April 2, 2013 by Peter Adam in Analysis with 5 comments

Towards the end of 2011, I watched my university team lose the semi-final of the Australian University Games. I say I watched, because although I was on the team, I didn’t play a single point. I wasn’t a bad player, but I lacked the athleticism to make defensive plays and, despite playing for four years and calling myself a handler, couldn’t seem to put together reliable offensive play.

Almost one year later on the dot, in the same competition, I played as a starting offensive handler and led my team to an 8-5 halftime lead in the 2012 AUG semifinal. Sure, I trained hard that year, but not hard as I could have (full time work and study came first), but after frustration at my lack of defensive pressure, I put nearly all of my focus into fitness and conditioning sessions. Apart from that, nothing else changed in my training between years. But I found with an increase in my fitness, every aspect of my game improved considerably, especially my consistency as a handler.

I never really knew why the ability to sprint faster and for longer was helping me pick better options and throw better throws, but a few days ago I came across an idea which might provide insight.

Malcolm Gladwell’s research into behavioral economics is, once again, providing insight into Ultimate, this time in his national bestseller Blink:

[quote]”Dave Grossman, a former army lieutenant colonel and the author of On Killing, argues that the optimal state of ‘arousal’ – the range in which stress improves performance – is when our heart rate is between 115 and 145 beats per minute… ‘After 145,’ Grossman says, ‘bad things begin to happen. Complex motor skills start to break down. Doing something with one hand and not the other becomes very difficult. … At 175, we begin to see an absolute breakdown in cognitive processing. … The forebrain shuts down, and the mid-brain – the part of your brain that is the same as your dog’s … – reaches up and hijacks the forebrain. Have you ever tried to argue with an angry or frightened human being? You can’t do it.'” (pg. 225)[/quote]

Let’s consider a scenario in ultimate. After a long cut or a big layout D, players’ turnover rates seem abnormally high. New players who panic and try to throw on stall one rarely make good decisions, and even experienced players see their error rate rise after a particularly high effort sprint. To me, it seems like those players who aren’t letting their heart rates reset before making a decision throw it away more often, and it seems like Gladwell and Grossman have the answer as to why.

Let’s move away from the psychology and look at the implications this has for ultimate players. First of all, it seems to suggest that if you get a huge block, you should never pick up the disc. Secondly, if you’ve made a larger than normal effort to get the disc, you should not be making decisions before your heart rate falls back to a decent level. But how long does that take, and is there a way to speed that process?

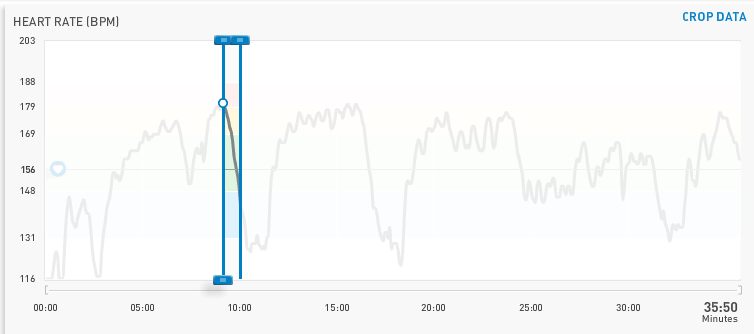

For an answer, I looked back at a set of training data I keep occasionally through the use of my Adidas MiCoach. The first graph is from the Friday just gone. I was pretty hungover, pretty full, and thanks to a partially torn ACL in October last year, quite out of shape. The highlight section of the graph is the period after I finished a set of ten 40 meter sprints with about ten seconds rest between each.

The left hand data point is my max heart rate, 180, just after finishing my final sprint. The second data point is when my heart rate finally went below Grossman’s upper limit, 145 beats per minute. That fall took 50 seconds. More importantly, as the session went on, the time to hit that 145 from my maximum heart rate lengthened. Any player who has trained hard will find it easy to infer that the time it takes for heart rate to fall after effort decreases as fitness increases. Grossman’s contribution provides a link between fitness and increased cognitive ability during a game.

This all seems consistent with my experiences, but there was one thing that was bothering me: if the brain shuts down at a certain heart rate, how do players still make good plays when they exceed 175 beats per minute? Gladwell again provides an answer, this time through an interview with Gavin de Becker, author of The Gift of Fear.

[quote]“De Becker does a similar exercise where his trainees are required to repeatedly confront a ferocious dog. ‘In the beginning, their heart rate is 175. They can’t see straight. The second or third time, it is 120, and then it’s 110, and they can function.'” (pg. 238)[/quote]

This perhaps suggests that the heart rate spike just before a catch from the stress associated with decision making is separate from, and in addition to, heart rate increases due to effort. Even more importantly, that spike can be reduced through practice and experience. In order to become calmer and operate in a higher cognitive state, players need to practice high stress situations to decrease ‘stress spikes,’ while also training hard to decrease their ‘effort spike’ in heart rate.

There are more ways players can use this information to improve their game. First of all, get into great shape, that one’s a given. Second, take a deep breath when you catch the disc. Lower your heart rate for two to four seconds if you’ve made an intense effort before looking for a dump option. Third, handlers should be looking to make more difficult throws early in a point or after easy dump resets, when their cognitive ability is at its peak. As they get fatigued throughout a point, mistakes come more easily. Finally, practice makes perfect. Add a throw/catch combination at the end of a sprint set, or practice absolute full speed catching. Imbed complex actions deep inside muscle memory so that when the mid-brain takes over, your hands know instinctively what to do.

Although I didn’t know it at half time in that semi-final, this isn’t the whole picture. Physically, I had progressed my body to a state where it was not an excessive drain on my mental capacity. However, I was unaware that I needed to condition my brain such that it would not negatively affect my body. 8-5 up at half, we lost a key player. I, along with four teammates who would go on to be selected in the Australian University Representative squad of 18, could not defend our lead against arguably the best handler in Australia and his squad. We choked, a phenomonom completely separate from the panic and brain shutdown that ‘stress spikes’ cause at maximum effort.

Gladwell provides insights into this process as well, but it is a subject for another article.