As restrictions on gyms and track access loosen, make sure you return safely.

June 30, 2020 by Patrick Kelsey in Opinion with 0 comments

Tuesday Tips are presented by Spin Ultimate; all opinions are those of the author. Please support the brands that make Ultiworld possible and shop at Spin Ultimate!

This article was originally published on the Breakside Strength & Conditioning blog. Breakside S&C is owned by Ultiworld Inc.

The coronavirus pandemic has kept us away from the gym for almost three months. Many of us have also had our seasons truncated or outright cancelled. With an extended period of detraining behind us and a potentially long training timeline in front of us, there are many questions about how to best return to the gym both effectively and safely.

Below, we address how to safely return to the gym — or playing ultimate, for those able to do so!

I’ve been going crazy. Can I get back into my old training regimen?

Not right away.

The most pressing concern for returning to training is injury risk. The risk of sustaining an injury is heightened after an extended lapse, both on the field and in the weight room. Most non-contact injuries are sustained during periods where athletes are transitioning back into training following a period of inactivity.

We recommend that you come back by using a 2-4 week ramp up before re-entering a periodized program again.

This ramp up will be based on The FIT Rule, which controls frequency, intensity-relative-volume (IRV), and time of rest interval.

Frequency

Frequency should begin with only two weight training sessions in the first and possibly second week back, progressing to three times a week. If muscle soreness dissipates within 48 hours after the end of the weight training session, then higher training frequency may be included.

Intensity Relative Volume

The formula for IRV is (Sets * Reps * %1RM expressed as a decimal). Basically, this controls for both how many reps you’re doing and how difficult they are.

IRVs of greater than 30 are not recommended in the two weeks following a period of inactivity.

So don’t do 10 sets of 10 reps at 60% of your one-rep max your first week back.

Rest

It is recommended that all weight training activity uses a 1:4 or greater work to rest (W:R) ratio during week one and a 1:3 or greater W:R during week 2.

Have I lost all my strength?

As always, developing functional strength is one of the best safeguards against injury, which leads to the above question.

Short answer: No, but it depends.

Brief detraining periods result in only small decreases to strength, but longer periods of inactivity (including a lack of in-season training) result in much larger strength losses. Additionally, if you engaged in a program that emphasized muscular endurance (think “100 air squat challenge”), your maximal strength may very well have gone down more than had you just done nothing. High rep, glycolytic work has the potential to move your adaptation in a completely different direction. Your body will adapt to what you ask it to do.

So what do I do to get strong again?

This all depends on your experience level.

If you are a beginner in the weight room, start with an empty bar for a couple of sets and do a set of five reps. You’ll want to be incredibly deliberate about maintaining full body tension. Lack of tension is one of the riskiest errors when under the bar. We use the cue “fake the weight” — pretend the bar is far heavier than it is.

Overloading the bar too quickly is one of the best ways to lengthen your hiatus from the gym. Once you have done a few sets with just the bar, you’ll want to perform some positionally challenging versions of the heavy lifts — things like deficit deadlifts and pause squats — that really force you to brace in a challenging position and naturally limit the amount of weight you can load onto the bar. We’ve adjusted the tempos and loads of our squats and deadlifts in our Return to Lifting Program to emphasize control over weight.

For experienced lifters, your strength is very persistent. You are almost certainly able, even after a three month layoff, to work up to your 85% or even 90% of your 1RM weight. Don’t do that. You will be able to finish the set, but you will not recover in the way you’re accustomed to. You will be sore for three, four, maybe even five days. The last thing you want to do is risk injury or extend your time away from the gym.

So in your first workout back, the one where you “rip the scab off,” you’re going to leave a lot of weight off the bar. It’s ok!

Let’s say you can normally squat or deadlift 225 for three sets of five. First day back, I think I’d probably go up to 135, maybe 145, maybe 155. And just do one set of 5. The second workout, at least 48 hours later, come in and do 145, 155, or 165 for three sets of five. For the third workout, go to 175, 185, or 195. Again, these are percentage based recommendation based on an ability to do 225×5, so our percentages here are all below 85% of this capability, or 75% of 1RM.

In week 2, we can repeat this rep scheme.

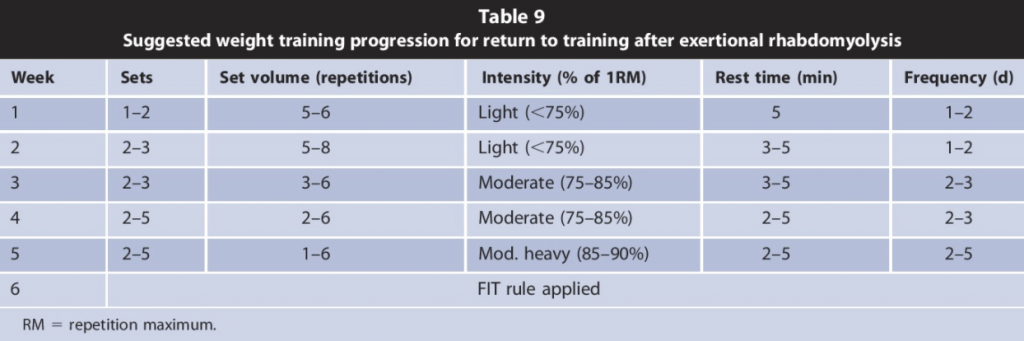

In the following two week block, we’ll work between 75%-85%. The chart below includes an additional 2-week block for a total of six weeks (this recommendation, however, is based on a return to play after rhabdomyolysis, a serious injury requiring much more recovery.)

How should I get back to conditioning?

Relative to what we normally do as ultimate athletes, we are all almost certainly significantly deconditioned. We can apply the FIT rule to conditioning as well, and use an easy-to-remember 50/30/20/10 pattern to return to conditioning.

That is, the conditioning volume for the first week would be initially reduced by at least 50% of the uppermost conditioning volume on file, and by 30, 20, and 10% in the following three weeks, respectively, with a 1:4 or greater work:rest ratio (W:R) in the first week, and a 1:3 W:R or greater in the second week.

So, don’t just try to jump back into your usual routine: ease back in over a period of four weeks.

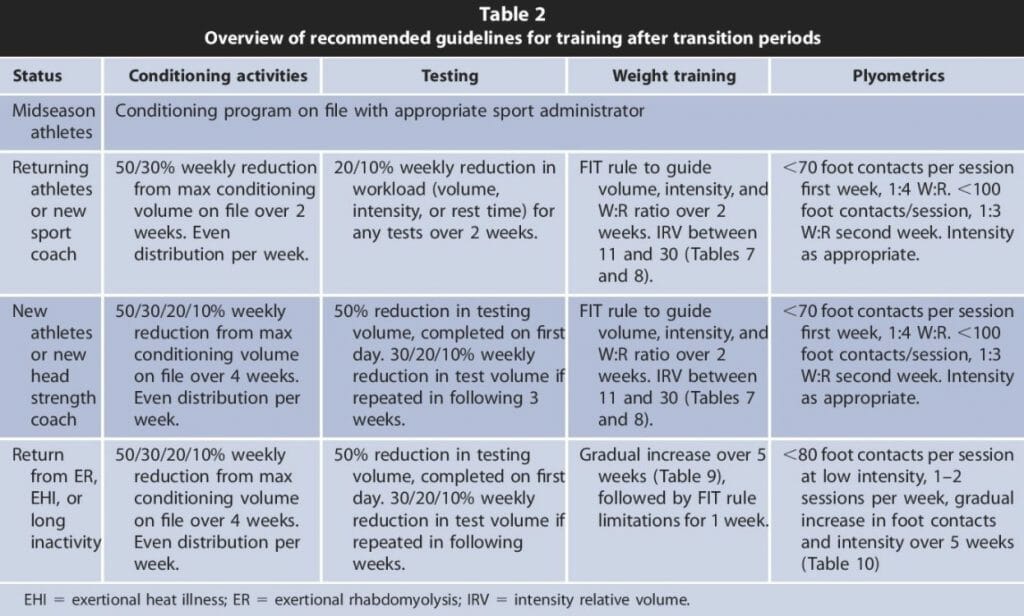

The chart below gives a nice summary of many different types of activities and the recommended strategies for return to training. Right now, our season is as far away as it has ever been, but there is still a great reason to build an aerobic base. We’ll be releasing more content on the best strategies to do this as the season approaches, but for now a few things to focus on are endurance, work capacity in accessory strength movements, breathing, and heart rate variability.

How about speed and agility work?

The real question surrounding speed and agility work is not what exactly to return to, but when to return to it. In general, ultimate players experience tremendous volume during their playing season, which means we normally would be very selective with the speed and agility work we prescribe. With the season cancelled or, in some cases, severely reduced in duration, we’ll want to adjust volume up gradually for two reasons: building specific work capacity and adapting to eccentric force production.

If you’ve been doing home workouts only, you’ve probably sacrificed complexity of movements and reactivity. The increase in volume will have to come after a gradual ramp up, just like our conditioning with the same the 50/30/20/10 rule.

For these workouts, we want to think about foot strikes. The ramp up workouts should be about 120–140 foot contacts for in-season athletes, and plyometric workouts in the first two weeks should not exceed 70-foot contacts in week one and 100 in week two, according to the National Strength and Conditioning Association.

Linear First, then Agility

Once linear sprints can be performed without increased muscle soreness and the athlete is able to perform them at their previous training volumes, then agility and change of direction drills can be added.

To start, focusing on simple repeat sprints is a great way to both increase your work capacity and keep the technique demands relatively simple.

After about two weeks of linear speed work, you can start to think about adding change of direction. Be sure your deceleration drills increase intensity gradually. This can be done with percentage effort and drill selection. The 5-10-5 is short and doesn’t get to full speed; flying 10s involve gentle deceleration. (Each 5-10-5 is about 16 footstrikes; a flying 10 is about 20).

***

If you’re looking for a program to help you get back to the gym and training safely and effectively, check out a Breakside Strength and Conditioning membership starting at just $10 a month.