A letter to ultimate frisbee.

March 22, 2022 by Gabriel Hernandez in Profile with 0 comments

I’m retiring from competitive ultimate frisbee.

This choice has been almost two years in the making and I’ve gone back and forth on it numerous times. However, before I dive into the motive for this hard decision, I felt compelled to reflect and reminisce about my time in this sport.

It all started my freshman year at Stanford in the fall of 2014, when my roommate Mike Becich said, “Hey man, they’re having tryouts for the ultimate frisbee team this weekend. The team is really good and you should come check it out.” At the time, I could have never imagined what that invitation would eventually lead me to, but I accepted it nonetheless. It was at tryouts that I first held an Ultrastar in my hands and realized what this sport could be. I watched people bomb full-field hucks. I watched people layout for tough catches. I watched someone get absolutely roofed for the very first time. I was hooked.

For the next four years, the team became my biggest focus outside of school, and I worked tirelessly to become the best player I could be. Some of my fondest memories occurred in this short time frame, and I’m forever grateful to the people that made all of those moments possible.

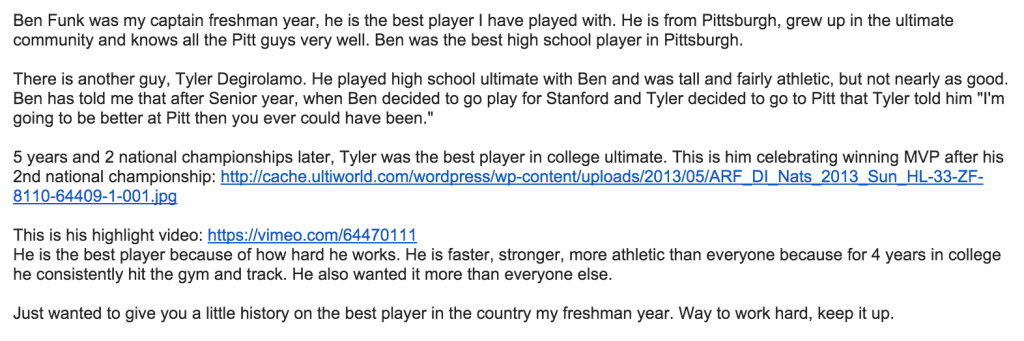

I’m thankful for Ryan Thompson for being my first (and best) ultimate frisbee coach. I’m thankful for captain Elliott Chartock for investing in me as a freshman and motivating me to work hard to compete with the best. Below is an email he sent me freshman year:

I’m thankful for Mike and his invitation to tryouts, I’m thankful for Allan Ndovu and his role in helping create the Rookie Dynasty, and I’m thankful for all the members on the team that helped shape my experience those first few years. The veterans set examples for us that motivated us to work hard and improve, and we as rookies took it upon ourselves to be competitive with each other as we invested time and energy into the sport.

As a junior, my role on the team began to change from inexperienced D-line cutter to starting D-line handler. Coach Ryan Thompson threw me into the role that autumn and set me up for lots (and lots) of turnovers and eventual growth in the decision-making areas of the game. This was the year that Stanford finally made it back to Nationals for the first time since 2011, and it was the first time that I got to experience what that level of competition was like.

We battled hard that year and fell 2 points short of our goal to make the elimination bracket, but I learned a lot from the experience and it set me up for opportunities with Austin Doublewide and the Dallas Roughnecks. That summer, I played in my first AUDL game, I experienced what the highest level of club ultimate was like, and I began to make friends and connections in ultimate that spanned the entire country and beyond. Doublewide made it to the championship that year and I learned what it meant to fight through the elimination bracket at an elite level.

In addition, I got the opportunity to play with Comunidad El Oso in the Colombian equivalent of Club Nationals that year. Elliott and I got to travel together and experience ultimate through the eyes of Colombian culture, which further inspired me to grow as a player so I could have more opportunities to make connections like these through the sport.

Senior year finally came along, and I couldn’t believe how quickly the years had gone by. As the previous year’s Men’s College Breakout Player of the Year, there was a lot of pressure to fill the shoes of the veteran players that helped us get to Nationals the year before. Our team was a lot younger, and we spent a significant amount of time developing our freshmen and sophomores early in the season.

One of my favorite memories that year was something that we called “Gabe and the Sophomores,” where coach Ryan would call out a line that is exactly what it sounds like. The goal was to help develop those 2nd-year players so they could fill more sizable roles downfield, and also to teach me how to quarterback an offense with my voice, body language, and decisions. This experience was incredibly fun, and it can be summed up with this picture:

We had another successful season that year and were able to make it to Nationals for the second year in a row. I’m sure most of you are familiar with the game-to-go at Regionals that helped get us there, but what most of you probably don’t know is how well the rest of the team played that game. It was a windy game with a lot of turnovers, and I’m so incredibly proud of how our entire roster came together to grind out the resilient comeback win.

College Nationals that year was a conflicting experience. In some ways, it felt like a culmination of everything I had worked so hard for the previous 4 years. The Callahan and Team Spirit Awards were both things that overjoyed every member of our program, including me. At the same time, however, the competitor in me was frustrated that I couldn’t give my all in my last college tournament with the team. Needless to say, this event was an amazing way to end my time at Stanford. It marked the end of a 4-year period that was, without a doubt, the most memorable and cherished time in my ultimate career. The people that were a part of those moments will forever hold a special place in my heart.

Check out this article by Stanford Club Sports and this one by former Coach Josh Kaplivsky for additional perspectives on this time period. This highlight video is a glimpse of my favorite season with the team.

After graduating in 2018, I moved back to Dallas and did not play ultimate that summer. I was slated to have surgery to fix my torn ACL, and I was transitioning into grad school and teaching in Dallas through Johns Hopkins University. This period marked perhaps the most demanding time of my life so far, as I had to balance PT, full-time teaching, and full-time grad school.

The Hopkins team, however, was gracious enough to let me be a part of their squad for my 5th year of eligibility. I flew out to a fall tournament to serve as an extra coach during recovery and I played in my first tournament after surgery in February of 2019. As a commuting player, it was much more difficult to find the same experience I had in undergrad, but the team welcomed me with open arms, and I was able to form valuable relationships in my limited time with them.

Immediately following this 5th year season, I received the opportunity to play in the first-ever Color of Ultimate game, an unforgettable experience. Getting to meet and share the field with countless other POC was so incredible that there aren’t really words that can capture it. The best quote I recall from that event was, “For the first time, I was able to look up during a game and not feel like I was one of a few.”

This led straight into an AUDL season where the Roughnecks made it to the Championship game against New York and I was given the opportunity to sing the National Anthem in the midst of several immigration changes implemented by the Trump administration. We fell short that year, but it was an honor to get to play on that stage with the team.

Growing tension in the country that year made a lot of things uncertain, especially for my extended family. Coupled with a Club Nationals that was located in a place where I could see said family members daily, I felt compelled to write this article about what I was experiencing at the time. My identity as a Latino in the country and within the sport was always something that I knew wasn’t super common, and no one ever really taught me how to navigate those spaces. In fact, my mom’s initial response to my attire during the Callahan ceremony my senior year was this: “Won’t they take away the award because you’re wearing a Mexico jersey?”

The fact is, I don’t think anyone ever truly learns how to best celebrate their identity as a minority without running into thoughts about tokenism and power structures. All I knew was that I wanted to share the cultural dissonance I was experiencing in hopes that I wasn’t the only one. The feedback from the article was overwhelmingly positive, and I felt motivated to continue to compete at the highest level while simultaneously shedding light on diversity issues within the sport.

Following the 2019 season, I flew out to Santa Barbara twice in early 2020 for the Beach of Dreams and Color of Ultimate showcase games. I was excited to hit the ground running with the Roughnecks and Doublewide that summer. Up to this point, I had devoted over five consecutive years of my life to a sport I had grown to love… and then the pandemic hit.

As I’m sure most of you experienced, whatever normalcy that existed before that moment in March 2020 simply ceased. The world was thrown into a new era and, for a while, I retained the same level of drive and commitment for ultimate as always. Though playing had halted, I wanted to continue to use my energy to highlight diversity and inclusion issues in the sport, which led to one of my proudest contributions. With the help of Shanye Crawford, AJ Beard, Lexi Garrity, Kelvin Williams, and Dillon Larberg, we were able to host an Anti-Racism Discussion Panel through the AUDL’s platform and raised over $70,000 for the Colin Kaepernick Know Your Rights Camp. That same summer, I joined the AUDL Inclusion Initiative Committee with high hopes of helping push the league into a more intentionally inclusive direction, and it was there that I began to learn that these problems stemmed from issues that were deeply rooted in the very fabric of our American society. It was there that I began to realize how ultimate frisbee likely wasn’t going to be the trailblazing model of diversity I once thought it could be.

There’s a reason so many people have issues with the AUDL. There’s also a reason why so many people support it. It has become the most popular platform for ultimate because it markets itself as a product where the “highest level” of ultimate occurs. Regardless of whether you agree with the previous statement, I think that the league’s product aligns with what society has historically valued in sports, which is the exact reason why this model is so hard to change.

For example, when the AUDL was considering hosting a bubble tournament in 2020, I reached out to the league with an idea for using the unique season as a way to highlight POC players in the sport – think of the Disc Diversity Con10ent Tour but with the AUDL’s resources and coverage. The main idea was for each participating region to field a team using POC from the area and to host a playoff-style event to crown a champion. However, I was told this was not possible because the league had made an agreement with their sponsors to showcase the best players in ultimate, which by their definition meant that they couldn’t bench all the white males that made up the different teams. Additionally, I was told that this suggestion would blur lines between teams and complicate the traditional funding structure the league uses through its owners.

Though the 2020 season was ultimately canceled, it became obvious that the league’s main priority was not to be diverse or inclusive; it was to market their version of the sport until it became profitable. This didn’t mean that they weren’t ready to support initiatives to help increase representation; it simply meant that they wouldn’t do it at the expense of their product.

I don’t necessarily fault the AUDL owners and shareholders for this unfortunate reality. They’re passionate about professionalizing ultimate and, quite frankly, they’re entitled to use their money in whatever way they think will best accomplish that goal. The root of the problem is that the AUDL, much like every other organization in American society, is subject to the capitalism that drives our economy. That’s why it is exciting to observe the PUL’s creative attempts at creating what seems like an alternative grassroots funding structure, and only time will tell how sustainable this model is. In any case, questions like “Whose money is it?”, “Where is it going?”, and “Who decided what the best way to use it is?” will always be at the core of these debates and, given that ultimate is a small-market sport to begin with, it’s hard to see where the quickest growth will come from if it isn’t through the willing hands of the rich.

It was at some point in the summer of 2020 that the aforementioned frustrations combined with a lack of playing opportunities made me take a step back from ultimate. The time that was once used for lifting, throwing, and track/field workouts was now being used for a variety of other things and, for the first time since the fall of 2014, ultimate was no longer one of the main priorities in my life. The competitor in me still yearned for an outlet: in July 2020, I was first introduced to disc golf.

A few local ultimate players invited me out to LL Woods park in Lewisville, TX, and I proceeded to shoot 10-over par using only an Ultrastar. A few weeks later, they invited me to Veteran’s Park in Arlington, and Colton Green let me borrow one of his putters so I could get more distance on my tee shots. I shot 4-over par that day using his putter and the Ultrastar, and I was naturally inclined to try to shoot under par. That same day, I bought a driver and a midrange from Dick’s Sporting Goods and started pushing myself to accomplish that goal. A few weeks later, I entered my first mini-tournament.

By this time, I had accumulated a handful of discs and used a drawstring bag to carry them around. I played in the amateur division and shot +3 to finish in 4th place. At the time, this particular mini was giving cash to amateurs and I managed to get last cash for $15. I vividly remember being surprised when they called my name out at the end for my very first “winnings,” and from that point on there was no going back.

Since then, I’ve earned about $2,200 in store credit and $9,300 in cash, and I’ve come to the conclusion that I want to see just how good I can get. My athletic peak is still a few years ahead of me, and I’m ecstatic to push myself that whatever limit exists for me. It was hard deciding to give up competitive ultimate for the sake of disc golf, and I still struggle with the nagging itch to get back on that field. However, I’ve come to the conclusion that if I truly want to push my disc golf limits, I need to fully commit my mind, body, and time to it instead of spreading myself thin.

I don’t think I ever intended for disc golf to replace ultimate completely; it simply began as a way to pass the time during a national shutdown and pandemic. In the short time I’ve played this new sport, however, I’ve quickly come to the realization that it offers much bigger returns than ultimate in the immediate and long-term future. Disc golf is much more accessible than ultimate, and you can significantly improve every day for free. Disc golf is much easier on the body than ultimate as well, and I can play it competitively for much longer. Disc golf demands a higher degree of control over your discs, as the margin for error is many times smaller. Disc golf offers a significantly higher economic ceiling than ultimate does; I’ve made more money playing disc golf in the first two months of 2022 than in my entire ultimate career. And lastly, I’ve found that disc golf requires a higher level of mental focus and fortitude, as every shot comes down to no one else but you.

Ultimate will forever have a place in my heart, along with the people that helped make the sport so special to me. From the friends at Stanford and Johns Hopkins to the friends in Colombia to the friends in Color of Ultimate to the friends in the Dallas Ultimate Community and beyond, I am eternally grateful for every memory, relationship, and experience that I shared with you all.

If there’s one piece of advice I can give to the younger generations of ultimate players, it would be to do everything you can to hold your governing bodies accountable. There’s no reason why USAU, the AUDL, PUL, and WUL can’t work together to create a more cohesive pipeline of accessible ultimate to its players. Quite frankly, it feels like the biggest thing holding some of these organizations back from doing so is that their higher-ups don’t like each other or won’t work together. Once upon a time, I was passionate about helping bridge some of these gaps, but my time has passed and I present this challenge to anyone that feels compelled to help usher in a new era for the structure of ultimate.

As I close, it’s worth noting that the past few weeks have been incredibly nostalgic, and I hope you find value in my reflection on my short career in ultimate. 18-year old Gabe had no idea what he was getting into, but I’m glad he chose to stick it out.