Core skills to understand how to attack and defend the most valuable real estate on the ultimate field.

January 10, 2017 by Ben Wiggins in Opinion with 4 comments

This article is presented by Spin Ultimate; all opinions are those of the author. Please support the brands that make Ultiworld possible and shop at Spin Ultimate!

Endzone strategy has steadily become more standardized over the past two decades. In the past, many teams would use extreme variations of endzone spread formation, cutting from the back of the stack, multiple resets, etc. Now, teams are coalescing to a set of basic principles that make endzone offense more effective.

These principles almost all push teams towards higher efficiency, towards the most wind-ready strategies, and towards a set of fundamental skills that in ten years time are likely to be core to every player’s education in the sport.

Endzone Offense

The central goal of endzone offense (EZO) should be to score without needing to cover extra yardage with throws. From one yard out, a goal could be scored with a throw of a single yard or a throw of 20+ yards, but the latter will generally increase risk for the same point value.

Most successful teams score the majority of their goals in the front 3-5 yards of the endzone. That scoring band of space across the field is the most valuable part of the goal. This calls for shortening throws whenever possible and avoiding difficult positions on the sidelines.

Positioning

Shortening comes primarily from targeting the front player in a vertical stack. This player is positioned close enough to the thrower to allow ‘flippy’ throws that happen quickly and don’t require a full windup. This short distance should be established even if that means that the primary target is positioned outside of the endzone; this starts the offense working to create uncertainty in the marks and sustainably gain short yardage when there is no threat of a deep cut.

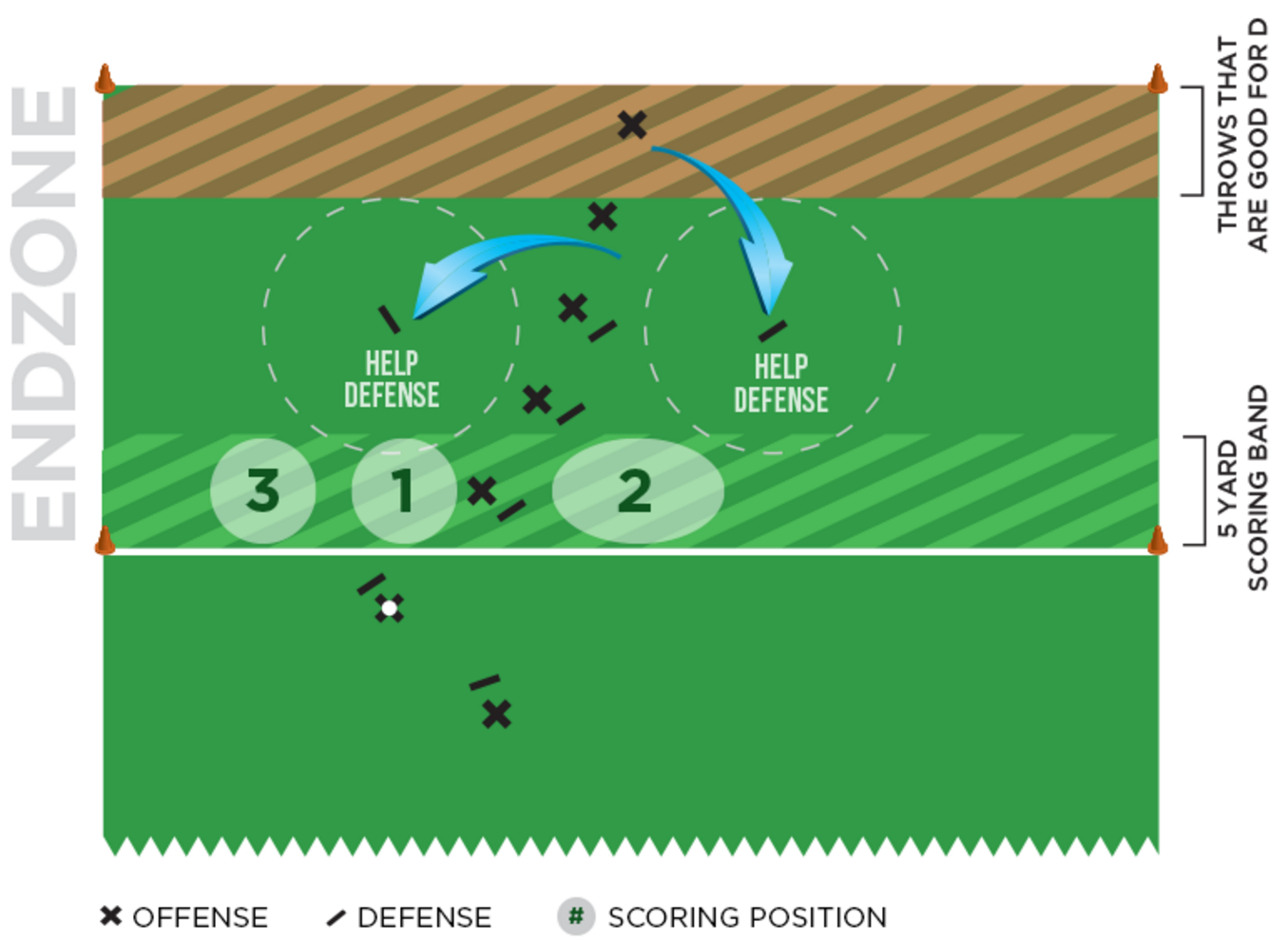

When possible, the thrower should face and work together with this primary target player. When this target happens to be in the endzone, both of their lateral movements are worth a goal, which cannot be said for the reset player. The defense traditionally counters by assigning one of those lateral movements to the defender on the target and the other to the marker, who sets a standard force. Modern EZO tries to gain a numerical advantage by offsetting the target into the live side of the field, creating three areas in the scoring band which can be used to score goals to the target, as shown in the following diagram:

The scoring positions are:

- The middle: The in-between space is on the break side of the defender and the live side of the thrower. A standard force does not assign this space to a defender.

- The live side: Using the threat of the 1 or 3 spaces, a smart cutter can use fakes or quickness to get open for an easy throw on the live side.

- The break side: This space can be used either by the thrower breaking the mark or ‘bending’ the mark by throwing around a mark who is cheating in to cover space #1.

When the target is not in the endzone, throws to spaces 1 or 3 allow a second throw to the break space without a mark if other cutters can take advantage. Throws to 2 may allow continuation opportunities on the live side, or quick target players may be able to break the mark if the defender overruns their position.

Theoretically, this formation requires disciplined spacing and quicker, flippy throws. If that cost can be met, the return is the use of three spaces that can be used against two defenders, meaning the offense should be more likely to score than not on any given play.1

If the thrower to target connection isn’t open, then the thrower can use the single reset or dump player to make their next move. With the reset positioned at a diagonal on the live side, they are likely to be open in one of three ways:

- If the defense guards a backfield move, the reset can move into the endzone and score.

- If the defense guards a scoring move, the reset can move towards the breakside. If the throw is on-time and accurate, then the reset will often have a momentary open lane to the breakside for an unmarked scoring throw.

- If the defense poaches off of the reset to stop scoring throws to another player, then the reset can choose their reception location based on what is most likely to lead to a goal. Catching the disc flat footed is often the worst of the available options.

The rest of the offensive players are aligned in a vertical stack. Ideally, they position in an extension of the thrower-to-target line, allowing the thrower to quickly recognize any poaching. Against a team that plays pure person-to-person defense, those other five players should not be involved in any way in the first throw.2

For the offense to avoid moving towards the sideline, only one reset is positioned behind or lateral to the disc. Each extra player outside of the endzone is another defender who can poach or prevent goal throws to other players. Having a single reset allows an easier reset throw and reduces the number of defenders who can help without allowing a goal-scoring throw. Systems with multiple resets can obviously score if the players make good decisions, but their major strategic value is as a change of pace against teams who aren’t ready for a different look.

EZO In Motion

After any non-scoring throw, the offense resets the three person formation of thrower, target, and reset. When the EZO does move towards the sideline, the positioning shifts to maintain advantages as best it can. The front-of-the-stack target should shift to recreate balanced 1, 2, and 3 areas, though these areas become smaller. The thrower-to-target line is more diagonal in these cases.

On the break sideline, the reset can maintain the same diagonal positioning as if the disc were in the middle of the field. On the force sideline, the reset cannot be at the same diagonal,3 so they line up at the next best position: lateral of the thrower and on the break side (closer to the middle of the field). This allows an upfield scoring cut and a backfield dump cut option. If the dump throw regains some middle-field position, then the offense can reset into the primary formation.

The last offensive fundamental to include is that throwers should look to attack with give-go moves on any throw towards the live side. Because the mark must respect breakside throws, the thrower will have a position advantage to the live side. This is most important on throws to a stationary dump, and even more important on those throws from the break sideline to clear space.

Endzone Defense

Good endzone defenders know that they will give up some goals, but their success will be measured in the overall decrease in scoring rate of the opponent. If you can bring an opponent’s EZO from 80% down to 75%, then you are winning even if they score three out of every four possessions. This can be difficult to appreciate in the moment, which is one reason why coaches and longer-term vision can be so valuable to teams.

Likewise, strong EZO players and teams aren’t satisfied with simply scoring. An unsustainable score (like a huge unlikely sky or a back-corner toe-drag) can be celebrated as a big play but should be systematically avoided. If that is what it takes for you to score, then you have bigger problems and good defenses celebrate this evidence of systematic success.

Given the 3-space formation discussed above, smart defenders help to the front of the endzone and tempt throws towards the back of the endzone. This effort is more often rewarded in windy situations and with throwers who are either stressed, pressured, or less-skilled. Wasted yardage (the distance from the front of the endzone to the location of the scoring catch) is also a way to chart EZD efficiency.

Help From The Back

There are few absolutes in ultimate, but one maxim that comes close is that any defender guarding one of the rear two players in an endzone stack should be looking to help into the front scoring band. While this means leaving offensive players in the back less tightly guarded, these are players that are farthest from the disc, require the longest throws to reach, have the least likelihood of seeing the thrower and making eye contact (because of the people between them), and who cannot simply run away from the defender because they’ll be out the back of the endzone. Those defenders should help enough to make a difference in the mind of the thrower focused on the front two cutters. If you help less, you may as well not help at all. But if you can help enough to dissuade even one easy goal throw, then you will give other defenders opportunities at additional blocks.

Splitting the back two defenders such that each defender can help on one side of the scoring band (as seen in the diagram at the start of this article) is nearly always beneficial — especially in the wind. The hammer or blade that would subvert this strategy is a long, looping, wind-impacted throw that can float, be dropped, or simply fly out of bounds. Any defender should encourage this throw over a simple flippy throw into the scoring band.

Why don’t more teams play defense like this? Simply put, it violates fundamental rules about defense in the rest of the field. We tend to oversimplify our teaching of ultimate, and so we tell players to never leave their person, to trust their teammates to do the same, and to treat letting their player catch a goal as a cardinal sin. The reality is that these are poor maxims in most parts of the field — and they completely break down in the endzone. Your goal is to stop the other team with your team, and difficult throws to any individual player might be a positive, though you’ll have to get over the bruised ego of “failing” in your one-on-one matchup. Coaches can accentuate the team goals by being clear about endzone outcomes that are examples of excellent defensive execution but which still result (in that particular instance) in an unsustainable goal.

Buzz Switching

Against handlers, a ‘Buzz’ switch4 can be used to help against the advantaged give-go moves to the live side.5 In this switch, the reset defender drops into space to cover the throw-and-go handler. The previous mark becomes the mark on the new thrower. This works well because the marking angle is generally similar to the position of that player, so that the breakside is not left transiently uncovered. As with any switch, the angles are important and take time to perfect, and this switch can induce mismatches that might be problematic for the defense later. In practice, this switch can be disconcerting to an offense and disrupt an EZO flow.

***

It is important for all players to realize the ultimate is not played on a whiteboard. This standard EZO scheme only works when players are well-versed in the individual fundamentals; if you want to win a major tournament, then you have to walk onto the fields knowing that you can score an endzone goal from your weakest thrower to your weakest cutter.

Defenders are not simply forlorn losers in the numbers game; they can use quickness and dynamism to create chaos in an EZO plan. Moreover, they don’t have to win a single particular play in order to have performed successfully in a game. Virtually every team will have at least five EZO possessions in a game, and your success rates in those ten moments will have a major impact on the final score.

Please note that this does not mean “offense has an advantage”: this is a meaningless statement. The comparison that matters is the comparative success of two scoring rates: Offense A-vs-Defense B compared with Offense B-vs-Defense A. This comparison is meaningful and also takes into account factors like wind and fatigue. ↩

As you might expect, no good defense plays purely person-to-person, as I will discuss that in a little bit. ↩

They’d be sitting on the bench to do it. ↩

See an example at the bottom of this article. ↩

The Buzz switch is named after the Buzz Bullets teams who made it popular. If we’re being accurate though, this movement is probably equally attributed to MUD, Huck, and UNO, who made similar tactical developments but who had less media coverage. ↩