The Great Britain National team used benchmark athletic measures to assess players in a rigorous way.

November 26, 2014 by Sion "Brummie" Scone in Analysis, Opinion with 8 comments

When asked to coach the Great Britain team and run trials, I was keen to ensure that they were as impartial as possible. Not easy. As it turned out, tryouts were the first step on our way to building – in under two years – the most successful Open team ever to come from the UK.

To set the scene, it’s October 2010. WUCC in Prague is a few months behind us, and most of those trying out had just finished playing at the European Championships. The best performing Open team from the UK, Clapham, had finished 10th – far below their aim of semi-finals – and had crashed out of European competition to the Swedish club Skogsyddans for the second consecutive year despite dominating their domestic competition. The gap between the UK and the rest of the world seemed wider than ever. Serious work was needed if the GB team was to be successful, and merely aping one of the UK clubs wasn’t going to cut it.

Having been recently appointed as Head Coach of the GB Open squad by the new manager – and long-time Clapham captain Marc ‘Britney‘ Guilbert – I was keen to see the best that the UK had to offer, and I didn’t want to rely on word-of-mouth (unlike the 2007-8 squad selectors).

I still needed to recruit a group of experienced GB players to help collect data about those trying out, but didn’t want any bias. We put out a general invite to the whole of the UK, and the interest resulted in a tryout with 50+ players in attendance from over 10 different clubs, a wide age range spanning nearly 20 years, and experience levels from GB veterans to people in their second year of playing.

Tryouts needed to be multi-purpose:

- To find a group of players that would have the potential to be world champions in just two years time;

- To find out where our strengths (and weaknesses) were as a team in order to guide individual player development; and

- To have any chance of success in 2012, we not only needed raw talent but we needed a group of players with the aptitude to be coached – moulded – into a team. It fell to me to come up with a way of assessing the current state of play.

Physical Assessment

I’d spent the previous three years training alongside a team of long jumpers under the tutelage of Colin Harris; Colin also works with high performance athletes on basic movement training for improving athleticism, and was a former military man who nearly made the Olympics. He had proven his expertise to me personally (having turned me into a half-decent athlete) so I wanted his input on the entire team.

Having no normative data on what should be expected of high level ultimate players, Colin turned to a more seasoned sport – tennis – for numbers. He took guidance from the Australian Institute for Sport (AIS), which have standards for a number of physical tests, as follows:

- Countermovement Jump test (single & double leg); essentially, just jumping as high as possible with a dip & arm swing.

- Plyometrics; single hopping & double leg multi-jumps for distance

- Overhead medicine ball throw

- 50m dash, with timing gates capturing the 5m / 10m / 35m splits

- 4 x 50m shuttle time

- Arrowhead agility test

- Bleep/Beep test

Where scores were unavailable from the AIS, other equivalent normative data was used. All players were shown what they were meant to do, allowed several practices if they wanted, and then two scored attempts at each test where the better of the two was used in the analysis. Afterwards, we collated the data and compared it to our targets.

It didn’t make for great reading. It turns out that ultimate players aren’t really at the expected standard, even for elite amateur sports.

Key findings (Oct 2010):

- Poor jumping technique in many players, to be addressed via basic plyometrics drills & coaching

- Right leg related activities (including left agility drill which turned off right leg) tended to score better than left leg activities, except multi-jumps which may be down to increased hip strength in left leg; all signs of imbalance

- Poor flexibility in many athletes resulting in poor running & jumping mechanics

- Lack of core activation in many players

- 90% of those who hit the 5m target failed to hit the 10m target, yet 20% of those who failed to hit the 5m target still hit the 10m target; essentially, power vs technique. Both need to be addressed, and targeted to each group

- 50% of those who made the 10m targets failed to hit the 35m target; require coaching in the change of mechanics from sprint phase to stride phase via body weight transfer training

- With less than 6% achieving all running targets, Colin was concerned that our players weren’t used to maximal effort training; this proved to be a problem for some players as the nature of ultimate is that we tend to take short rests compared to sprinters. Adjustment via education!

- Poor sprint mechanics & running form, to be addressed via coaching & running drills

- Poor speed endurance in the 4 x 50m; Colin would prefer a target of 28s yet only a few hit 30s. Players require training in change of direction when at max speed, and far more interval training.

- Those who performed well on the Bleep test were those who performed poorly on the power activities, indicating lack of fast twitch muscle

Again, I felt a lot more confident being able to provide feedback to players – including making selections – based on facts and figures rather than purely qualitative judgements. Colin was also able to see some imbalances – mostly between left and right results – and address that through the conditioning sessions we were given. Given players with such a wide range of ability, Colin had a tough job to put together a general purpose programme that addressed the key areas identified, but fortunately he was able to provide a variety of workouts then each individual was able to do more of the sessions that targeted their weaknesses and less of those that targeted their strengths. This put us on a road for strong overall improvement.

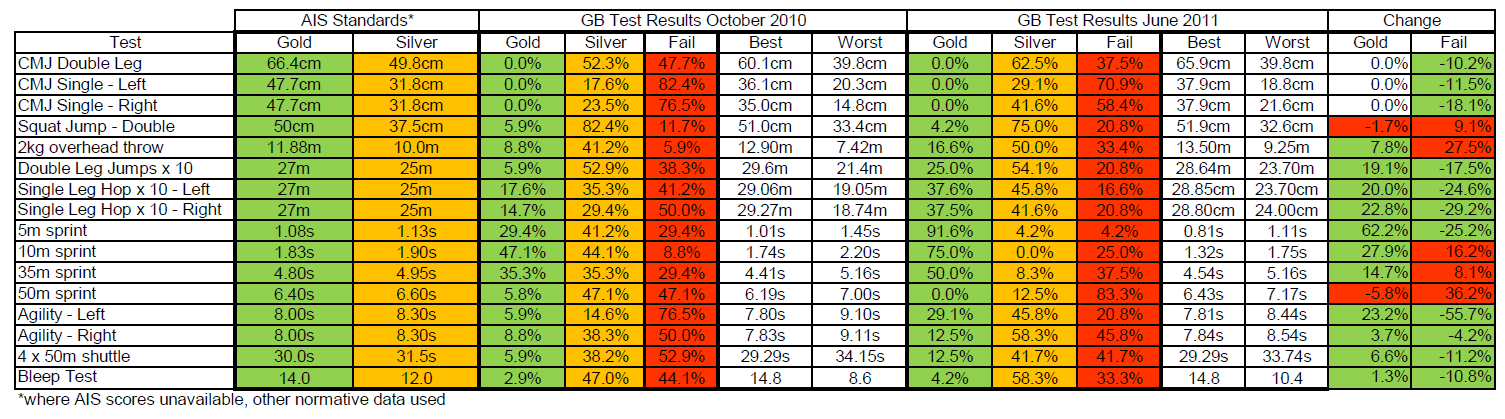

You can see the results here, along with the results taken later that season (note: we were forced to run outside in June, and a headwind meant the longer distances were run slower than expected). While the figures wouldn’t stand up to academic rigor (we were forced to change location, equipment, increased understanding of how to perform the tests themselves and not all the same participants in both sets of tests), the June results were nevertheless encouraging; we’d got the message across that we were serious about being world class athletes and were setting the bar high. We didn’t repeat this process in 2012 – it was too time-consuming, too few new players, and quite frankly we’d already instilled the ethos in our team that we were after. But it definitely worked for us to have a clear understanding of what we were working with, and it meant that Colin could write appropriate conditioning sessions for a wide range of issues.

Colin’s programme was also having clear results – just compare the percentage of players achieving gold or silver standards in October vs June. In October, only seven players made the gold standard over 5m, and the same number failed that test. By June, all players bar two made the gold standard. Bear in mind that these players were all already top calibre ultimate players – they already did “fitness” work for ultimate – but had never been assessed and had programs tailored to their needs before.

In part two, I’ll go into detail of how we performed an assessment of playing skills, how I used the data to guide my team selection and coaching plans for the first season, and look at the pros and cons of my approach.

For more coaching tips, Flik has a library of detailed drills for ultimate, practice plans and theory to learn more about ultimate. Train Better. Play Better.