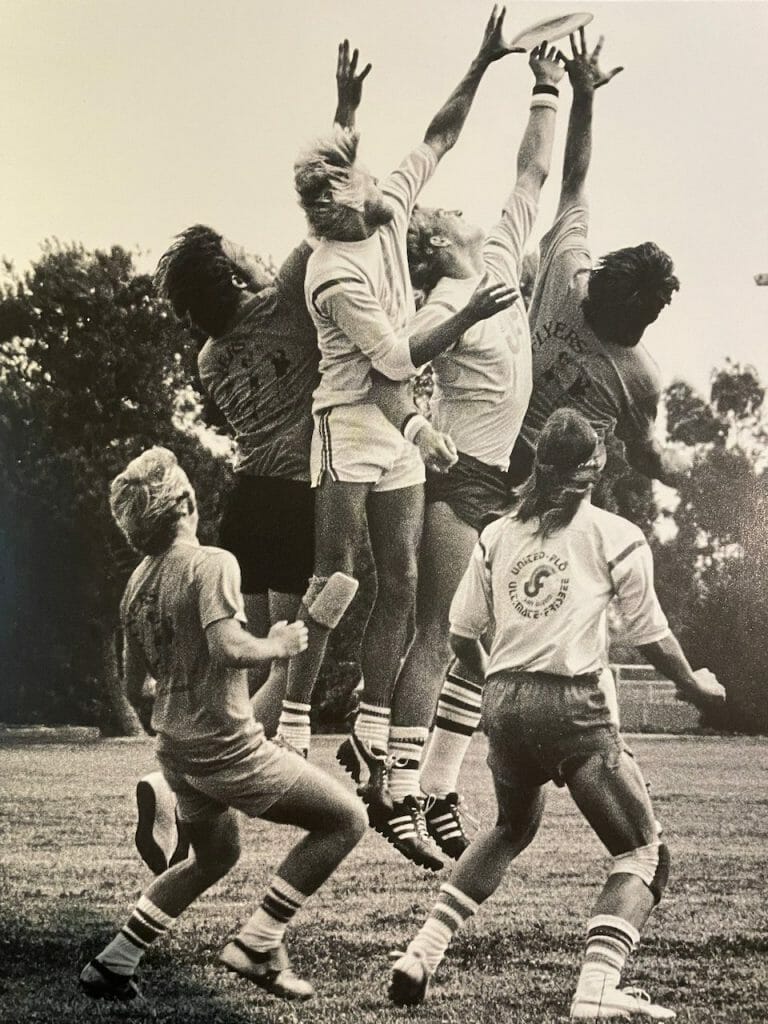

Karl Cook may be the most beloved photographer of them all. You couldn’t find a better spirited, friendlier, and more helpful demeanor in all of ultimate than Karl. But let’s not mince words — Karl is an absolutely fantastic photographer and one of the photographers that we featured prominently when creating The First Four Decades. Adam Zagoria and I worked with Dan Revelle to source most of the material for the book. For my first chapter starting in 1988, Dan started to uncover unbelievable photos without accreditation. Usually, it would turn up to be the work of Karl or Dan Hyslop. But we only got a small fraction of what Karl shot because, as it turned out, the UPA only developed a few photographs before returning the negatives. In going through Karl’s work recently, you will find his style immensely rewarding. Karl captured full-body shots — he never “cut off feet” of the players with his framing. So a classic Karl Cook photo will often reveal just how much air some of these ultimate players were getting when they leaped to make a catch. He also was an expert at capturing action — never easy — with a nose for where to get the shot and when the disc would be in the air. The iconic Pat King spike, now seen in GoodBoys clothing, is a Karl Cook shot. But there are more — lots more. Do yourself a favor and check him out on the Alumni page. You won’t be disappointed.

Dan Hyslop

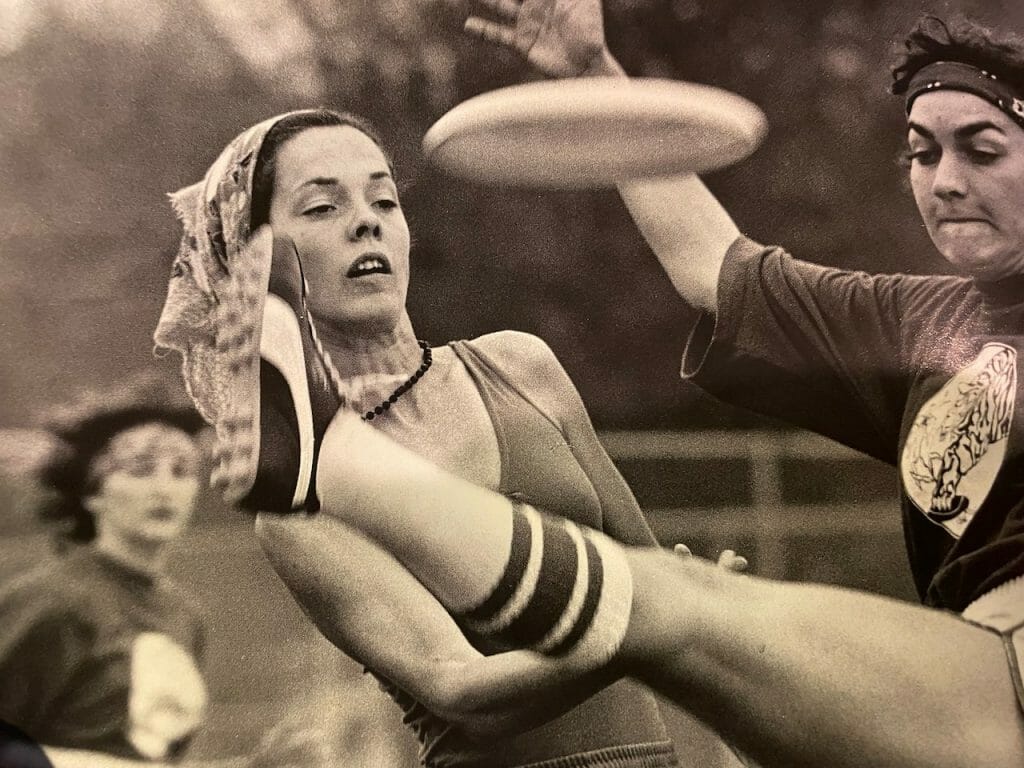

Dan is another of the greats whose contributions to the The First Four Decades were invaluable. He captured Nationals in the 90s with a focus on the intensity of players. His photographs opened up the color spectrum more than others, a bright and vivid palette that mirrored the times. There are dozens of iconic Hyslop shots that will forever be a part of ultimate history, many capturing the NYNY, Maine-iacs, and Lady Godiva dynasties in their full fervor. So many great photos are the work of Dan Hyslop, please check on the alumni page for more awesomeness.

Scobel Wiggins

Scobel was the first Sideline Parent that I knew in ultimate to become equally or more famous than her two quite-famous sons, Ben and Seth Wiggins. Scobel became a single-name celebrity and she opened up a slice of the scene we hadn’t seen much before in the Pacific Northwest. Rick Collins was up near Vancouver around the same time but you have to understand that the action in the NorthWest was off the charts throughout the 00s and Scobel was there to capture it. This statistic may be difficult to comprehend, but a team from the NW Region (which included Northern California up until 2010) won Nationals in Mixed eight straight years, seven straight in Open, and ten straight in Women starting around 2002, depending on the division. Furthermore, many of those teams defeated other NW teams in the finals and/or semis. In 2004 and 2005 the NW placed three Open teams in semifinals. All of this elite action and we still had tournaments like Spring Reign, Potlatch (now Sunbreak) and Solstice that collectively define what it means to be an ultimate player and Corvallis, Oregon native Scobel was there to capture it. She was iconic with a hat and monster zoom lens, and her style was unique too — she revealed the intensity of the action better than anyone in close-up and extreme close-up shots, flattened but unmistakable. You can tell a Scobel shot when you see the expressive faces of ultimate, the grasping hands, twisting bodies, discs just in or out of hands and grass. And her team shots were always jovial, ridiculous, bursting with action. Scobel brought to life the little moments of ultimate that we all share but rarely see. Her style wasn’t seeking the epic highs and lows of glory and failure but rather the singular striving of a player seeking to connect.

Stu Beringer & Chris Perry

Both Stu Beringer and Chris Perry were some of the early professional photographers to capture ultimate and define its imagery.

Perry is best known for his iconic, award-winning 1981 shot of two California teams, San Diego Flo and Orange Sky Flyers, vying for the disc in a pack.

Stu captured Nationals from 1980 to 1985 and has some famous shots of his own including this one from the first Women’s Nationals in 1981 between Ultimate Synergy and Wild and Ready.

Lee Flynn & J.R. Reynolds

Lee Flynn was the Akshat Rajan and Rob Baril of his time, videotaping countless tournaments, mostly with VHS camcorders and producing them with broadcast commentary. J.R. Reynolds was a videographer in the Southeast, perched on a ladder or stepstool at the big tournaments and filming, also on VHS. He was unmistakable with an eye patch and brimmed hat like a character from a modern-day Western. Both men were ubiquitous and their spot in the Hall is deserving.

If you look at Katey Forth and Ron Kubalanza’s resumes you’ll see several years playing semi-professional ultimate, Katey first with the touring Eurostars then with Austin Torch of the PUL, Ron with the AUDL Chicago Wildfire. This is a pleasant surprise; I had guessed that with the disagreements between USAU and the semipro leagues that the Hall of Fame would simply choose to ignore the semipro leagues and they would create their own Halls. But instead, the Ultimate Hall of Fame — independent of USAU but tightly liaisoned — made a smart move by including semi-professional league statistics, allowing the players to prioritize where playing means the most to them. Look for this trend to continue in future nominations. A question left unanswered is how much of an effect semi-professional success will have on a candidate’s nomination. ↩

She did play more, but USAU only recognizes USAU-sponsored Regionals and above. ↩

Chris Corcoran. It’s hard for me to see this list and not see some of the greatest players I’ve ever covered on here. But our sport is a weird one for a lot of reasons. We don’t have great stats from the 80s and 90s (this is only partially true, we have very detailed RUFUS stats for many semis and above over a ten-year period of time) and we have this little thing intertwined with our athletic pursuits called Spirit of the Game. And that’s where this list comes in — did Cork (and below, Studarus) cross the line? Cork was insane in the air — he looked (and acted, at times) like Animal from the Muppets. His vertical was spectacular, like Jeff Babbitt or Terrence Mitchell inhabiting the body of Paul Arters; He could roof anyone in the game and you’d never suspect it. Furthermore, he could singularly match New York’s intensity and rage and never showed fear of the intimidating rivals. Like his famous giant Husky-mix Roger, Cork always seemed only recently domesticated. And after he helped DoG win five titles, they unceremoniously dumped him to pick up Fort and crew. Why? Because the college kids didn’t like him. A lot of people didn’t. Is that why we don’t see Cork on the ballots? ↩

Gewirtz’s story has already been written and if Jonny G crossed the line one too many times and the Hall doesn’t think he was worthy of induction because of it, then Gewirtz’s failure stands out as the price one pays for short-term success at the cost of honor and pride. ↩

James Studarus was an interesting player: tall, rangy, stork-like with lethal range on hucks from both sides. Together with Hollywood and friends, the duo powered the feared UCSB 90s teams to three straight College titles then tacked on two more in Club pretty quickly. Like de Frondeville, the range provided by Studarus’ deep shots opened up the field for the Condors, and like de Frondeville I’m not sure the Condors win Nationals and Worlds titles without him. But now the caveat: Studarus wasn’t necessarily the friendliest of dudes out there. Studarus wasn’t an anti-spirit zealot in the mold of Mike G, but he wasn’t going to let the gray areas of ultimate hold him back from championship glory, either. He was nearly always accused — accurately, often — of traveling on his big throws. Why? Because his pivot foot was a fluid thing, nimble, spry, sly, and used to great success in his first niche sport success: hacky sack. Did he purposely travel often to gain an advantage? That’s not for me to say, but it was noticed by the community and it’s unclear if that’s why we are not seeing his name come up in nominations. Studarus later wrote a small handbook The Fundamentals of Ultimate and is now a photographer known for capturing the Northern Lights. ↩