How to avoid shoulder injuries, and what to do if they happen.

February 15, 2022 by Ian Engler in Opinion with 0 comments

Tuesday Tips are presented by Spin Ultimate; all opinions are those of the author. Please support the brands that make Ultiworld possible and shop at Spin Ultimate! Part 1 of this two-part series offers information about the science behind ACL injury prevention.

Shoulder instability is common in ultimate – likely more common than in any other non-contact sport – mostly due to the frequency of laying out, as well as the sudden maximal range of motion that can occur during a catch or going for a block. Ultimate players should know about shoulder dislocations because they may happen to you or a teammate, and it’s useful to know how to help in the moment and as the player thinks about taking care of the injury long term, given the risk of it happening again. In this article, I’ll sum up what ultimate players should know about the topic.

Anatomy

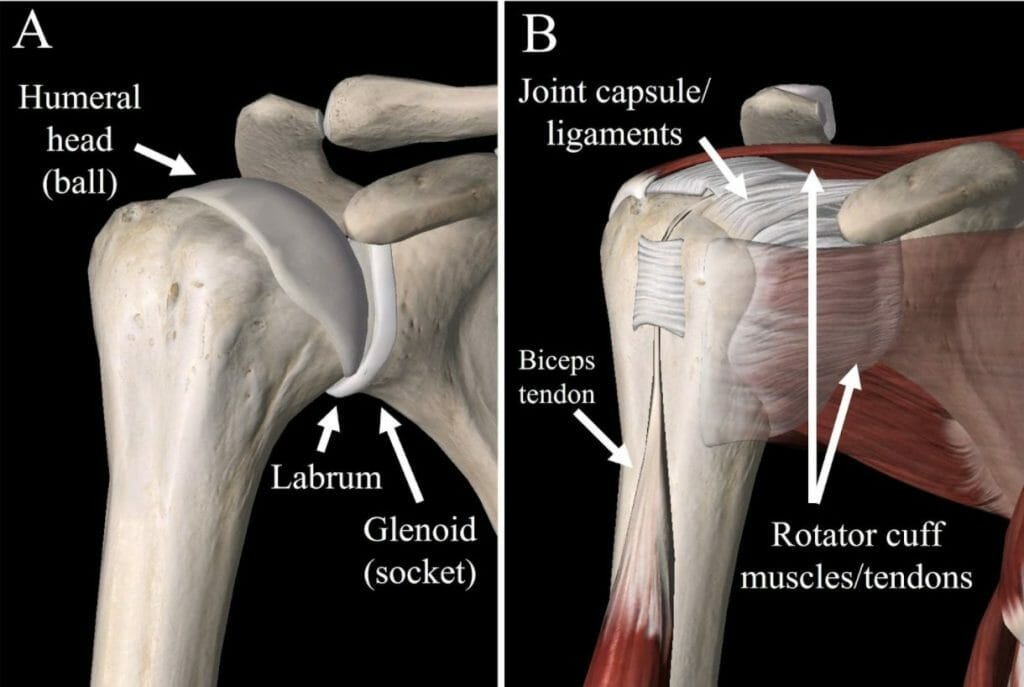

Understanding shoulder anatomy is key to understanding the joint’s instability. The shoulder is a ball-and-socket joint that includes the humeral head (the ball) and the glenoid (the socket).

Unlike in the hip, where the socket is very deep and provides a lot of bony stability, the glenoid is quite flat, making the joint more like a golf ball on a golf tee. The benefit is incredible range of motion, but the downside is that there is less inherent stability to the shoulder. Without the bones providing much stability, the shoulder relies on soft tissues for stability – the labrum (a ring of tissue around the glenoid that effectively deepens the socket), joint capsule with its associated ligaments, and muscles (the rotator cuff and deltoid).

Of note, the AC joint (the bump on the top of your shoulder) is outside of the shoulder joint and can be injured in what’s called a “separated shoulder.” That is very different from a dislocated shoulder and is usually not a problem once the pain dissipates.

Basics of Shoulder Instability

Shoulder instability includes dislocations (i.e., the ball comes completely out of the socket) and subluxations (i.e., the ball comes partially out of the socket but immediately shifts back into place). In a dislocation, the shoulder usually stays out of place for a few seconds to minutes and needs to be put back in place by the athlete or by another person. Shoulders can dislocate anteriorly (out the front) or posteriorly (out the back). Anterior dislocations are much more common and occur when there is a force on the shoulder while it is in an abducted, externally rotated position – essentially the position of a high five (Figure 2). Naturally, the shoulder often gets into this position on layouts or when reaching for a disc overhead and out to the side.

Of course, we do these actions all the time without dislocating our shoulders. A first-time dislocation requires some extra force. That could come from a player laying out and landing mostly on the arm instead of taking the force with their chest, or they may be hit in the arm while they’re reaching outwards and upwards. A shoulder dislocation causes some degree of injury in the shoulder — usually a tear of the labrum, and possibly a small break/fracture in the bone. This injury to the stabilizing structures makes further dislocations more likely.

Preventing Shoulder Dislocations

Across the population, the people most at risk for shoulder instability are younger, male, contact or overhead sports athletes, and those who are ligamentously lax (i.e., their joints hyperextend compared to the average person). Ultimate players fit in multiple of these categories, and, particularly those who lay out a lot, would benefit from taking preventative measures to avoid shoulder injuries.

Injury prevention details could fill another article. The two key components are layout form and shoulder strength. Proper layout form involves taking as much force as possible on the chest/torso and less on the arms. Landing flat without twisting will avoid impacting the shoulders. Strengthening the shoulder muscles, especially the rotator cuff and deltoid, can help prevent shoulder dislocations because the shoulder relies upon muscles for stability. External and, especially, internal shoulder rotation exercises, as well as forward elevation (raising in front of your body), are the most targeted to the relevant muscles.

On-Field Treatment

When someone dislocates their shoulder, they most always know it by feeling the ball out of the socket. A goal is to quickly get the shoulder back in (“reduce the shoulder”) both to prevent continued stretch injury and to decrease pain. An athletic trainer or doctor is certainly best to reduce the shoulder. If none are nearby, the benefits of fast reduction are worth a gentle attempt by a coach or teammate if both people consent. There is low risk of further injury with only gentle use of force. If there is any concern for a fracture (break), largely from the athlete being in especially severe pain, then err on the side of leaving reduction to medical professionals and go to the emergency room.

There are many techniques to reduce the shoulder. A simple technique involves the provider gently straightening the arm down the side of the body with the palm forwards and then gently raising the straight arm in front of the body until just overhead (Figure 3). The shoulder will often reduce. If not, the arm can then be brought into the ‘high five’ position (Figure 2). Alternatively, the provider can help the person to their feet by pulling on the affected hand, which may be enough traction to put the shoulder back in. If these do not reduce the shoulder, the player should go to the emergency room for reduction of the shoulder.

Recovery from a Shoulder Dislocation

If a player dislocates their shoulder for the first time, they should be out of sports until the pain has resolved and the strength and range of motion have returned. Historically, it was recommended to be in a sling for over a week, but literature now shows that a sling for just a few days to a week is best before working on restoring range of motion early and then restoring strength (Paterson 2010). Physical therapy with a PT is best for this. Players most always return to a full level of activity, but with the added risk of reinjury.

Long-Term Treatment and Considering Surgery

There are two options for long-term treatment: no surgery (‘nonoperative’) or surgery. The problem with a shoulder dislocation is that there is a risk of it happening again and again, especially in a high-risk sport like ultimate, so the goal of treatment is to prevent recurrence.

Do further shoulder dislocations matter? Yes –- every dislocation causes some degree of injury, and that means future dislocations are even more likely. Multiple dislocations makes later surgery less successful and more complex and probably increases the risk of arthritis (Rugg 2018, Marshall 2017). Nevertheless, there are many very functional shoulders out there that have gone through a dislocation or two.

Nonoperative treatment involves physical therapy to maximally strengthen the shoulder. The shoulder should be kept strong with exercises for as long as the athlete is playing ultimate, and they should consider laying out less or not at all. This was the main recommended treatment in the past for a first-time shoulder dislocation. Newer studies, though, show up to a 75% re-dislocation rate without surgery, and perhaps higher in younger athletes in high risk sports (Provencher 2021).

Surgery, which usually is an arthroscopic (2-4 small incisions around the shoulder) repair of the labrum and capsule, no doubt decreases the risk of re-dislocation dramatically. Studies show that, compared to no surgery, it brings the risk of redislocation down from 67% to 10% and increases rates of return to sport from 81% to 93% (Hurley 2020). Yet surgery generally requires 4-6 weeks in a sling, with strengthening beginning around three months and return to play around 5-6 months.1 Of note, surgery is highly recommended if an MRI shows a more severe injury to the shoulder than normal (e.g., a fracture/break of the bone).

The best approach after any dislocation is discussion with a doctor weighing the risks and benefits of surgery – how much the athlete wants to avoid dislocation versus avoid the rehabilitation process, where in the season they are, at how high of a level they want to continue to play ultimate, and whether they would give up laying out. There are certainly athletes with one or two dislocations who play ultimate at a high level without issue. This shows why trying nonoperative management is reasonable if the athlete is willing to commit to dedicated strengthening of their shoulder and understands the high risk of recurrence. After 2-3 or more dislocations, though, the athlete should even more strongly consider surgery if they wish to continue ultimate due to the increasing injury and recurrence risk.

Conclusions

Shoulder instability is common in ultimate, and most college or club teams will have one or more players with a shoulder dislocation. Proper layout form and shoulder strength are keys to prevention. Given the risk of reinjury, players should take the injury seriously and seek medical advice. There is often no obvious answer as to choosing surgery or no surgery in a first-time dislocation, so conversations with an orthopedic surgeon or sports medicine doctor on the risks and benefits are very helpful to learn more and make an informed decision about the best way to take care of the athlete’s shoulder.

References

Hurley ET, Manjunath AK, Bloom DA, Pauzenberger L, Mullett H, Alaia MJ, Strauss EJ. Arthroscopic Bankart repair versus conservative management for first-time traumatic anterior shoulder instability: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arthroscopy: The Journal of Arthroscopic & Related Surgery. 2020 Sep 1;36(9):2526-32.

Marshall T, Vega J, Siqueira M, Cagle R, Gelber JD, Saluan P. Outcomes after arthroscopic Bankart repair: patients with first-time versus recurrent dislocations. The American journal of sports medicine. 2017 Jul;45(8):1776-82.

Paterson WH, Throckmorton TW, Koester M, Azar FM, Kuhn JE. Position and duration of immobilization after primary anterior shoulder dislocation: a systematic review and meta-analysis of the literature. JBJS. 2010 Dec 15;92(18):2924-33.

Provencher MT, Midtgaard KS, Owens BD, Tokish JM. Diagnosis and management of traumatic anterior shoulder instability. JAAOS-Journal of the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. 2021 Jan 15;29(2):e51-61.

Rugg CM, Hettrich CM, Ortiz S, Wolf BR, Baumgarten KM, Bishop JY, Bollier MJ, Bravman JT, Brophy R, Carpenter J, Cox CL. Surgical stabilization for first-time shoulder dislocators: a multicenter analysis. Journal of shoulder and elbow surgery. 2018 Apr 1;27(4):674-85.

Surgeons’ exact protocols will vary by surgeon and patient. ↩