Lou Burruss' series on help defense hasn't had enough attention. Here's why it matters.

August 14, 2014 by Sean Childers in Opinion with 19 comments

Help defense is the title of Lou Burruss’ recent set of important articles, but I’m not sure they are getting as much attention or response as they deserve within our community.

This post tries to do both: Summarize the arguments underlying Burruss’ defensive theory, and add some comments from my own experiences from playing, playing with stats, and editing video analysis at Ultiworld.

The Series and the Arguments:

“Help-Man” defense is “built [on] strict man-to-man [fundamentals, but looks to create] temporary double-coverages. Although techniques like poaching and switching are employed… the general idea is to prevent [and frustrate offenses,] rather than generate blocks.”

Lou uses two different (though somewhat similar) arguments to conclude that help-man defense will become the norm in Ultimate; I will summarize them below.

1. The “Look at Other Sports” Argument

Premise 1: If you watch other sports similar to Ultimate, the predominant defensive tactic is help-man. The most obvious example is basketball, where the best players are double teamed and three players are used to defend pick and rolls — but it’s true in other sports, too.1 On average, the best athletes can not cover the best athletes; offense has an inherent advantage.

Premise 2: Zones, while occasionally used in other sports, are nonetheless used less than help-man schemes. They are more experimental/pace-changing than foundational defenses at the highest levels.

Conclusion: Ultimate is a new sport, but will eventually evolve in the same direction as others.2 Help-man will come to predominate in our sport; if you think otherwise, the onus is probably on you to describe why Ultimate is so different than other sports.

2. The “Athletic Disadvantage” Argument:

Premise: Only one team can have the best athletes.3

Conclusion: Because only one team can have the best athletes, every other contending team is unlikely to win a championship playing straight man defense. Instead, they should look to play defense that is some combination of smart, confusing, and tricky (in other words, help-man defense). And if you are a good player or good team who is not THE BEST player or team, then you should be thinking way more about your help man skills and schemes.

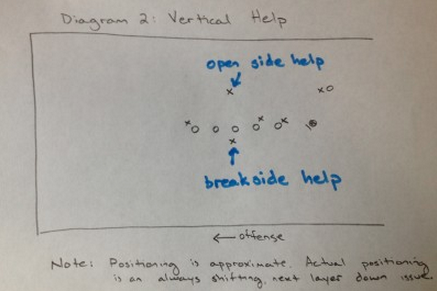

Burruss just finished the third article in the series; I mostly finished this before the third article was published. In the second, he began detailing specific help defensive concepts that apply to specific offenses, like in the drawing below. And the third article, the most specific of all, attacks handler help defense and specifically attacks a few pieces of poach-conventional wisdom.

How Did We Get Here?: A Behavioral/Economic Account:

Lou only briefly touches on how he thinks we got to this point, identifying “false positives” (good teams win without help-man, up until the quarters or semis) as a primary cause.4

I don’t think he’s wrong, but I do think there’s more to the story; this is yet another chapter in the novel of cognitive failure.

A lot of stuff happens in a single point of Ultimate, much more than you could possibly observe or fairly remember. That problem is only multiplied when you consider how much goes on in a game or at a tournament.

Naturally, our minds tend towards remembering the big events. Big throws. Big skys. And, importantly here, big blocks. The plays and the players who are best-remembered are those that generate blocks. This is the focussing illusion: what you recall, and how you judge, is based on what your mind focused on. While many little things along the way contributed to the game’s outcome, it’s easier to remember the big block.

The psychology problems here are incredibly intertwined with the statistical problems. It’s pretty difficult to statistically say who at Ultimate is “good” or “the best” at offense. You need to control for a person’s teammates; some throwers get Beau, while other handlers have to throw to me. You need to account for or measure effective clearing out in space5. You can measure completion percentage, but a dump turnover does not equal a huck turnover — and there are an infinite number of data points in between.

Effective defense is even harder to measure. This is a lesson from every sport that is knee-deep in quantitative analysis and it’s applicable to Ultimate as well. Brett Matzuka has already described this problem well in his argument that, especially with regards to defensive statistics, you should be looking at team-wide statistics rather than individual ones.

To effective measure everything that contributes on defense, you need to know so much. How many touches and yards did this player give up isn’t enough in itself. We need touches and yards conditional on the matchup. We need to know where on the field the block was generated6. Who is good at hedging off into the deep lane and causing the thrower to holster a huck which otherwise had a 70% chance of a score? What horizontal dump defenders can use length, anticipation, and hustle to put the most pressure in throwing lanes? Who is the best at both poaching off momentarily and recovering back to his assignment?

But think about how most teams are selected. Captains and coaches looking to identify good young defenders will always be a bias towards the player who made the bigger (and more recent) plays. I bet if you ask around the elite scene, you would find that many players who are new to an area make an elite team based on either their previous team or based on big blocks generated at tryouts.

In sum, there is a lot working against the emergence of help-man defense, the most important factor being that it is hard to see, remember, identify, and measure good help-man defenders. It’s far easier to put people in one-on-ones and (sometimes) keep track of who gets beat while (mostly) keeping track of who looked athletic. Given the limited exposure that players sometimes get in a tryout setting, that may even be a rational shortcut for captains who have finite time. That only causes the cycle to repeat and amplify itself, until a player finally plays up to the level that his/her athleticism can’t generate D’s — a Peter Principle of Ultimate, perhaps.

Reasons Help-Man Schemes Will Become More Popular

Yet despite the forces pushing against the establishment of help-man defenses, I agree with Burruss that they are only set to become increasingly popular. The subtext of Lou’s articles identifies two reasons you should expect to see more help-man: teams, who really want to win, will experiment to do so, and other sports have evolved there so ours should too.

There’s a more important reason: the explosion of Ultimate video. Filming the best teams in Ultimate is a borderline profitable7 activity.

So much video of teams like Riot, Scandal, Revolver, Fury, and Sockeye is now out there, and it’s very difficult for those teams to keep worthwhile plays, schemes, or poaches secret. Case in point: prior to Club Nationals last year, Seattle Sockeye watched film of Toronto GOAT and came out with help-man-type defensive systems that shut GOAT down8.

Both video and video analysis articles will accelerate the spread of help-man defenses that are successful. Bravo — perhaps the most athletic team in the world! — was consistently poaching off dead handler space, and switching marks to do so in their game against Revolver at Worlds. Expect lower level teams to quickly adopt those tactics, too. Scandal adopted one of the most consistent and aggressive help-man/ lane poach schemes of any women’s club team in 2013; now, thousands of players read through Martin’s breakdown of those schemes. Lou has argued in the past that the top teams in each division really do set the tone for competitive Ultimate; I think help-man may be spreading at that level even more quickly than he appears to admit. In particular, I was impressed with Ohio State’s individual and team defense this year. While Paige Soper and Cassie Swaford were stars that deservedly garnered attention, the clips we found of Ohio State’s defense showed an impressive, roster-wide heads-up techniques (Lou’s first help-defense principle) and tighter on-stage defense than off-stage marking; players knew when they were the hottest in-cut and responded appropriately. Ultiworld’s reporter, Alec Surmani, wrote that Fever showed “fundamental and occasionally poachy defense (pushing opponents deep and to the sideline), which often works well as a unit and generates turnovers.”9

The Teams and Players that Will Thrive

Datapoint #1: Alex “Dutchy” Ghesquiere comes to coach Scandal. Not only did their defensive scheme maximize the talents of stars like Jorgensen and Opi, but Duchy’s help-man schemes appeared to allow different players different amount of help freedom.

Ultimate players tend to talk a lot about offensive chemistry but much less about defensive chemistry. If anything, I think this might be backwards — but you can see how the norm and focus on “tight man” defense could cause the disparity. If your job on defense is to stay as tight to your man’s pocket as possible, and you are evaluated based on the number of blocks you generate, then it matters less who the other six players around you are.

But if you are employing a team help-man defensive scheme, then each player’s communication eagerness and style will need to mesh with the other. One stud defender who has no willingness to play within a system is no longer quite as valuable of a defender.

Teams with good coaching/leadership, an eagerness to learn and be coached, and defensive roster continuity will be more successful at employing help-man — this challenges one of the main funnel tactics of gradually moving players from D Lines to O Lines as the gain experience. Another thing to look for: similar physical attributes amongst the D Line personnel. From a practical perspective, help-man will require more switching and maybe even “cascade switching” as Lou terms it 10 — which is difficult to do if you are switching someone who is 5’8 onto someone who is 6’4. In the NBA, wing players who can guard multiple positions are increasingly valued; this will be the case as help-man takes off in our sport.

There are other player skills that are more valued in help-man defensive schemes than traditional “tight” man. Specifically I am thinking about the poorly-defined “work rate” skill that is used to describe players in other sports like basketball.

When I hear “work-rate”, I think it applies to players who have high endurance, good intelligence (plus an eagerness to learn), and a willingness to work hard on the defensive end even if it doesn’t lead to a huge play.

These players will become more valuable if help-man takes off. To be sure, players with both high work-rate and amazing athleticism will still be the best defenders: these are your Tony Allens, Avery Bradleys, and Roy Hibbert’s in the NBA world. But it becomes a misnomer to think that a help-man defense with poaching leads to less running — in fact, the recovery stage (after you poached and when you return to your original assignment) is often more running than if you had never helped in the first place. Talking on the field takes energy but is a cornerstone of help-man. And implicit in the help-man ideology are constant expected-value calculations while you are on the field — what little shifts in my mark can help my the other 6 players behind me, even if it doesn’t lead to my point block? Lou closes out his series with much of the same thought — that help defense has the reputation of being lazy, but that the reputation is probably undeserved.

The one area that I would love to see someone study more, either in the comments or in another article, is the differences between different help schemes at different levels and in different divisions. Lou hits on the obvious; you don’t want to poach off the star against a team who has one star player — even if he/she is occupying relatively dead space.

Other than that, what specific poaching strategies work better in each division? Should we be teaching help-man as a fundamental defensive tactic even to our youth players? I think the most interesting question of all is how should help-woman defense differ from help-man, given the relative field sizes for each. Does the female defender on the breakside rail need to move further off in order to contest deep space? Fewer women have cross-field over top and hammer throws, which also has implications for helping towards a trap sideline against a horizontal stack. And what about help-man defense in mixed — should mixed men always keep their head up because the opportunity for help-deep d’s is inherently higher? Help-man defense on the bigger semi-pro sized field is a separate topic in itself. As someone who mostly follows club open and some club womens, these are questions that I can ask and speculate about, but not answer decisively.

Football: over the top safety coverage allows corner backs to play tighter underneath; blockers almost always out number rushers and the top pass rushers are double teamed. Soccer: you would almost never leave a defender alone against a good attacker in open/valuable space. Lou makes the same points ↩

I will add one more premise that I think Lou probably believes, but doesn’t explicitly state: this evolution will happen quicker than some people expect ↩

Not mentioned in the help series explicitly but check out other articles and the comments. It really is key to understanding Lou’s theory, though I think he probably overstates it for two reasons. First, athletes have to be confident; if the athleticism gap between Revolver, Doublewide, and Bravo is narrow, it may be both indeterminable and rational for those teams to think they are the most athletic. Second, teams’ utility functions aren’t really national championship or bust — despite what they might say! Ironside likes being in the semis. So if abandoning man defense may increase a teams odds of winning a title, but also increase the risk that team doesn’t make quarters — that could be a negative utility scenario for the team ↩

“Part of the difficulty here is the sheer volume of false positives these teams get from this strategy. In the vast majority of their games, they are the superior athletes and the strategy is successful. The problem is that these games aren’t the ones they should be basing their strategies on. There are only a small, small handful of teams that are true contenders to make semifinals in Lecco or Frisco – the next strategic step for the top teams is to get better at tailoring their tactics, particularly defensive tactics, for their main opposition.” ↩

Did you know one of Riot’s favorite concepts is “cutter holding?” Consider this quote: “[Riot coach] Lovseth also praised Calise Cardenas, who was being covered by threatening deep defender Sandy Jorgensen for most of the game. Cardenas was often forced to sit on the rail position in the horizontal stack, keeping Jorgensen out of the play. “Calise did very well,” said Lovseth. “We didn’t throw it at Sandy at all.” At last year’s US National Championships, Jorgensen dominated the deep space and Riot got blown out by Scandal.” ↩

Giving your D Line a short field is more valuable than getting a block out of the back of the endzone and requiring your team to go the whole way. Yet even this is conditioned on further probabilities; what were the offense’s odds of scoring before the block was generated? ↩

probably more accurately described as a break-even ↩

Leaving Rehder as the lone deep, and having the other six players man in targeted spaces is help-man defense to me. Whether throwing zone for 3 or 4 throws to stop a pull play before switching into man is a bit more debatable ↩

Full disclosure: I edited that article. ↩

Lou notes this as a standard help-man tactic, but I am a skeptic. Frankly, I doubt there are many teams in the world that pull of a cascade switch more than 10 times in a single season. Basically, I don’t see this regularly happen against the teams I play, on the teams I play on (I think I’ve pulled it off once or twice in my career, and I’m an eager help defender), and I don’t see it much on video, either. It may be the one area where I found myself more pessimistic than Lou; we’ve got a long way to go to move beyond the one-for-one defensive switch, even though there are obvious benefits to momentary double team, followed by a momentary “half-team” in the dead-space, followed by a recovery that could go in any direction. The practical example here: Against a sidestack, the cutter defender fronts the isolation cut, someone helps from the back, while the front of the stack takes on two assignments momentarily. Once the iso cut is done, the deep defender takes the iso cutter who cleared deep, while the original iso defender cascade switches onto one of the two open front-stack cutters ↩