November 26, 2013 by Tiina Booth in Analysis with 6 comments

It was the best of times. It was the grossest of times.

It was the best of times. It was the grossest of times.

Stefani Leto, a parent of a young ultimate player, writes on the Bay Area ultimate website, “Whenever a parent of a daughter asks me what ultimate did for my daughter, I say three things: It gives them a voice, gives them a body, and gives them a tribe.”

On the other side of the country, Miami Dolphin Richie Incognito leaves racist and threatening messages on the phone of his teammate, Jonathan Martin. No need to repeat them. Just trust me that they are repellent on every level.

I have trouble carrying these two wildly opposing examples of team culture in my brain at the same time. I embrace and applaud Ms. Leto’s description of what our sport has to offer her daughter. I reject the easy answers to the Fins’ Fiasco: ‘Incognito’s hazing is a normal part of every NFL locker room. Martin needs to grow some thick skin and man up.’

What disturbs me most is the allegation that Incognito’s actions were sanctioned, and perhaps even encouraged, by his coaches and the Miami front office. They knew exactly what they were doing when they signed Incognito and the harassment of Jonathan Martin supposedly went on for a year and a half. While Incognito is personally responsible for his actions, as well as Martin for his, we cannot ignore the culpability of those with the most money and power.

I don’t want to veer into a full-blown analysis of athlete exploitation in professional sports, but let’s at least agree that most of the intense media focus has been on these two individuals and not on the institution itself. How can we, as ultimate players and coaches, look at the team institutions, or tribes, that we build every year and make them an accurate reflection of our core values?

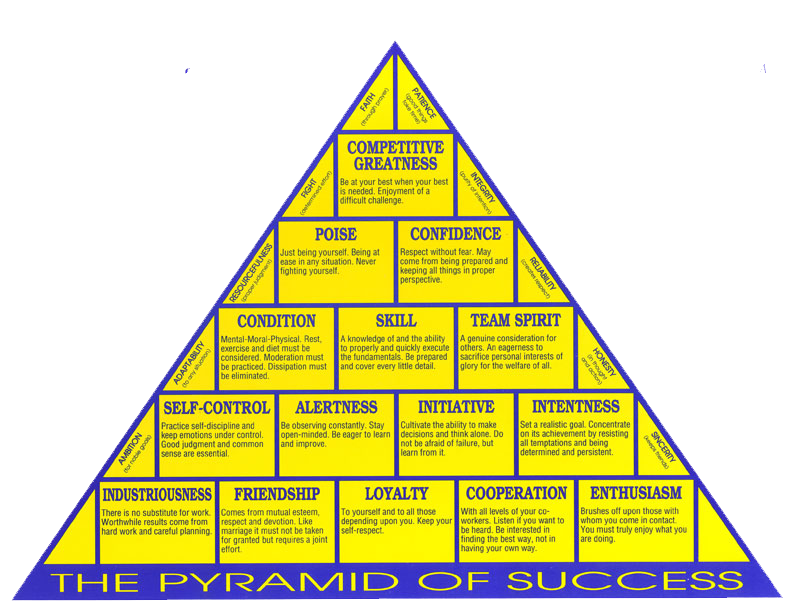

Joe Costello is an English teacher at Frontier Regional High School in South Deerfield, MA. He also plays and coaches ultimate and basketball. He is entering his fourth year as Frontier’s JV basketball coach and this year he is taking a concrete approach to establishing the culture of his team. Based on John Wooden’s Pyramid of Success, Joe has built a four-tiered model with Character as the base which holds everything together.

“I have Character —>Preparation—>Performance–>Results,” he writes. “I tend to think that team culture starts with Character whether you know it or not. It influences how you prepare and therefore how you perform.” He has drafted a Document of Standards (not rules) that everyone is expected to honor. As any good teacher does, he wants his students to understand the big picture. He sees everything they do, on and off the court, as “Pieces of Winning.”

These pieces include working hard at practice, getting homework done, using appropriate language and communicating with each other and the coach. While it is always easier to impose your beliefs on a team if you are an adult working with minors, leadership is leadership. Sometimes it means taking your team where it doesn’t want to go.

Some high school and college teams will understandably bristle under the suggestion that they need to take time to define and establish the culture of their team. Isn’t it enough to get sevens at practice? Why should we care how we present ourselves if the school doesn’t even acknowledge we exist? Can’t we just have fun?

If you are going to put energy into practicing, traveling, and competing, you might as well spend a meeting or two discussing what your team is all about. It may make all that practicing, traveling, and competing a lot easier. Do not let your team culture just happen. I can cite too many examples of ultimate teams, mine included, taking the low road of behavior, including racist, sexist, and homophobic slurs; vandalism; cheating; and good old-fashioned obscenities.

Basing your team on what has been done before is the comfortable way of doing things. Tradition and rituals can be important, but not if you are stuck in the past. Each year the leadership needs to take a fresh look at the new team configuration and figure out how to develop everyone’s potential. Alums may complain, but, really, it is not their tribe anymore.

Have a team meeting at the beginning of your season and maybe again half way through it. Don’t wait until there is a crisis to have this talk. A leader should try to be proactive rather than reactive. After discussing what your goals are for the season (more about that in a future column), consider these questions, or others, as a team:

1) What is our team approach to practice?

2) How do we want to represent our school/team/selves during competition?

3) How do we deal with conflicts among teammates on and off the field?

4) How do we handle losing?

After coming to agreement about these answers (this could be a long meeting), put together some standards of behavior. These could be:

– We will all arrive to practice on time and stay throughout the entire practice.

– We will respect the directions of the leadership.

– We will work hard at every practice and game.

– We will encourage each other to work hard and succeed.

– We will respect all players, on and off the field.

These rules may seem absurd to some of you and insubstantial to others. That is just fine. Every team has different goals and varying degrees of commitment. What is important is to meet, listen to everyone’s voice, and figure out the standards on which you can all agree. It can be your mission statement or your code of conduct or your constitution. All that really matters is that this structure will help guide the team throughout the season. And remember that this is a living document that can be amended when needed.

A team’s performance is strongly linked to its team culture and each individual athlete is a direct representation of their leadership. Athletes excel when a fair, strong structure is provided by their coaches and captains. John Wooden proved this over and over. I would guess that some of our finest ultimate teams, in every division, have spent time on this very issue. How can you get to your final goal without knowing which road to take?

I will be tribeless this spring, for the first time in 23 years. It is my choice, of course, and I hope to eventually find a new one. But I still dread that first warm spring day when I won’t be at practice, watching my team shake off the dust of winter. Everyone deserves to be part of a tribe. Especially Jonathan Martin.